The Japanese Occupation Money of 1941-1945

|

Several sections updated - see below (September 2016)

|

Introduction

Often referred to as 'Japanese Invasion Money' or 'JIM', this was a form of currency issued generally from 1942 by the Japanese military authorities as they occupied successive nations across South East Asia, and were intended to be used by the civilian populations to replace all local or other forms of currency. They were officially known as Southern Development Banknotes (at least by 1943). The Bank of Japan refers to the 'Japanese Government' headed notes as the 'Military' notes of the Pacific War. There is some indication that these notes may have been introduced in some areas as early as January 1941. There were different issues of JIM for seven regions: Burma, Malaya, Netherlands-Indies (Indonesia/Shonan), Oceania, and The Philippines, plus an un-issued series for eastern Russia. Japanese occupational issues in other areas are not usually considered part of the series as they were issued outside of the Southern Development Bank system: those of China, French-Indochina and Thailand. Also, the currency issued specifically for military use (mostly adapted Bank of Japan notes), and which mainly circulated within China, are not JIM notes. That said - an argument could be made for including the c1940 issues for China which have a seven character title omitting mention of the military (for example Krause China P M20) could be argued to belong within the series, sharing most of the features common to the JIM notes.

In August 1940, Japanese Prime Minister Matsuoka Yôsuke announced the idea of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a group of Asian nations led by the Japanese and free of Western powers; an "Asia for Asians". As Japan occupied various Asian countries, they set up 'puppet' governments with local leaders who proclaimed independence from the Western powers, and as a powerful addition to this process, created this currency so as to further separate the local peoples from their defeated or exiled governments and the outside world.

The Japanese War Ministry made initial requests for military notes for certain unspecified areas as early as January 16, 1941. On April 1 of that year the Cabinet Printing Office was ordered to produce the first notes for the Dutch East Indies and Malaya.

The earliest issues of JIM were printed in Japan and came into their intended countries of circulation via the invading Japanese soldiers. Later issues seem to have been printed more locally - the manufacture undertaken by printers usually within the country of issue. The notes have certain common traits - all were un-backed by reserves, produced to a poor standard, and do not carry any banking officials signatures or seals. All notes except the 1944 'Dai Nippon' series of the Netherlands Indies (S) bare the small circular seal of the Japanese Ministry of Finance. It is likely that some of this and the related puppet currencies were printed by the Hong Kong works of the Chung Hwa Book Company, as after the defeat of Japan, vast quantities of such notes were discovered in storage at the printers.

In February 1942 Japan passed laws which established the Wartime Finance Bank and later in April of that year, the Southern Development Bank. Both of these banks issued bonds to raise funding for the war. The former loaned money primarily to military industries, whereas the latter provided financial services in areas occupied by the Japanese military, and issued many of these banknotes. Initially these occupation banknotes were primarily issued by the Yokohama Specie Bank (the largest shareholder of which was noneother than the Emperor Hirohito, with 22%), and later the Southern Development Bank additionally took up issue. In the Philippines however the primary issuer of this currency seems to have been the Bank of Taiwan. As can be seen, the notes were not as such backed by any of these banks or other reserve of any kind, being issued in the name of the Japanese Government, and most of the notes do not even bare a 'promise to pay'. Oceania issues were assumedly primarily introduced and kept in circulation by military authority.

The serial numbers and block letters: on most JIM notes the latter are the most commonly encountered. The first letter indicates the country or region of issue: such as B for Burma, M for Malaya, S for (Sumatra or 'Shonan' a name meaning 'Great Eastern Territories' a Japanese term) the Netherlands Indies, O for Oceania and P for the Philippines. The second letter simply indicated the series and ran through in a sequence of batches. On some notes, at the end of a sequence such as PZ, the next block would have the second letter begin from A again, but with the addition of a third letter; as PAA. This would continue through to PAZ, and then on to PBA, and so on. Some letters have yet to appear for reasons unknown but it is most likely that these missing series are due to war action. For instance, there is no known example of series B/AA of the Burma 5 Cents note.

Some of the Philippines JIM currency was unusual for the type in that serial numbers were used as standard on the later pesos notes. For most other JIM notes, the block or serial numbers determine collectors value. Many of the JIM notes are very common and easily obtainable in some cases almost for pennies, however a scarce block or number can vastly raise the value of a note. For example; Malaya or Netherlands Indies notes with full serial numbers are scarcer and can be 20 or 30 times more valuable than the most common block lettered varieties. Burma 1/2 and 1 rupee notes with blocks other than 'BD' are fairly rare.

Across the occupied territories the notes were reluctantly accepted, or imposed by force, and often referred to as Banana notes or Mickey Mouse money.

Often referred to as 'Japanese Invasion Money' or 'JIM', this was a form of currency issued generally from 1942 by the Japanese military authorities as they occupied successive nations across South East Asia, and were intended to be used by the civilian populations to replace all local or other forms of currency. They were officially known as Southern Development Banknotes (at least by 1943). The Bank of Japan refers to the 'Japanese Government' headed notes as the 'Military' notes of the Pacific War. There is some indication that these notes may have been introduced in some areas as early as January 1941. There were different issues of JIM for seven regions: Burma, Malaya, Netherlands-Indies (Indonesia/Shonan), Oceania, and The Philippines, plus an un-issued series for eastern Russia. Japanese occupational issues in other areas are not usually considered part of the series as they were issued outside of the Southern Development Bank system: those of China, French-Indochina and Thailand. Also, the currency issued specifically for military use (mostly adapted Bank of Japan notes), and which mainly circulated within China, are not JIM notes. That said - an argument could be made for including the c1940 issues for China which have a seven character title omitting mention of the military (for example Krause China P M20) could be argued to belong within the series, sharing most of the features common to the JIM notes.

In August 1940, Japanese Prime Minister Matsuoka Yôsuke announced the idea of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a group of Asian nations led by the Japanese and free of Western powers; an "Asia for Asians". As Japan occupied various Asian countries, they set up 'puppet' governments with local leaders who proclaimed independence from the Western powers, and as a powerful addition to this process, created this currency so as to further separate the local peoples from their defeated or exiled governments and the outside world.

The Japanese War Ministry made initial requests for military notes for certain unspecified areas as early as January 16, 1941. On April 1 of that year the Cabinet Printing Office was ordered to produce the first notes for the Dutch East Indies and Malaya.

The earliest issues of JIM were printed in Japan and came into their intended countries of circulation via the invading Japanese soldiers. Later issues seem to have been printed more locally - the manufacture undertaken by printers usually within the country of issue. The notes have certain common traits - all were un-backed by reserves, produced to a poor standard, and do not carry any banking officials signatures or seals. All notes except the 1944 'Dai Nippon' series of the Netherlands Indies (S) bare the small circular seal of the Japanese Ministry of Finance. It is likely that some of this and the related puppet currencies were printed by the Hong Kong works of the Chung Hwa Book Company, as after the defeat of Japan, vast quantities of such notes were discovered in storage at the printers.

In February 1942 Japan passed laws which established the Wartime Finance Bank and later in April of that year, the Southern Development Bank. Both of these banks issued bonds to raise funding for the war. The former loaned money primarily to military industries, whereas the latter provided financial services in areas occupied by the Japanese military, and issued many of these banknotes. Initially these occupation banknotes were primarily issued by the Yokohama Specie Bank (the largest shareholder of which was noneother than the Emperor Hirohito, with 22%), and later the Southern Development Bank additionally took up issue. In the Philippines however the primary issuer of this currency seems to have been the Bank of Taiwan. As can be seen, the notes were not as such backed by any of these banks or other reserve of any kind, being issued in the name of the Japanese Government, and most of the notes do not even bare a 'promise to pay'. Oceania issues were assumedly primarily introduced and kept in circulation by military authority.

The serial numbers and block letters: on most JIM notes the latter are the most commonly encountered. The first letter indicates the country or region of issue: such as B for Burma, M for Malaya, S for (Sumatra or 'Shonan' a name meaning 'Great Eastern Territories' a Japanese term) the Netherlands Indies, O for Oceania and P for the Philippines. The second letter simply indicated the series and ran through in a sequence of batches. On some notes, at the end of a sequence such as PZ, the next block would have the second letter begin from A again, but with the addition of a third letter; as PAA. This would continue through to PAZ, and then on to PBA, and so on. Some letters have yet to appear for reasons unknown but it is most likely that these missing series are due to war action. For instance, there is no known example of series B/AA of the Burma 5 Cents note.

Some of the Philippines JIM currency was unusual for the type in that serial numbers were used as standard on the later pesos notes. For most other JIM notes, the block or serial numbers determine collectors value. Many of the JIM notes are very common and easily obtainable in some cases almost for pennies, however a scarce block or number can vastly raise the value of a note. For example; Malaya or Netherlands Indies notes with full serial numbers are scarcer and can be 20 or 30 times more valuable than the most common block lettered varieties. Burma 1/2 and 1 rupee notes with blocks other than 'BD' are fairly rare.

Across the occupied territories the notes were reluctantly accepted, or imposed by force, and often referred to as Banana notes or Mickey Mouse money.

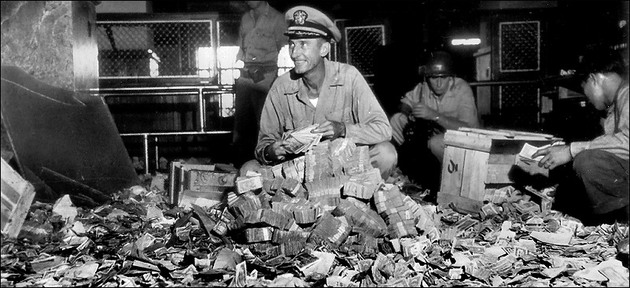

Above: 'Money, Money, money, worthless money, Manila, Philippines, April 10, 1945'. Commander S. J. Wilson looks over a worthless pile of Japanese occupation paper money he found in a building he owned in Manila. The Japanese had operated the building as a bank. (AP Wirephoto, via John T Pilot, Flickr.com)

Clearly, these notes, or scrip, were intended to be only temporary transitional issues as part of Japanese plans to dominate the region, and to minimise or eradicate western influence, in this instance by first replacing all colonial or commonwealth (US) currency issues by these JIM notes, retaining certain familiar features such as the English or Dutch text, and the colonial denominations of dollars, pounds and gulden. Japan was in the process of replacing these with more 'indigenous' issues of currency, utilising national languages, imagery and denominations, when defeat by the allies ended these schemes. Few of these later issues were ever placed into circulation, most survive only as specimen notes, and all are rare. The final aim of the Japanese (at least as summarised in the Kyoto University Economic Review Vol.17, 1942) was to have series of connected currencies across Asia (their Empire or 'Co-Prosperity Sphere') all valued at par with the Bank of Japan Yen: "the yen currencies in Japan, Manchukuo and China are not the same with the currencies proposed or enforced' in the southern region in respect to their monetary objects. However, these two sets of currencies are destined to become unified into a currency system with the deposits with the Bank of Japan as issue reserves for each member of the co-prosperity sphere."

Criticisms are sometimes made of locals who supposedly profited from the Japanese occupation, even of so-called "comfort women" who were usually or always forced into prostitution by the Japanese; that many had made fortunes according to surviving records. The reality however is that over half of the money they did receive, they had to pay to their "owners" and much of the rest had to cover food and other items, which led many of these women into poverty. Further, whatever money they managed to retain became increasingly worthless - as they would have realised - finally worth nothing after the defeat of Japan. (source: fightforjustice.info)

The occupied populations had little choice but to use these notes as alternatives were made unavailable, and such as fees, taxes, rationed items, and admissions could only be paid with these notes. However:

"Scrip was, however, largely, and increasingly, shunned as a store of value. In Malaya, ‘only the most stupid were lulled into a sense of wealth’ by holding large quantities of Japanese notes. Others ‘who had amassed “fortunes” quickly changed the paper money into commodities, and substantial investments’. Apparently, given the opportunity even the clerks in Japanese banks changed their pocket money into British currency."

Criticisms are sometimes made of locals who supposedly profited from the Japanese occupation, even of so-called "comfort women" who were usually or always forced into prostitution by the Japanese; that many had made fortunes according to surviving records. The reality however is that over half of the money they did receive, they had to pay to their "owners" and much of the rest had to cover food and other items, which led many of these women into poverty. Further, whatever money they managed to retain became increasingly worthless - as they would have realised - finally worth nothing after the defeat of Japan. (source: fightforjustice.info)

The occupied populations had little choice but to use these notes as alternatives were made unavailable, and such as fees, taxes, rationed items, and admissions could only be paid with these notes. However:

"Scrip was, however, largely, and increasingly, shunned as a store of value. In Malaya, ‘only the most stupid were lulled into a sense of wealth’ by holding large quantities of Japanese notes. Others ‘who had amassed “fortunes” quickly changed the paper money into commodities, and substantial investments’. Apparently, given the opportunity even the clerks in Japanese banks changed their pocket money into British currency."

Every time there was an Axis defeat, prices rose and the value of the scrip fell further. Successful Allied propaganda campaigns caused additional damage, pointing out that this currency would be rendered completely worthless following the defeat of Japan. The value of the occupation notes fell sharply and rapidly, and as with other currencies of the period, inflationary issues were finally produced to cope with the devaluation, in denominations of 500 and 1000. By this point the money had long since become so worthless that people were using it in blocks, generally of 100 notes, and as such were counted by measuring the thickness of the bundle!

After the war literally millions of these worthless notes were destroyed. A passage in the 'Rothmans Cambridge Collection" booklets states that U.S. combat troops "over-ran the the Treasury depository in the Wilson Building, Manila, which supplied all the occupied territories, and destroyed most of the notes". (above: crates of these notes being bulldozed by US soldiers, probably in the Philippines). Some were retained by those who realised their value as collectors items or simply as souvenirs by servicemen who had fought in the Pacific conflict. Many Philippine issued notes were retained in an unsuccessful attempt to gain compensation from the restored Philippine or defeated Japanese governments. Forgotten stockpiles of JIM notes have regularly appeared ever since, and ironically now, among collectors even the cheapest and most common of these notes is still worth more than it ever was in circulation.

Note regarding watermarks: these are often listed as cloud forms meaning that they appear to be of the stylised cloud formations often seen in Asian art, though this interpretation is incorrect. The forms are of quatrefoil kiri flowers. Some of the same watermarked paper has also been used for issues of the puppet Central Reserve Bank of China.

After the war literally millions of these worthless notes were destroyed. A passage in the 'Rothmans Cambridge Collection" booklets states that U.S. combat troops "over-ran the the Treasury depository in the Wilson Building, Manila, which supplied all the occupied territories, and destroyed most of the notes". (above: crates of these notes being bulldozed by US soldiers, probably in the Philippines). Some were retained by those who realised their value as collectors items or simply as souvenirs by servicemen who had fought in the Pacific conflict. Many Philippine issued notes were retained in an unsuccessful attempt to gain compensation from the restored Philippine or defeated Japanese governments. Forgotten stockpiles of JIM notes have regularly appeared ever since, and ironically now, among collectors even the cheapest and most common of these notes is still worth more than it ever was in circulation.

Note regarding watermarks: these are often listed as cloud forms meaning that they appear to be of the stylised cloud formations often seen in Asian art, though this interpretation is incorrect. The forms are of quatrefoil kiri flowers. Some of the same watermarked paper has also been used for issues of the puppet Central Reserve Bank of China.

|

Both sections updated August 29-31, 2016

|

|

Both sections updated August 11-12, 2016

|

|

Both sections updated September 01-04 2016

|