Shanghai - 上海 |

Updated January 24 2018 |

Section 1: An Introduction to Shanghai

|

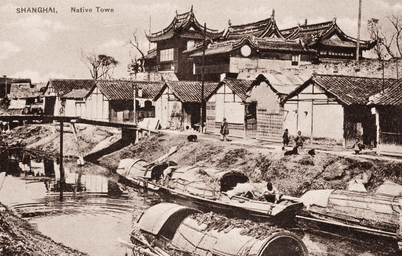

Shanghai is relatively a newcomer - at least when compared with many of China's urban centres. There was only sparse activity in the area until the Song dynasty (960–1126) when Shanghai emerged as a small isolated fishing village, and the current name which means 'Upon-the-Sea', was first in use during this period. The natural advantages of Shanghai as a deepwater port and shipping centre were recognised as coastal and inland shipping expanded rapidly. By the beginning of the 11th century a customs office was established, and by the end of the 13th century Shanghai was designated as a county seat and placed under the jurisdiction of Jiangsu province.

|

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) roughly 70 percent of the cultivated land around Shanghai was given to the production of cotton to feed the city’s cotton and silk-spinning industry. By the middle of the 18th century there were more than 20,000 people employed as cotton spinners.

Following the 1850s the predominantly agricultural focus of the economy was quickly transformed. At this time the city became the major Chinese base for commercial imperialism by Western nations. Following a humiliating defeat by Great Britain in the first Opium War (1839–42), the Chinese surrendered Shanghai and signed the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing), which opened the city to unrestricted foreign trade. The British, French, and Americans were the first to take possession of designated areas - the concessions - in the city, within which they were granted special rights and privileges. The Japanese received a concession in 1895 under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, following their victory in the First Sino-Japanese War.

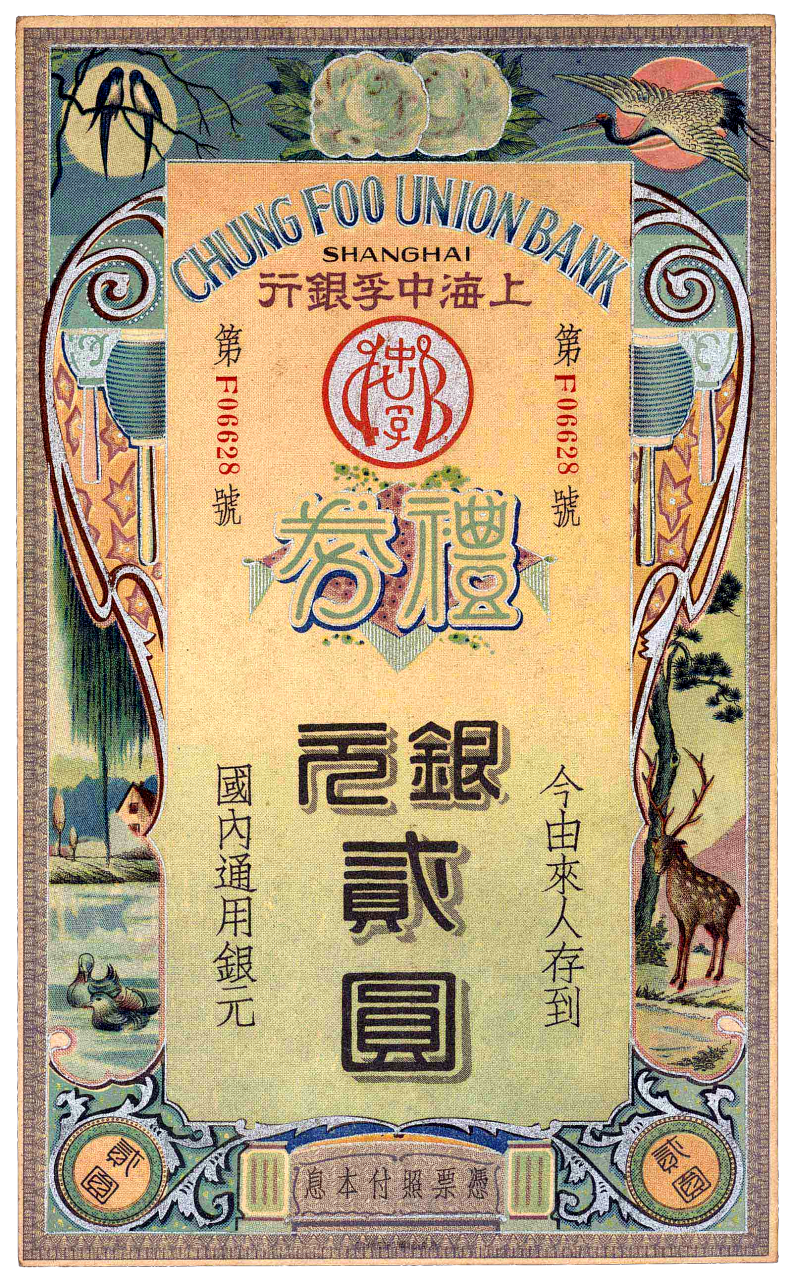

The opening of Shanghai to foreign business immediately led to the establishment of major European banks and multipurpose commercial houses. Shanghai rapidly grew to become China’s leading port and by 1860 accounted for about 25 percent of the total shipping tonnage entering and departing the country. As the flow of foreign capital steadily increased after the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), light industries were established within the foreign concessions, which took advantage of Shanghai’s ample and cheap labour supply, local raw materials, and inexpensive power. Shanghai soon developed to be the city that, then as now, was "a haven for the very rich, and a hell-hole for the poor".

Following the 1850s the predominantly agricultural focus of the economy was quickly transformed. At this time the city became the major Chinese base for commercial imperialism by Western nations. Following a humiliating defeat by Great Britain in the first Opium War (1839–42), the Chinese surrendered Shanghai and signed the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing), which opened the city to unrestricted foreign trade. The British, French, and Americans were the first to take possession of designated areas - the concessions - in the city, within which they were granted special rights and privileges. The Japanese received a concession in 1895 under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, following their victory in the First Sino-Japanese War.

The opening of Shanghai to foreign business immediately led to the establishment of major European banks and multipurpose commercial houses. Shanghai rapidly grew to become China’s leading port and by 1860 accounted for about 25 percent of the total shipping tonnage entering and departing the country. As the flow of foreign capital steadily increased after the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), light industries were established within the foreign concessions, which took advantage of Shanghai’s ample and cheap labour supply, local raw materials, and inexpensive power. Shanghai soon developed to be the city that, then as now, was "a haven for the very rich, and a hell-hole for the poor".

|

The Shanghai International Settlement 上海公共租界

The Shanghai Municipal Council was developed in 1854 in an agreement between the British, French, and US governments after China surrendered it's nominal sovereignty over the Shanghai concessions. In 1863 the British and US concessions were combined to form the International Settlement, with the concessions of other nations becoming involved subsequently. Britain had the most influence, with the most council seats, and control of all but one of the departments. |

|

Above: the flag of the Shanghai International Settlement with shields incorporating the national flags of the principle nations involved.

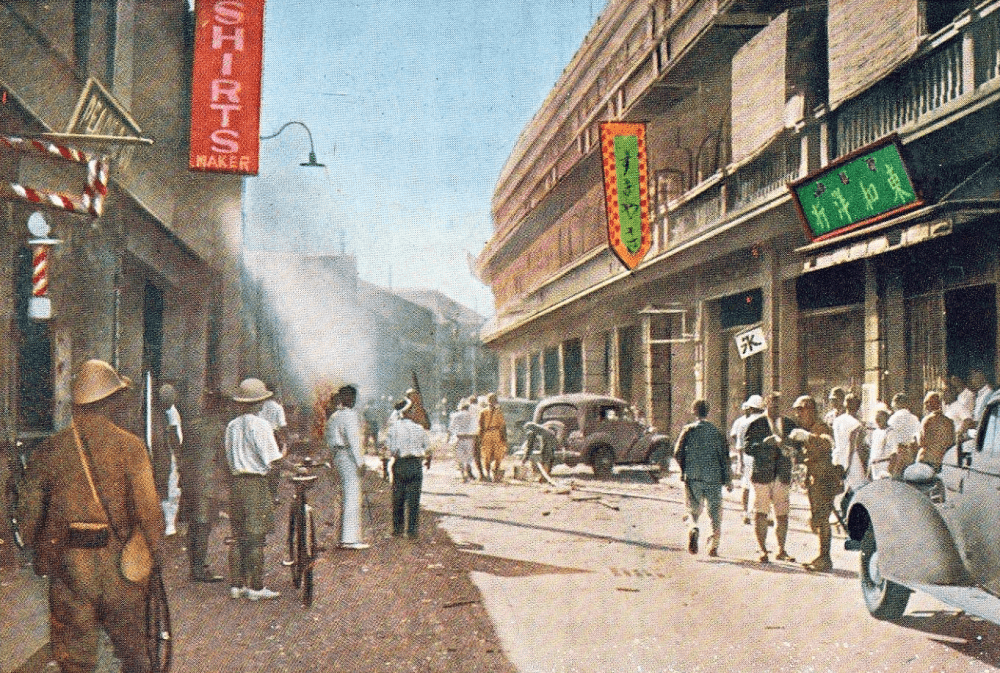

The adjacent French Concession was not part of the International Settlement and was governed by it's own administration. This was abolished in 1943 when the French Vichy Government handed the concession to the control of the Japanese puppet government at Nanking. Following the war, the legitimate government of France confirmed this move in a treaty with Chiang Kaishek's government. Right: unidentified street within the French Concession in 1939. |

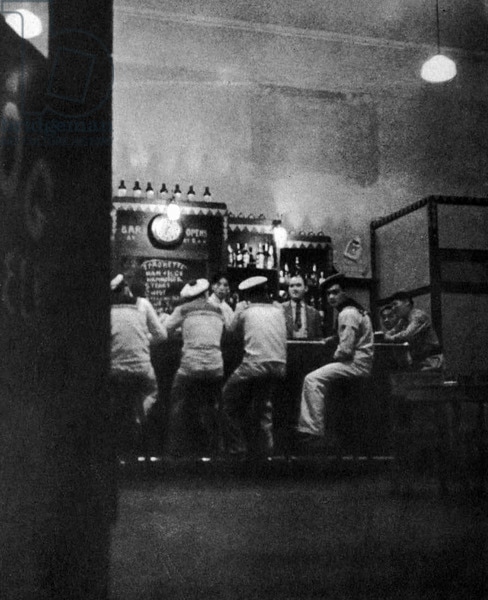

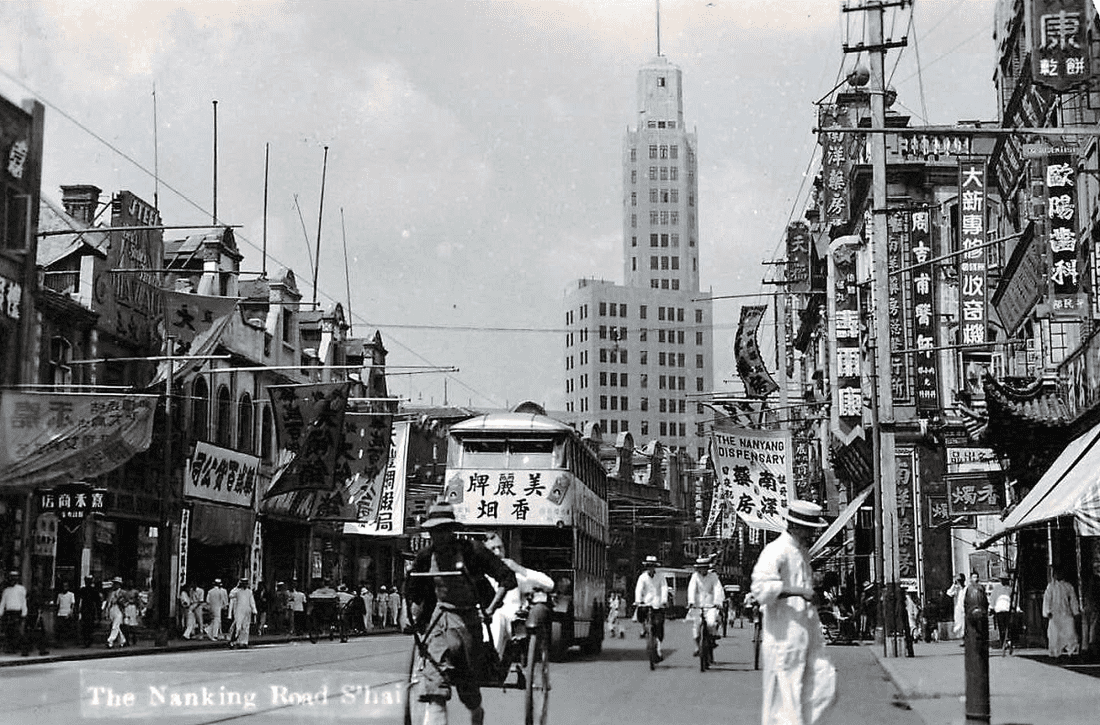

Above (left) Western sailors in a bar on Rue Chu Pao San in 1935, (right) a throng of advertising billboards on Nanking Rd, 1947.

"Sin City", Blood Alley and the Frisco Cafe, 31 Edward VII Avenue

|

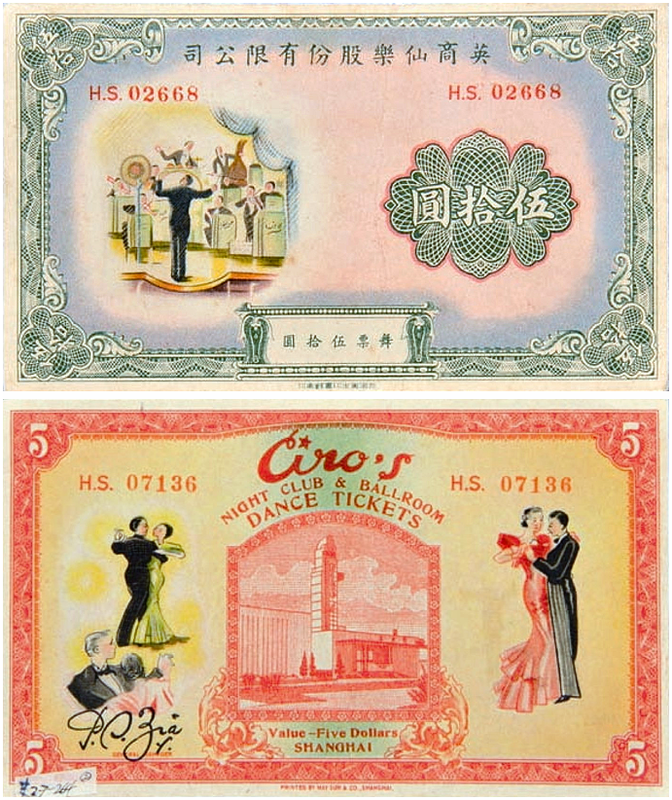

Shanghai had no shortage of dance halls, cinemas and brothels, and was dominated by a trio of powerful 'crime-lords'. The city was said to have had around 100,000 prostitutes; an exaggeration (possibly), but the city drew in many people from far beyond China who often found themselves with few alternative means of financial support. For example, there were thought to be around 8000 White Russian sex-workers operating in Shanghai by 1930.

Almost anything in the way of goods, entertainments and services could be found in Shanghai - to the well-off at least. As the author Christopher Isherwood wrote in 1939: "You can buy an electric razor, or a French dinner, or a well-cut suit. You can dance at the Tower Restaurant on the roof of the Cathay Hotel, and gossip with Freddie Kaufmann, its charming manager, about the European aristocracy of pre-Hitler Berlin. You can attend race-meetings, baseball games, football matches. You can see the latest American films. If you want girls, or boys, you can have them, at all prices, in the bathhouses and the brothels. If you want opium you can smoke it in the best company, served on a tray, like afternoon tea. Good wine is difficult to obtain in this climate, but there is enough whisky and gin to float a fleet of battleships. The jeweller and the antique-dealer await your orders, and their charges will make you imagine yourself back on Fifth Avenue or Bond Street. Finally, if you ever repent, there are churches and chapels of all denominations" An aspect of old Shanghai which is often overlooked is that the city had an active homosexual scene. Ironically - despite some thwarted attempts by the Republican Nationalists - China's long tradition (overall) of tolerance didn't come to an end until sometime after the revolution of 1949: "Male prostitutes were available in the bars and brothels, and in bathhouses where erotic massage was an optional extra. However it would be a mistake to view this as something separate from the heterosexual sex scene; homosexual activity was simply another option for the sex consumer. In the dance halls and night-clubs where partners could be hired to dance, both female and transsexual dancers were available. Courtney Archer writes of this era: Men, and I am not going to call them "gay," would find their pleasures in a personal way with say students, soldiers, actors and servants as would the few Europeans. Because there was no stigma attached there was no need for gay clubs as known in the Western world .. . . As a last resort there were male prostitutes and male brothels in the larger towns. On many occasions in Shanghai when accosted by pimps offering "nice girls" a refusal always brought forth an offer of a "nice boy." This often at 2 p.m. in the middle of a Shanghai summer when one was on the way home for lunch". Bloody Alley The Frisco Cafe was one of the many establishments of the famous (or infamous) 'Blood Alley' (Rue Chu Paosan). The Frisco was especially popular with Americans, and was labelled the "most notorious" of the cabarets by the China Monthly Review in 1938. To read and see more, see the Shanghai section subarticle: 'Blood Alley and the Frisco Cafe, 31 Edward VII Avenue' |

Above: the stage at the Paramount, Shanghai's largest dance hall.

Above: The Canidrome Ballroom, a large Shanghai dance hall in the French Concession.

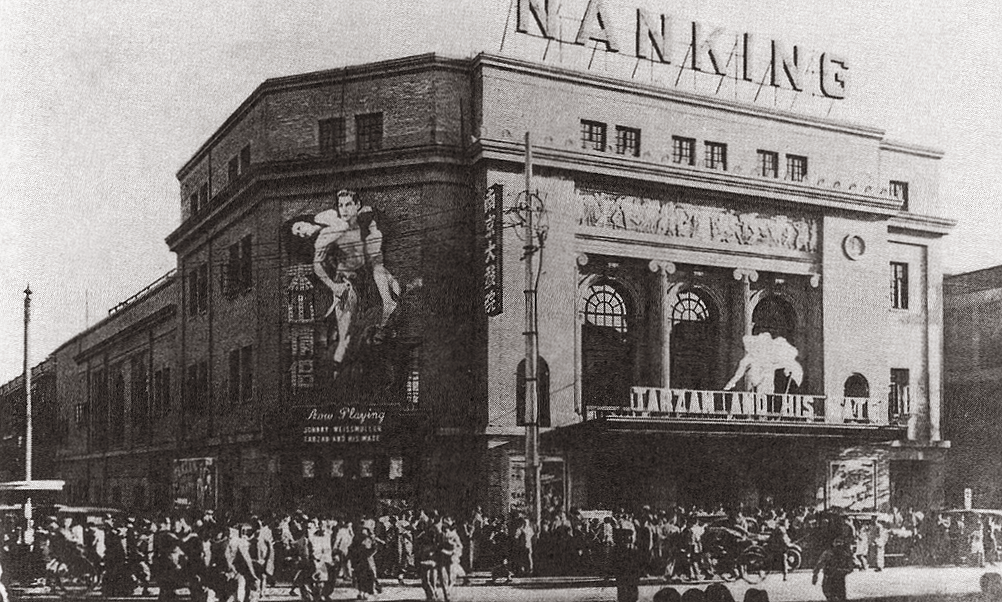

Above: The Nanking Theatre, with advertising for the 1934 US film 'Tarzan and his Mate'.

|

The International Setlement came to a swift end in December 1941; the settlement had remained an island of independence in what was by then a Japanese occupied region controlled by their puppet government at Nanking (Nanjing) for several years. Japanese troops stormed in immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor. In 1943, with Shanghai still occupied by the Japanese, Chiang Kaishek's government at the war-time capital at Chungking (Chongqing) formalised new treaties with Britain and the USA (and later France) which forever abolished the concessions.

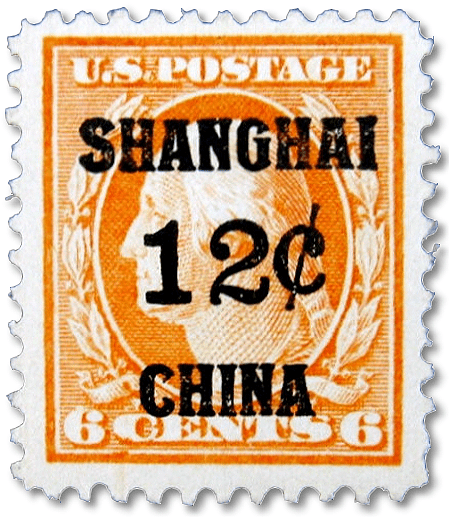

Above: some of the stamps of Shanghai: (left) a red 40 cash local post issue of c1886. (Centre-left) US Postage 6 cents surcharge for Shanghai use at 12 Cents, issued 1919-1922. The US postal agency in Shanghai closed in 1922, as did all other foreign postal agencies. (Centre_right) 5 Cents Shanghai Municipality local post of 1892. (Right) Overprinted French 50c for China, c1900. The French Civilian post office in Shanghai opened in 1862.

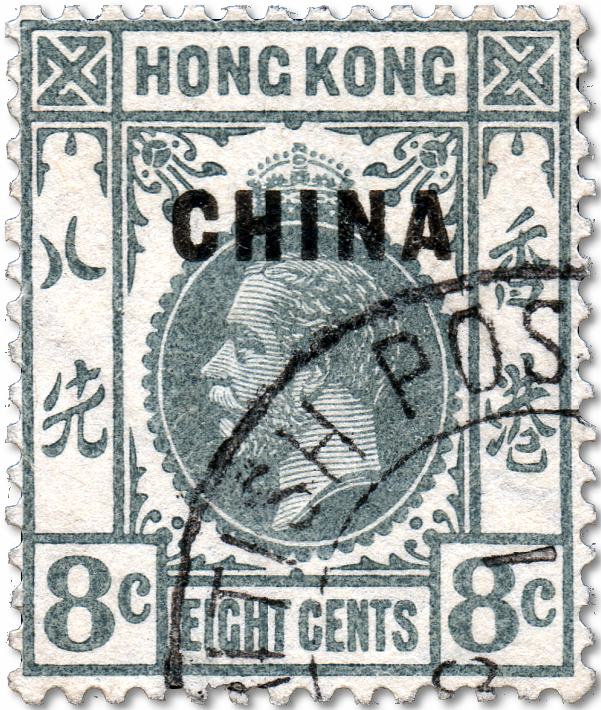

Below: (left) German Post Offices in China, c1906, (centre-left) British Post Offices - Hong Kong 8 Cents, (centre-right) Japanese post offices, Shanghai, 5 Sen c1900, (right) Russian post offices 25 cents surcharge.

Below: (left) German Post Offices in China, c1906, (centre-left) British Post Offices - Hong Kong 8 Cents, (centre-right) Japanese post offices, Shanghai, 5 Sen c1900, (right) Russian post offices 25 cents surcharge.

Local Chinese investment in Shanghai’s industry was minimal until World War I diverted foreign capital from China. From 1914 through the early 1920s, Chinese investors were able to gain a tenuous foothold in the scramble to develop the industrial economy.

The 1920s was also a period of growing political awareness in Shanghai. Members of the working class, students, and intellectuals became increasingly politicized as foreign domination of the city’s economic and political life became ever more oppressive. When the agreements signed by the United Kingdom, the United States, and Japan at the Washington Conference of 1922 failed to satisfy Chinese demands, boycotts of foreign goods were instituted. The Chinese Communist Party was founded in Shanghai in 1921, and four years later the Communist Party led the “May 30” uprising of students and workers. This massive political demonstration was directed against feudalism, capitalism, and official connivance in foreign imperialistic ventures. The student-worker coalition actively supported the Nationalist armies under Chiang Kai-shek, but the coalition and the Communist Party were violently suppressed by the Nationalists in 1927.

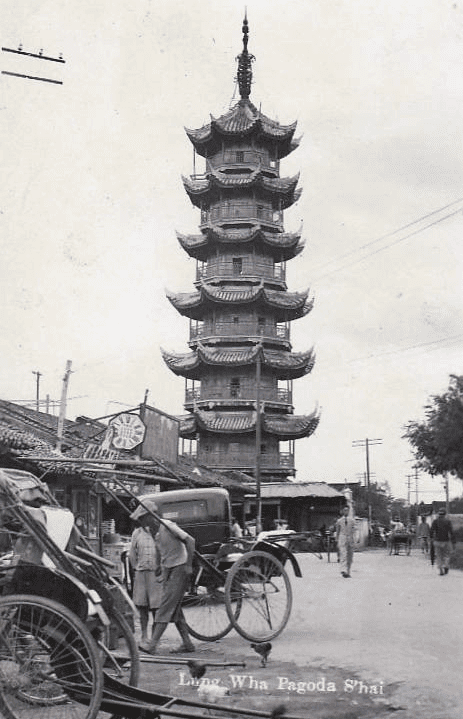

Above: (left) commuters and roadworks on a central Shanghai street in 1931. (centre) The Longhwa Pagoda, (right) The Customs House on the Bund.

|

Shanghai and the Sino-Japanese War

Since 1931, there had been an ongoing and bloody series of conflicts between China and Japan - especially in the vicinity of Shanghai - though no formal declaration of war. Following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 1937, the KMT determined that the "breaking point" of Japanese aggression had been reached. Chiang Kai-shek quickly mobilised the central government's army and air force, placing them under his direct command. The KMT laid siege to the Japanese area of the Shanghai International Settlement, where 30,000 Japanese civilians lived with 30,000 troops, on August 12, 1937. On August 13, 1937, Kuomintang soldiers and warplanes attacked Japanese Marines in Shanghai, leading to the Battle of Shanghai (August–November 1937). On August 14, Kuomintang planes bombed the Shanghai International Settlement, which led to more than 3,000 civilian deaths. In the three days from August 14 through 16, 1937, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) sent many sorties of the then-advanced long-ranged G3M medium-heavy land-based bombers and |

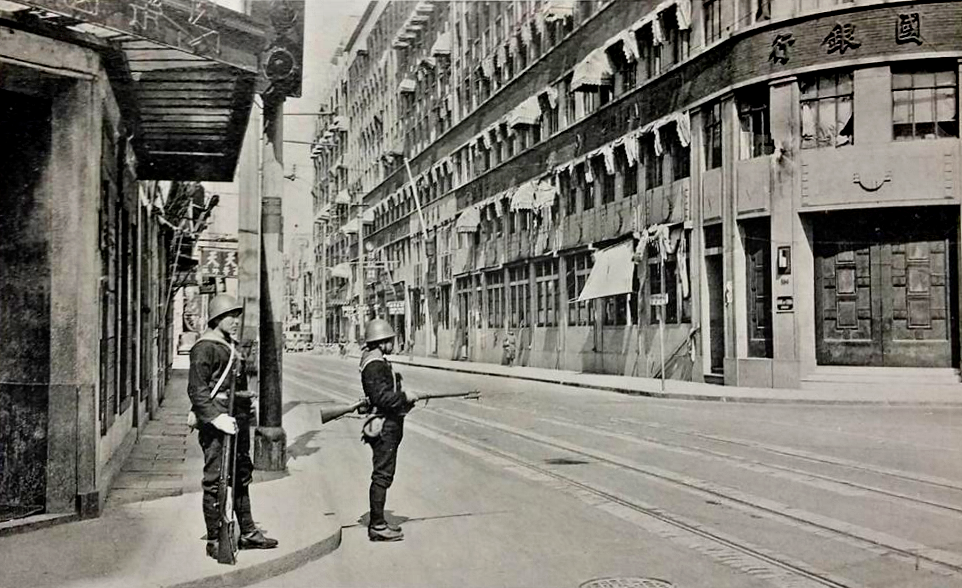

Above: Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces during the Battle of Shanghai, August 1937.

|

assorted carrier-based aircraft with the expectation of destroying the Chinese Air Force, but encountered unexpected resistance from the defending Chinese fighter squadrons; suffering heavy (50%) losses from the defending Chinese pilots.

Three months of fierce fighting commenced, involving nearly 1 million troops; the strength of resistance surprised the Japanese. Nonetheless, Tokyo soon took control of all of the Chinese controlled municipality - with Chinese forces making a fateful retreat towards Nanking - leaving only the International Settlement as an island of independence and nominal Nationalist Chinese control. This too would of course not last. Following the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese forces moved quickly to take control of the remainder of Shanghai (and of Hong Kong).

|

Right: Commercial scrip issued by the Wing On Company Ltd, Shanghai, denominated for $100, c1940. This has been overprinted 'CRB' above each '$100' to show that it was only exchangeable for the currency of the Japanese puppet bank, The Central Reserve Bank of China. Wing On was (and is) a Hong Kong based department store company. The Shanghai branch was opened in 1918 on Nanking Road (today's Nanjing Road), and was at the time one of the "big four" department stores of Shanghai. |

Above: (left) a view along the Nanking Road during the late 1930s. (right) the aftermath of one of many attacks in 1937, during the beginnings of the 1937-1945 Sino-Japanese War.

Refugees in Shanghai

|

Before the arrival of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution and the war in Europe, the International Settlement and French Concession were home to two main Jewish groups. The older and smaller group consisted of about 700 Sephardic Jews whose fathers and grandfathers had arrived from Iraq as traders in the mid-1800s. The second and larger community comprised a few thousand Ashkenazi Jews who had fled to China as refugees from Russia during the Revolution of 1917. Most of them earned modest livings as small business owners. An estimated 17,000 German and Austrian Jews first trickled into Shanghai after the beginning of Nazi persecution of Jews in 1933, and then, following the 1938 violence of Kristallnacht, streamed in. These early refugees usually immigrated to Shanghai as families. Stripped of most of their assets before fleeing the Reich, these thousands of refugees swarmed into Hongkew because they could not afford to live anywhere else in the foreign concessions. During the 1930s, Nazi policy encouraged Jewish emigration from Germany, and a ship's passage enabled a person to gain release, even from a concentration camp. At first, Shanghai seemed an unlikely refuge, but as it became clear that most countries in the world were limiting or denying entry to Jews, it became the only available choice. Until August 1939, no visas were required for entering Shanghai. Ernest Heppner, who fled Breslau with his mother in 1939, recalled that the “main thing was to get out of Germany, and really at this point, people did not care where we went, anywhere just to get away from Germany” (Ernest Heppner, USHMM Oral History, 1999). Arrival in Shanghai was a shock, especially for those who had just stepped off a European liner on which they had been served breakfast by uniformed stewards and now found themselves lining up for lunch in a soup kitchen. Once the refugees settled in, finding work was a challenge, and many refugees had to rely on at least some charitable relief. Understandably, a few of the refugees resorted to such as counterfeiting, as surviving court records of the time reveal - resulting (most likely) in such as the fascinating lithographed counterfeit of the 1914 5 Yuan of the Bank of Communications, as found in the fakes and forgeries section. |

Above and below: Jewish refugees arriving in Shanghai, c1940.

|

|

Above: a Jewish restaurant in the Hongkew quarter of Shanghai, c1930s.

|

Still, the majority of German and Austrian Jews managed. Despite the blows to Shanghai's economy dealt by the Sino-Japanese conflict, some of them adapted well, taking advantage of opportunities that the city offered. The Eisfelder family, who arrived at the end of 1938, opened and operated Café Louis, a popular gathering place for refugees throughout the war years. Others established small factories or cottage industries, set themselves up as doctors or teachers, or worked as architects or builders to transform sections of bombed-out Hongkew. By 1940, an area around Chusan Road was known as “Little Vienna,” owing to its European-style cafés, delicatessens, nightclubs, shops, and bakeries. When Shanghai's refugee population suddenly jumped from about 1,500 at the end of 1938 to nearly 17,000 one year later, the local Jews were overwhelmed and hard pressed to find the resources to help needy families. The Committee for Assistance of European Jewish Refugees in Shanghai, formed in 1938 by prominent local Jews, turned to the Joint Distribution Committee in New York for additional funds. The JDC appropriation rose from $5,000 in 1938 to $100,000 in 1939. Even this barely kept up with the mounting demands. By late 1939, more than half of the refugee population required financial help for food or housing. The Committee for Assistance established five group shelters for a minority of totally impoverished German and Austrian Jews. These shelters were called Heime (“homes” in German). The Ward Road Heim that opened in January 1939 was hastily converted from a former |

barracks and outfitted with hard, narrow bunk beds under which the residents stored their few belongings. By the end of 1939, about 2,500 people lived in the Heime, sleeping anywhere from six to 150 to a room. An additional 4,500 individuals ate in soup kitchens set up in the Heime but lived elsewhere in rented rooms. Many of them received relief help to pay for all or part of their housing costs.

(adapted from the article: "German And Austrian Refugees in Shanghai", US Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

(adapted from the article: "German And Austrian Refugees in Shanghai", US Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

The End of 'Old Shanghai'

Following the defeat of Japan in 1945, Shanghai returned briefly to being something of it's former self, though without the semi-colonialism of the now abolished International Settlement and the other concessions.

Any peace and unity was short lived, as the Civil War between the Nationalists and the Communists resumed.

|

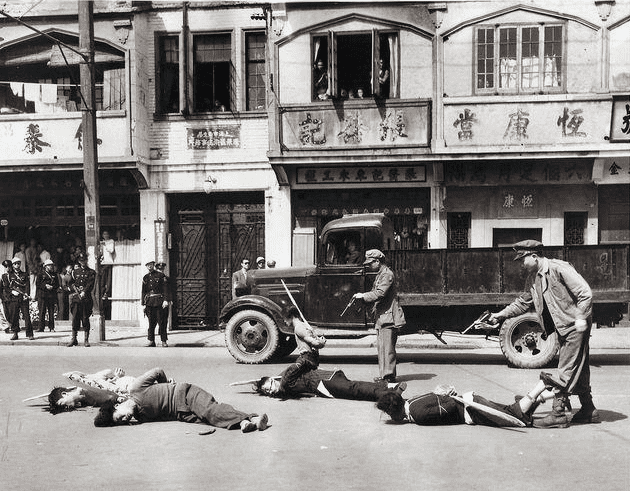

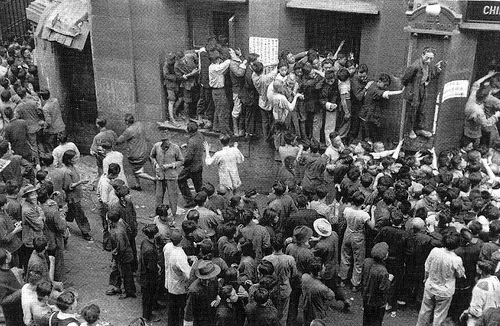

Nationalist policemen executing Communist agents on May 16 1949, shortly before Shanghai fell to communist troops.

|

Communist rally in Shanghai, mid 1960s.

|

|

The Takeover

At the end of May 1949, the Communist forces took control of Shanghai. In the days and weeks leading up to this, many local and foreign residents had fled the city. Most however stayed, and many including some foreign residents welcomed the Communist takeover, viewing the crumbling, corrupt and increasingly authoritarian GMD (KMT) regime with hostility. Many people labelled as communists had been executed by the Nationalists, often in the street, as the Civil War had progressed, culminating in a swath of executions in Shanghai as the Communist Army approached. "It was by no means with complete dismay that Shanghai's foreign community viewed the approach of the Chinese Communists in May 1949. Together with the Chinese population, though in considerably less degree, we had suffered increasingly from maladministration by most of the dominant figures of the Nationalist regime." (Randall Gould, 1949). Left: Shanghai, 1949. A parade celebrating the solemn entry of the army in Shanghai, on August 1st, 1949. A trade union representative holds the enlargement of a banknote of the new currency of the Peoples Bank of China. Photo: Henri Cartier-Bresson |

|

Right: a 1949 Communist issue 3 Yuan stamp showing simple outline maps of Shanghai (left) and Nanking (Nanjing) (right). This was issued by the East China Peoples Post to commemorate the liberation of these two important cities. |

Left: (Henri Cartier-Bresson) Shanghai June 1949 parade celebrating the liberation by Communist forces. The crowds gathered to watch the procession of new tanks and troops. |

|

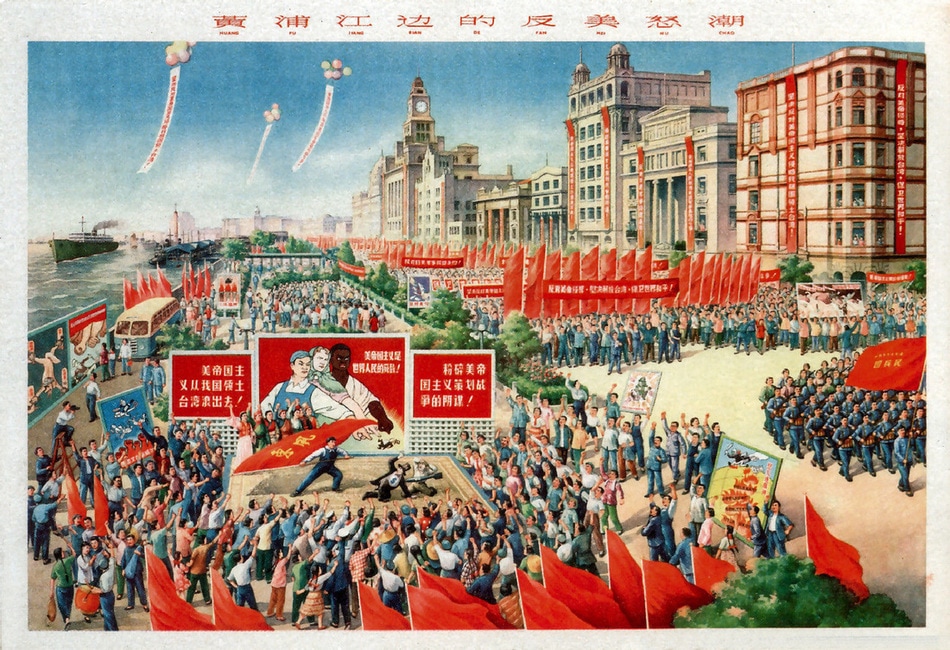

Above: a 1961 propaganda poster by Zhang Yuqing depicting a 'Anti-American wave of rage next to the Huangpu river'. Left, in front; a propaganda play is performed, with an American capitalist and soldier under attack. The billboards and the placards carried in the demonstration are historically correct, just like the buildings of the Bund in the background. The Customs House is clearly visible, with the former HSBC building peaking out beyond it.

|