Blood Alley and the Frisco Cafe, 31 Edward VII Avenue |

Created January 06 2017

|

|

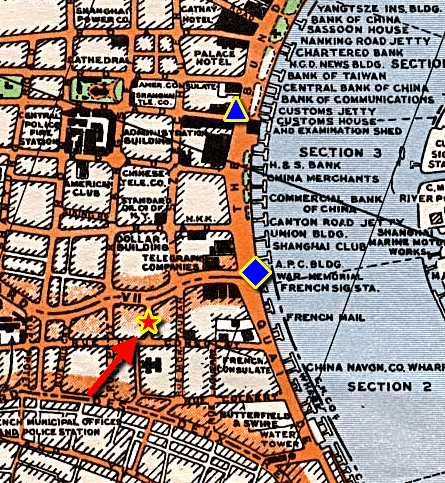

The Frisco Cafe was one of the many establishments of the famous (or infamous) 'Blood Alley', Rue Chu Paosan, on the corner with Avenue Edward VII, within the French Concession. The street was named for the founder of the Commercial Bank of China. The Frisco (and the Ritz opposite) was especially popular with Americans, and was labelled the "most notorious" of the cabarets by the China Monthly Review in 1938. In 'Sin City' by Ralph Shaw (a British journalist resident in Shanghai during 1937-1949) he writes: "Blood Alley, or to give it its proper title, Rue Chu Pao-san, was a short street off Avenue Edward VII - a thoroughfare entirely dedicated to wine, women, song and all-night lechery. The only business of Blood Alley was the easy pickings to be had from the drunks, the sailors, soldiers and cosmopolitan civilians, who lurched there in search of the joys to come from the legion of Chinese, Korean, Annamite, Russian Eurasian, Filipino and Formosan women who worked the district. Here were the Palais Cabaret, the 'Frisco, Mumms, the Crystal, George's Bar, Monk's Brass Rail, the New Ritz and half a dozen others - opened in the case of the cabarets around 6 p.m. daily and closed, depending on the staying power of the customers, any time after 8.30 a.m. the following day. |

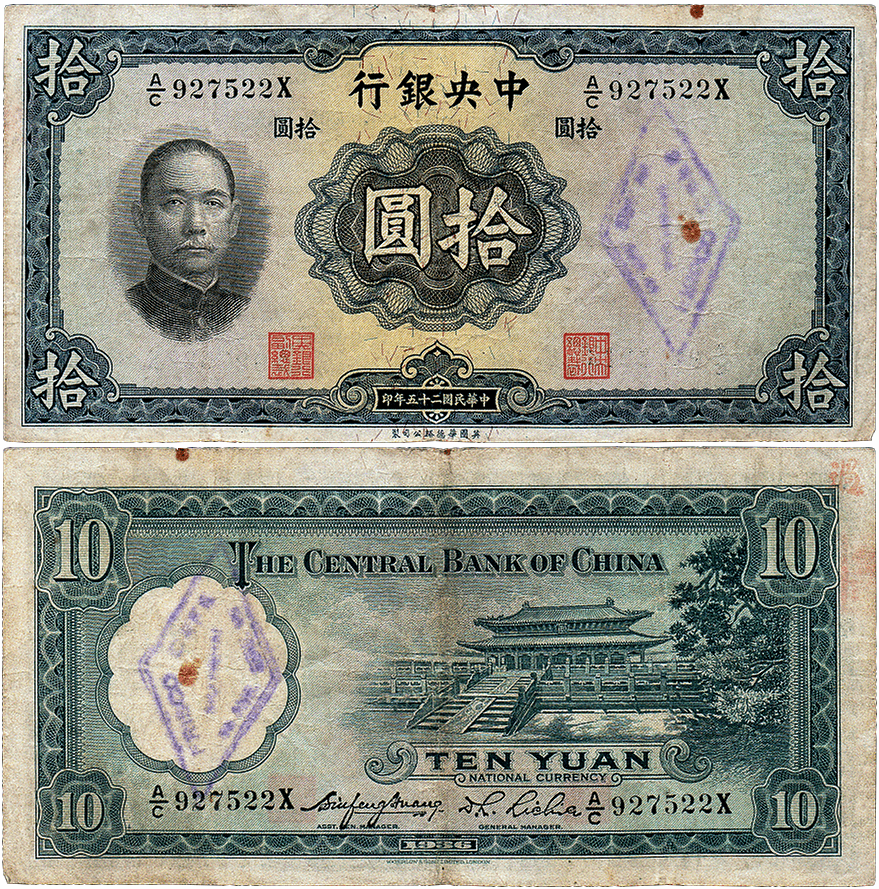

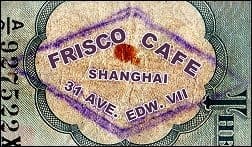

Central Bank of China 10 Yuan of 1936 with an overstamp of the Frisco Cafe, with an enhanced image/reconstruction, lower left

|

|

Rear Admiral Kemp Tolley in his book 'Yangtze Patrol';

"Under the proper stimulus, Marines were never slow in tangling with men of the various other foreign detachments. A very satisfactory state of belligerency could be established by a leading question or a facetious remark concerning a Seaforth Highlander's kilt. A typical sporting event of this nature occurred one day in uptown Shanghai, wherein the American Marines and their British opposite numbers had become enthused over the advent of a payday coupled with a Saturday afternoon, and with more luck than good management found themselves in the same drinking establishment, on their joint border. The result was easily predictable, and soon proved the need of intervention. In the tradition of the Texas Rangers - send only one man for one riot - the Settlement police dispatched two Sikh constables to restore order. These tall, immensely dignified fellows, their beards swept back under their turbans, had a system: Whenever a battler downed his opponent, one or the other of the Sikhs would gently push him in the direction of someone similarly disengaged. In a fairly short time, there were only two combatants left on their feet, both groggy. These, the two Sikhs had no trouble subduing and sending on their way. Not a Sikh whisker been displaced nor a club swung. No knives had flashed, no shots rung out. The Chinese “boys” climbed out from under the tables and from behind the bar. Honors mutually secure, those badly damaged withdrew to lick their wounds. Those in better shape amiably closed ranks and called for beer: “Aye! Thot was a bloody good scrap, Yank. Come and have one on me!" |

|

Above: (upper) Rue Chu-Pao-San during the day, with signs for the Royal, Charleston and Fantasia Cafe-Bars visible. (lower) The entrance to the street from Edward VII Avenue, showing the avenue facing frontage of the Frisco Cafe and Cabaret. A Shanghai Police Special Branch report of November 1936 interestingly lists that an ex-policeman Fred Barling was the the manager of the Frisco. (Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai By Robert Bickers, no page numbers?!)

A final unfortunate/amusing fact is that most of the buildings of Blood Alley were at the time owned by the Catholic Church. The Alley became a shadow of itself after the Japanese occupation, and what remained died off with the Revolution of 1949. Right: a colourful advertising poster typical of the period, this example for selling brandy. The labelling of the bottle shown looks more like that of an absinthe bottle, possibly a deliberate visual association for the by then banned drink. |

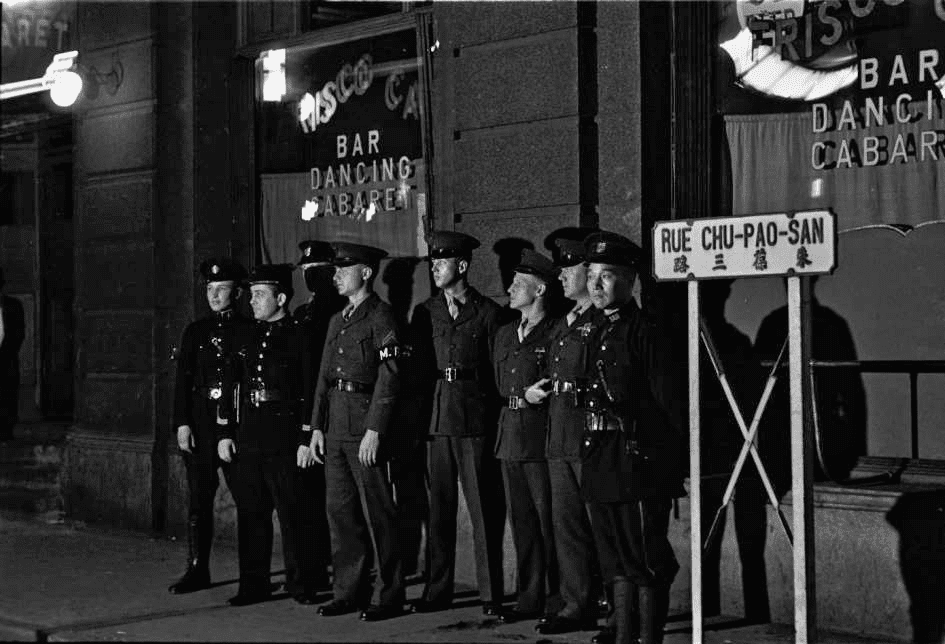

Below: six photos from 1937 showing 'Blood Alley' and some of its patrons.

The two exterior scenes showing the military and police next to the street sign, are taken in front of the Frisco Cafe; the name can be made out on the windows behind them. Blood Alley barmen were generally known to be 'experts' at moving fights out into the street where the civilian and military police could more effectively deal with those involved. The second image down on the left shows two sailors among the military police - presumably arrested by them?

Some or all of the remaining interior scenes may be from inside the Frisco - or in any case one of the venues on that street. (Source: collections of the University of Wisconsin -photos by Harrison Forman).