Old Counterfeits |

Updated December 02 2016

|

Forgeries made during the period of issue of the original note are a fascinating area for collecting and study, and such items are the one type of forgery that in most cases you do want to find in your collection. Such currency is far scarcer and nearly always more valuable now than the original note, at least in the case of commonplace notes.

Both individuals and larger criminal gangs have been forging paper currency since it's introduction, and with varying degrees of success. Some forgeries are very difficult to spot while others are almost laughable in their incompetence, though sometimes even fairly obvious forgeries can be found heavily circulated, with some seemingly never having been identified.

Not all forgeries are the product of straightforward criminal activity. During periods of conflict, a common weapon against an enemy government is to flood their areas of control with fake money to destablise their economy, spreading discontent and therefore weakening their support and control. This tactic was used widely during World War II in Europe and Asia. The Japanese widely counterfeited the issues of the Chinese Nationalist government banks; sometimes using the original printing plates when Shanghai and Hong Kong came under their control. The Norborito Army Laboratory in Japan was responsible for creating and printing many of the forgeries (see below), though unfortunately the detailed records of their activities were destroyed at the time of Japan's surrender in 1945. The Communists are also believed to have forged nationalist currency. The Nationalists in turn greatly forged Japan's money and that of it's 'puppet banks' in occupied regions of China.

The Norborito Army Laboratory in Japan

The wartime currency forgery by the Japanese was on a massive scale with hundreds of millions of yuan in forged notes being transferred to mainland China every month. This was part of Japan's wartime strategy to undermine the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai Shek by disrupting, even ruining the economy. Much of this money was circulated through it's distribution to occupying Japanese troops, and by collaboration with criminal gangs in Shanghai (c. below: 1941 10 yuan, P159a). Some of this currency may have been forged from the original engraving plates as the Dah Tung plant fell under Japanese control in 1941.

The Nationalists in turn developed their own scheme, forging issues of the puppet banks (such as the 1940 5 and 10 yuan of the Central Reserve Bank of China) for similar purposes.

Right: examples of unfinished forgeries of the Bank of Communications 1941 10 yuan (P159a), found at the site of the Norborito Laboratory.

The Japanese forgeries are also thought to include 5 yuan issues (of the Bank of China and Central Bank), the 1940 Bank of China 10 yuan issue depicting Sun Yatsen (the ABNCo note). Also the 1, 5 and 10 yuan notes of the Farmers Bank of China (forged in April 1940). Further the capture of millions of partially completed notes and the forgery itself are most likely the principle reasons for the decision by the Nationalist government at Chungking (Chongqing) to restrict currency issue to the Central Bank of China, from 1942.

An article on the Japanese forgeries:

Both individuals and larger criminal gangs have been forging paper currency since it's introduction, and with varying degrees of success. Some forgeries are very difficult to spot while others are almost laughable in their incompetence, though sometimes even fairly obvious forgeries can be found heavily circulated, with some seemingly never having been identified.

Not all forgeries are the product of straightforward criminal activity. During periods of conflict, a common weapon against an enemy government is to flood their areas of control with fake money to destablise their economy, spreading discontent and therefore weakening their support and control. This tactic was used widely during World War II in Europe and Asia. The Japanese widely counterfeited the issues of the Chinese Nationalist government banks; sometimes using the original printing plates when Shanghai and Hong Kong came under their control. The Norborito Army Laboratory in Japan was responsible for creating and printing many of the forgeries (see below), though unfortunately the detailed records of their activities were destroyed at the time of Japan's surrender in 1945. The Communists are also believed to have forged nationalist currency. The Nationalists in turn greatly forged Japan's money and that of it's 'puppet banks' in occupied regions of China.

The Norborito Army Laboratory in Japan

The wartime currency forgery by the Japanese was on a massive scale with hundreds of millions of yuan in forged notes being transferred to mainland China every month. This was part of Japan's wartime strategy to undermine the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai Shek by disrupting, even ruining the economy. Much of this money was circulated through it's distribution to occupying Japanese troops, and by collaboration with criminal gangs in Shanghai (c. below: 1941 10 yuan, P159a). Some of this currency may have been forged from the original engraving plates as the Dah Tung plant fell under Japanese control in 1941.

The Nationalists in turn developed their own scheme, forging issues of the puppet banks (such as the 1940 5 and 10 yuan of the Central Reserve Bank of China) for similar purposes.

Right: examples of unfinished forgeries of the Bank of Communications 1941 10 yuan (P159a), found at the site of the Norborito Laboratory.

The Japanese forgeries are also thought to include 5 yuan issues (of the Bank of China and Central Bank), the 1940 Bank of China 10 yuan issue depicting Sun Yatsen (the ABNCo note). Also the 1, 5 and 10 yuan notes of the Farmers Bank of China (forged in April 1940). Further the capture of millions of partially completed notes and the forgery itself are most likely the principle reasons for the decision by the Nationalist government at Chungking (Chongqing) to restrict currency issue to the Central Bank of China, from 1942.

An article on the Japanese forgeries:

|

"RESEARCHERS: JAPANESE ARMY USED PRIVATE PAPER MILL TO COUNTERFEIT CHINESE BILLS IN WAR

Posted by Nobuyuki Watanabe, Staff Writer, Asahi Shimbun on 1/27/2015 The Imperial Japanese Army used a private sector company to produce an abundance of counterfeit banknotes that helped to advance Japan’s front lines in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, a recent discovery shows. Researchers at Meiji University studied 279 sheets, each about 30 centimetres square, that were left at Tomoegawa Co.’s paper mill in Shizuoka. They concluded that the sheets were part of the army’s operation to fake banknotes used in the Republic of China during the war. The army’s Noborito institute in Kawasaki had placed an order for the sheets with the Tokyo based company. This suggests the army institute was involved in not only developing biological weapons, balloon bombs, toxins and other confidential defence technology but also in counterfeiting money. The remains of the army institute are now preserved as the university’s Noborito Institute Peace Education Resource Center, which opened in 2010 in Tama Ward. According to the researchers, the sheets showed watermarks of a profile of Sun Yatsen, the Chinese revolutionary and founding father of the Republic of China. They also contain silk fibers. These features are identical to those of a 5 yuan banknote that was widely circulated in the Republic of China at that time. Other sheets found at the mill had watermarks of the Temple of Heaven, a historic structure in Beijing, that appeared on a different kind of 5 yuan bill back then. A former Imperial Japanese Army officer who was in charge of the counterfeiting project wrote in a postwar book that the operation had created fake bills worth 4 billion yuan since its start in 1939. Akira Yamada, professor of modern Japanese history at Meiji University, said it had long been thought that paper for the fake bills was produced only at the army institute because of the highly confidential nature of the operation. “Having a company in the private sector involved in the project made it possible to make a vast volume of banknotes,” said Yamada, who is also head of the Noborito institute. “Japan was able to expand its battle lines in China apparently because it could secure supplies to continue fighting with a wealth of forged banknotes.” The sheets were produced between August 1940 and July 1941, the researchers said, citing the letters printed on them. There were also signs that workers ensured the bills looked authentic by checking the sophistication of the watermarks and the amount of silk fibres used. According to the Noborito institute, authentic banknotes used in the Republic of China were printed in Hong Kong using technology from the United States and Britain. Former employees with the army institute have testified that the machines and original plates to print the bills in Hong Kong were confiscated and taken to the institute after Japan occupied Hong Kong in 1941. Some historians said the army facility was unable to produce as many fake bills as Japan had hoped for. It was located on a hill, making it difficult to secure a steady water supply for the production of the paper. The researchers’ findings came after they sent inquiries to companies that had business dealings with the army institute, which was inaugurated in 1937. Most of the army institute’s facilities and documents were destroyed when Japan was defeated in 1945. |

This article was originally written by Nobuyuki Watanabe and published January 6, 2015 on the Asahi Shimbun website.

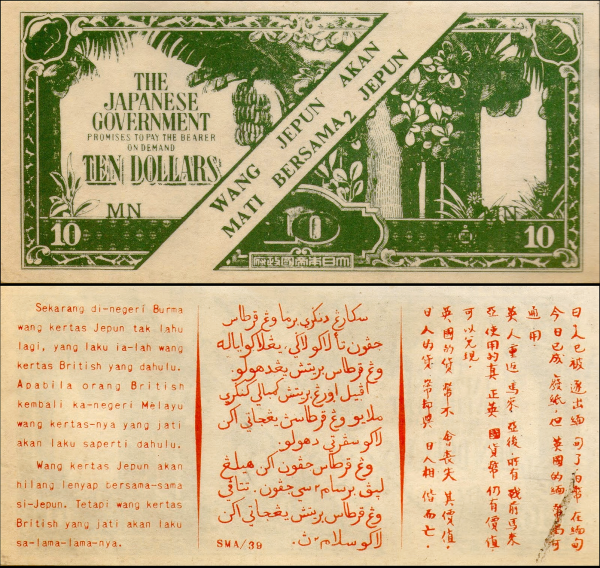

Across Asia

Beyond China, the Allies: namely the US, Britain and Australia were forging the Japanese occupation money for Burma, Malaya, the Philippines, the Netherlands Indies and Oceania. In Australia, in addition to the officially sanctioned counterfeits; one or more small businesses were producing replicas of the Oceania money which held a particular 'morbid' interest at the time due it being denominated in pounds and shillings - it was a common but mistaken belief that this money was for a planned invasion of Australia by Japan.

Beyond China, the Allies: namely the US, Britain and Australia were forging the Japanese occupation money for Burma, Malaya, the Philippines, the Netherlands Indies and Oceania. In Australia, in addition to the officially sanctioned counterfeits; one or more small businesses were producing replicas of the Oceania money which held a particular 'morbid' interest at the time due it being denominated in pounds and shillings - it was a common but mistaken belief that this money was for a planned invasion of Australia by Japan.

Some examples of period forgeries

Chinese forgeries

|

Genuine Bank of China 1 Yuan of 1918. Shanghai branch.

A well worn note and in comparable condition to the forgery example (right). Issued c.1926-27 |

Forgery Bank of China 1 Yuan of 1918. Shanghai branch.

A lithographed forgery of the first issue of this note. The back appears more convincing than the front - the underprint in particular is reproduced poorly - however the note clearly circulated for many years. |

|

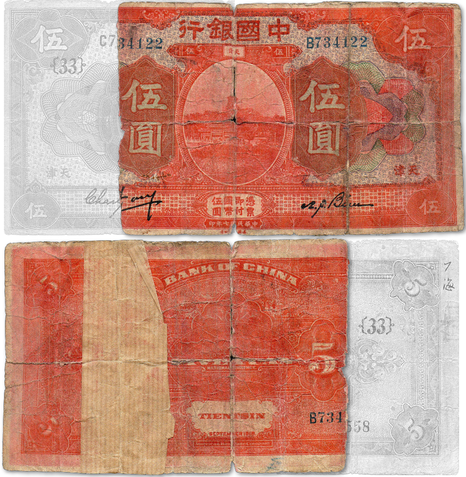

Bank of China 5 Yuan, 1918. Tientsin (Tianjin) branch.

A lithographed forgery with signatures of the 1919-1922 period of issue. The poor condition of this note shows that this fake was likely never detected, and circulated for many years. |

Bank of Communications 5 Yuan of 1914, Shanghai branch.

A lithographed forgery printed on bond paper - when held up to the light a partial watermark of 'bond' can be seen in the margin. The signatures show that this forgery was produced in the late 1930s but is presumably too crude to be associated with the Japanese military counterfeiting of Nationalist notes. Records of the First Special District Court at Shanghai, of 1940, detail a fraud case in which refugees Siegfried Pinkus, Isidor Director and Hans Rechtling were arrested and brought before the court for passing counterfeit $5 bills. The type is not known but it could well be these BoC $5; the forgery was produced during this period. Source: p136: 'Wartime Shanghai and the Jewish Refugees from Central Europe' by Irene Eber. De Gruyter, 2012. |

|

Bank of China 5 Yuan, 1918. Shanghai branch.

A lithographed forgery with signatures of the 1923-28 period of issue. The poor condition of this note shows that this fake circulated well and may never have been detected - though it shows more clearly as fake than the 1918 Tientsin example above. |

Bank of Communications 5 Yuan of 1914, Shanghai branch.

A lithographed forgery with a curious mistake: the signatures show the forgery to have been produced in the 1930s but the serial number prefix would not appear on these issues of this period. All red 10 Yuan issues put into circulation from the mid 1920s onwards had the 'S' letter prefix. Only the very earliest issues had other prefixes. |

|

Bank of China 5 Yuan of 1926

A lithographed forgery possibly by the same forgers as the other Bank of China examples. The note seems to have circulated well (and carries a few red merchants chops) before being discovered, stamped with the large purple cancellation seals and withdrawn. The signature of Fen Gengguang (left sign.) dates the note to 1926, as he briefly served as acting governor during that year. |

The Central Bank of China 20 cents of c.1927

Another lithographed counterfeit - fairly clumsy and especially revealing with the off-coloured yellow underprint of the front, and the crude appearance of the pagoda vignette. |

|

The Central Bank of China 1 Yuan of 1936

This was a form of safe conduct pass which bore the standard face of the note. The reverse however was altered to incorporate messages promising safe passage for the bearer into the territory held by the Nanking (Japanese puppet) government. At least one other version is known with a varying text. |

The Farmers Bank of China 10 Cents of 1937

A product of the Japanese puppet government of China at occupied Nanking (Nanjing). This note appears as the third known in a series of Japanese propaganda 'parody' issues. This note bares the correct face though the format of the serial number is wrong - the reason being that it was intended to match that of the reverse. The reverse is yet another scaled down version of that used on the original parody note of the Central Bank of China 1 yuan of 1936, and even retains the signatures of the Central Bank of China officials. |

Above: Central Reserve Bank of China (Japanese puppet bank) 5000 Yuan of 1945. The upper left (front only) note is genuine, the lower left (front only) is a fake identified by the bank or other authority with cancellation overprints in Chinese. The low quality of the genuine notes must have made forgeries harder to spot and the only obvious differences are the slightly clumsier portrait and the thinner block letters. Above right is another forgery of this note, possibly by the same counterfeiter. Unlike the other example, this note has cancellation overprints in Chinese and English and has further been punch cancelled.

Old Forged overprints and other altered genuine notes

|

Bank of China 100 Yuan of 1940.

The early issue of this note which carries the serial numbers on both sides. This type is found both with and without a black overprinted 'Chungking' in Chinese and English (engraved in the later issues). Chungking was the wartime capital of China: banknotes were stamped with the placename in an attempt to prevent their circulation outside of Nationalist controlled territories, and to curb the circulation of money from outside the region which may have been sourced from the Japanese occupiers. This scheme seems to have been abandoned long before the end of the war. This particular example however has no English name printed on the back, and two very smudged Chinese place-names on the front. A likely explanation is that someone arrived in the vicinity of Chungking with one or more of these unstamped versions and attempted to add the overprint so the note would be accepted. |

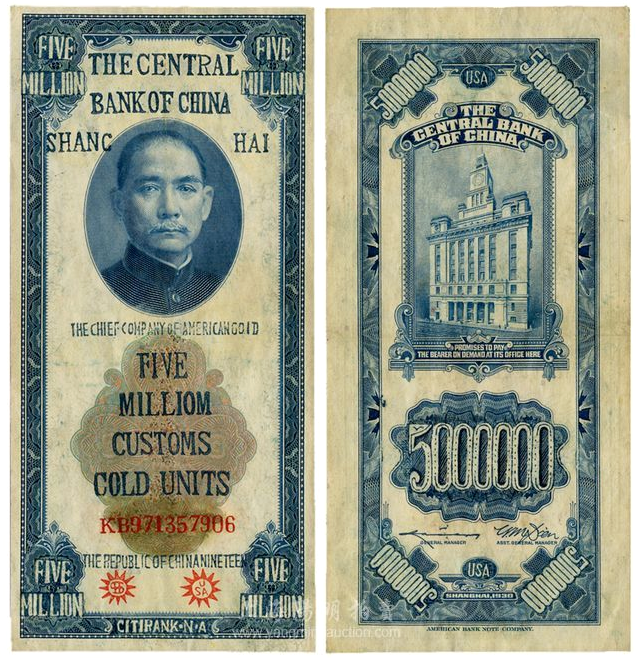

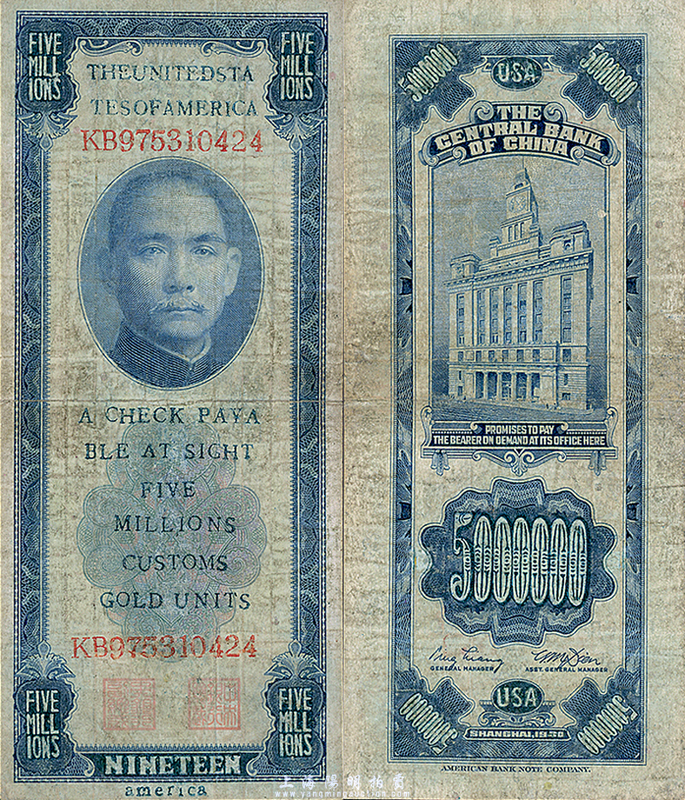

The Central Bank of China 500 CGU of 1930.

This genuine note has been crudely and extensively altered to create a '5 million customs gold units' note, removing all of the Chinese text and adding such as references to 'Citi Bank'. Most likely created in the weeks leading up to the 1948 currency reforms in which the CGU was scrapped having, like the Yuan, succumbed to severe inflation. There are some appalling spelling mistakes - a very odd item. |

|

Bank of China 1 Dollar of 1917.

A one dollar altered to create a 10 dollar note, which works more successfully on the front, than the back. The characters and numerals have been inked or painted on to paper, cut out and then glued on. A rare note, altered or not. |

The Central Bank of China 500 CGU of 1930.

Another 500 CGU note altered to 5 million CGU; this one is a somewhat more successful attempt than the previous 500 CGU - it clearly circulated well and is a less crude effort than the above example though still with serious flaws such as the words split over two lines. An interesting relic of the hyper-inflation of the end years of the Nationalist regime. |

Hong Kong

|

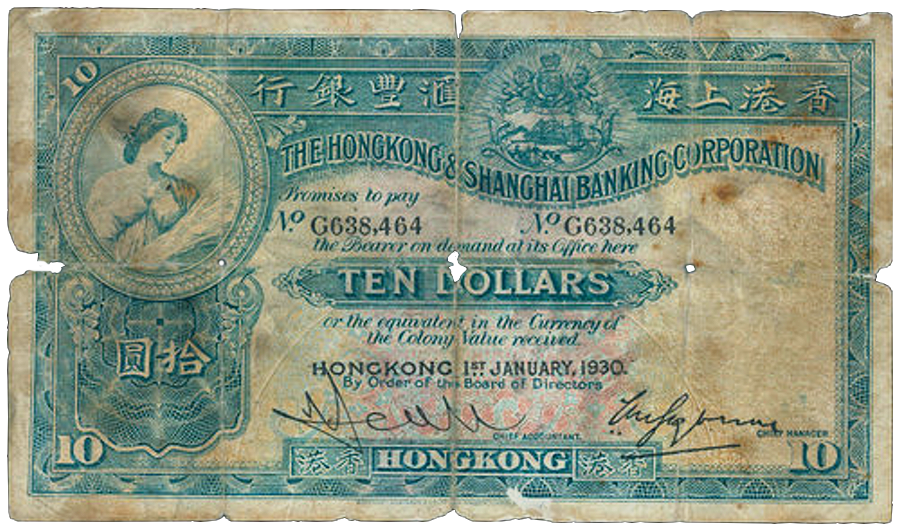

Two counterfeits of $10 of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC).

Right: the more convincing forgery of a 1930 issue; extremely well circulated and clearly never detected. Below: a fairly good quality but clearly lithographed forgery of a 1923 issue. Even more heavily circulated and again unmarked as a detected counterfeit. It's likely that many users of this note were aware of it's status - too late - but kept passing it along as $10 would have been too much for most to lose at the time. |

Miscellaneous Asian forgeries

|

Laos (Banque Nationale Du Laos) 5 Kip of 1957

The Communists (Pathet Lao) engaged in an unusual counterfeiting operation, targeting the 1957 issues of the Security Banknote Company. Their status as forgeries is unusual as they were intended to circulate properly as currency. Many of these notes are still in existence and few it would seem realise their significance, assuming perhaps that they were simply a later re-issue. The main difference between these and the genuine notes, is the lack of the planchettes (coloured security dots). These forgeries are thought to have been printed in either Bulgaria or the former Czechoslovakia - though there is a suggestion that these were produced in China. It seems that during at least two periods these notes were placed into circulation for actual use as currency during 1958 and later in the early 1970s. The following information is provided on the Modern Forces site: "Until very recently, all that was known about these forgeries was that during the war in Laos the Communist forces forged the 1, 5, 10 and 50 kip banknotes of the Kingdom of Laos Banque Nationale du Laos notes of 1957. The forgeries were first said to be printed in Bulgaria and meant to weaken the |

National Government (Note: the forgeries are described as emanating from Czechoslovakia in Area Handbook for Laos, DA PAM 550-58 1972).

The forgeries were good enough to fool the common Lao peasant, but there were some major errors in the printing. For instance, the most noticeable is that the paper of the original banknotes has small colored security dots that are missing in the forgeries. These communist-produced “Vientiane kip” notes were first used to help finance the formation of a short-lived coalition government headed by Prince Souvanna Phouma. In the early 1970s, the replicas were used by the Lao People’s Revolutionary party (whose military arm was the Pathet Lao) as military occupation currency in areas under their control.

A Chinese reference book entitled Contemporary China’s Banknote Printing and Minting for Foreign Countries, China Financial Clearing House, 2000, was found by a specialist in Lao currencies in 2007. The book mentions that the Chinese prepared banknotes for Cuba, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Mongolia. It also states that the Pathet Lao banknotes were printed in the Shanghai banknote printing facility in April 1968, and the banknotes were legal tender in their “liberated” areas. Apparently, there was a secret agreement between the Royal and Pathet Lao governments for each to circulate their own banknotes with the same basic design. The Royal Lao government had their banknotes printed in the United States and the Pathet Lao had theirs printed in China. (note: there may be some confusion here with the various series printed by the Chinese at Shanghai, such as the SCWPM Laos P19A 1 Kip, etc).

In 1970, a former CIA agent stated that his forces captured a cave complex holding the Pathet Lao supply of banknotes. It was a very large number of banknotes and all were flown back to Vientiane. At first, the captured banknotes were going to be overstamped with a propaganda message and dropped over Pathet Lao “liberated” areas, but there were far too many banknotes and too few personnel to do the job. It was then decided to just drop them over the “liberated” areas and ruin the economy with a large amount of currency chasing few goods and services.

This operation led to spurious report of the United States forging Laotian currency. Rumors of a CIA-sponsored forgery project have circulated since the early 1970s. Christopher Robbins, in Air America, Putnam & Sons, 1979, page 132, writes:

Another top secret Agency project involved dropping millions of dollars in forged Pathet Lao currency in an attempt to wreck the economy by flooding it with paper money. Pilots on routine night drops would be asked to return over Communist lines drop several packages. It turned out the packages were full of counterfeit money.

Air American pilot William Wofford said:

We must have dropped two hundred pounds weight of money, hundreds of millions of kip. They were just in paper bags and had these devices the kicker pulled which ignited a small charge and blew the bag apart. The money was packed loosely, and when the bag blew the money would scatter and drift all over the area. I’m sure a few people ate well the next day. When we got back to Vientiane, we had to spend two hours cleaning the airplane because some of the bags burst before we could get them out and we had counterfeit money from one end of the airplane to the other.

A pilot told me:

The C-130A's at Naha, Okinawa, had several different missions dropping PSYOP leaflets in Vietnam, North Vietnam and Laos; and counterfeit currency in North Vietnam. All of the leaflets were printed in Okinawa.

The United States produced a great number of general nation-building leaflets in support of the Royal Laotian government in their fight against the Communist Pathet Lao. The same American PSYOP specialists who were printing leaflets for Vietnam printed many of the Laos leaflets."

Source: Modernforces.com psyops article

A Chinese reference book entitled Contemporary China’s Banknote Printing and Minting for Foreign Countries, China Financial Clearing House, 2000, was found by a specialist in Lao currencies in 2007. The book mentions that the Chinese prepared banknotes for Cuba, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Mongolia. It also states that the Pathet Lao banknotes were printed in the Shanghai banknote printing facility in April 1968, and the banknotes were legal tender in their “liberated” areas. Apparently, there was a secret agreement between the Royal and Pathet Lao governments for each to circulate their own banknotes with the same basic design. The Royal Lao government had their banknotes printed in the United States and the Pathet Lao had theirs printed in China. (note: there may be some confusion here with the various series printed by the Chinese at Shanghai, such as the SCWPM Laos P19A 1 Kip, etc).

In 1970, a former CIA agent stated that his forces captured a cave complex holding the Pathet Lao supply of banknotes. It was a very large number of banknotes and all were flown back to Vientiane. At first, the captured banknotes were going to be overstamped with a propaganda message and dropped over Pathet Lao “liberated” areas, but there were far too many banknotes and too few personnel to do the job. It was then decided to just drop them over the “liberated” areas and ruin the economy with a large amount of currency chasing few goods and services.

This operation led to spurious report of the United States forging Laotian currency. Rumors of a CIA-sponsored forgery project have circulated since the early 1970s. Christopher Robbins, in Air America, Putnam & Sons, 1979, page 132, writes:

Another top secret Agency project involved dropping millions of dollars in forged Pathet Lao currency in an attempt to wreck the economy by flooding it with paper money. Pilots on routine night drops would be asked to return over Communist lines drop several packages. It turned out the packages were full of counterfeit money.

Air American pilot William Wofford said:

We must have dropped two hundred pounds weight of money, hundreds of millions of kip. They were just in paper bags and had these devices the kicker pulled which ignited a small charge and blew the bag apart. The money was packed loosely, and when the bag blew the money would scatter and drift all over the area. I’m sure a few people ate well the next day. When we got back to Vientiane, we had to spend two hours cleaning the airplane because some of the bags burst before we could get them out and we had counterfeit money from one end of the airplane to the other.

A pilot told me:

The C-130A's at Naha, Okinawa, had several different missions dropping PSYOP leaflets in Vietnam, North Vietnam and Laos; and counterfeit currency in North Vietnam. All of the leaflets were printed in Okinawa.

The United States produced a great number of general nation-building leaflets in support of the Royal Laotian government in their fight against the Communist Pathet Lao. The same American PSYOP specialists who were printing leaflets for Vietnam printed many of the Laos leaflets."

Source: Modernforces.com psyops article

|

South Vietnam 500 Dong of 1966 This forgery example is stamped 'BAC GIA' (which is the name of a town in South Vietnam?) presumably to designate it as a forgery. The holes are due to this being one of a group of forged notes strung together for storage. There are at least two versions of this forgery - possibly a product of the Viet Cong? Apparent widespread forgery of this note may be the reason behind it's early withdrawal, in 1970. This example does have a crude watermark. |