Shanghai - 上海

|

Updated December 20 2020 |

Section 2: The Currency

A diverse array of paper money was issued out of Shanghai - and as the financial centre, something of everything and anything of China's vast variety of currency probably passed through it's businesses, banks and money exchange shops at some point. Numerous Chinese government, commercial and foreign banks had headquarters and major branch offices in Shanghai. Various forms of emergency money were also issued during frequent periods of crisis when coinage in particular was in short supply.

This page will be periodically expanded.

This page will be periodically expanded.

The Money

The Bank of China 中國銀行

|

The Bank of China was founded at Shanghai in 1912, out of the re-organised Ta-Ching Government Bank. It was headquartered in Peking until 1927 when the head office was relocated to the former German Concordia Club building on the Bund at Shanghai (below). This was subsequently rebuilt and replaced with the art deco skyscraper which remains, though no longer used as the banks head office (right). |

On March 21 1941, 'puppet' police from the Japanese occupied sections of the city in which the Bank of China's residential compound was situated (outside of the International Settlement), stormed the property and dragged bank staff from their beds. 128 of the staff were abducted and confined at the dreaded headquarters of the secret police security service at 76 Jessfield Road in Shanghai. These people were retained as hostages with the intention of halting further attacks on puppet banking facilities by the Chungking government. However the Nanking government itself launched more of it's own terror attacks on pro Chungking establishments the following day. Chungking agents eventually attacked and killed a senior officer of the puppet Central Reserve Bank. Nanking agents retaliated by murdering the chief cashier of the Bank of China's main Shanghai branch. Later the same day, a further three employees of the Bank (of those held at Jessfield Road) were executed. The remaining Bank of China staff and their families vacated the residential compound and it was taken over by the puppet Central Reserve Bank of China - which was probably the real motivation for the hostages and executions.

Source: The Danwei: Changing Chinese Workplace in Historical and Comparative Perspective by Xiaobo Lu. Routledge, 24 Feb 2015, pages 74-76.

|

Right: Bank of China 1912 provisional issue $10 on notes created for it's predecessor; the Ta Ching Government Bank $10 of 1909. The portrait is of the important Qing politician, general and diplomat Li Hong Zhang (1823-1901). From later in 1912, redesigned versions of this series would be issued with the new Bank of China titles, and the portrait replaced with that of the deified mythical ancient emperor Huang-Di (The Yellow Emperor). All were printed by the American Banknote Company, though the overprints were presumably applied in China. The back vignette depicts the city walls and gates of Peking (Beijing), with a canal in the foreground. |

|

Right: the short lived 1935 (1936) Shanghai branch 5 yuan. This, the first version of this note was only issued for around 6 months before being replaced with the somewhat more common type without a branch name. This was the last Bank of China note to be issued with the Shanghai (or any) branch name, except that of Chungking.

Dr Sun Yatsen and the Beihai Park White Dagoba in Peking (Beijing) are depicted on the front. The reverse shows the new Bank of China headquarters on the Bund. This however was not yet complete at the time of issue. |

The Central Bank of China (1928) 中央銀行

|

A national bank officially established by the Kuomintang at Nanking on the 5th October 1928 as a state institution, a 'central bank,' and inaugurated at Shanghai in November 1928. This succeeded the Central Bank of China known for issuing the '1923' series. This first entity was actually the Kwangtung Provincial Bank temporarily reformed to function as a quasi-national bank in 1924. It's purpose was to serve the needs of the military government established in 1917 by Sun Yatsen at Canton, as it embarked upon campaigns to defeat the northern, warlord dominated Beiyang Government at Peking (Beijing), and to stabilise the monetary situation in Kwangtung (Guangdong). The bank returned to this role from 1928. According to Linsun Cheng in "Banking in Modern China" (2003, p129) the Central Bank of China did not actually function as a true central bank until 1935 (the year of major government banking and currency reforms), due to "it's relatively small capital and weak credit". The bank was designated as the sole (officially) issuer of currency after 1942, until 1949. This restriction had no effect on areas outside of Kuomintang control, and even within; the Farmers Bank of China issued what was currency in all but name during 1943-44. |

Above: The Shanghai Bund headquarters of the Central Bank of China from November 1st 1928. This building was originally constructed as the Shanghai office of the Russo-Chinese (later Russo-Asiatic) Bank. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (WWII), it was held by the 'puppet' Central Reserve Bank of China.

|

The bank was headquartered at Shanghai, however in 1937 the headquarters was relocated to Hangchow (Hangzhou) due to bomb damage sustained during the Japanese attack and occupation of most of the city. It was later moved again, to Chungking, not returning to Shanghai until after the 1945 defeat of the Japanese.

During the Sino-Japanese War, in the months before Japan took full control of all of Shanghai, there was an ongoing campaign of violence and terrorism conducted between the agents of the Nanking puppet regime of Wang Jingwei, and that of the Chungking government. Part of the violence was targeted at the financial institutions of both regimes. In March 1941, two bombs were successfully detonated by pro Japanese agents at branches of the Central Bank of China. The first destroyed most of the second storey of the Burkhill Road branch, killing one person and injuring 38 others. In the French Concession meanwhile, a bomb blew apart the Canidrome branch, killing seven and wounding 21.

|

Right: Central Bank of China 1 Dollar (National Currency) of 1928, issued c1930. (SCWPM 195b). Printed by the American Banknote Company. This well known series is unusual for having the portrait - of Dr Sun Yatsen (Sun Zhongshan) on the reverse - a characteristic shared with some of the issues of the Canton Municipal Bank. This particular example, as with many of the period, is overprinted by the bank with a set of marks (which can be various combinations of letters, numbers, characters or symbols) indicating that the note was issued by a bank or business other than the Central Bank itself. |

|

Right: Central Bank of China 5 Dollars (National Currency) of 1930, issued c1932. (SCWPM 200a). Printed by the American Banknote Company. A well known issue commemorating Sun Yat-sen that was clearly based on the US Lincoln $5. This particular example shows it's circulation well; with numerous commercial chop marks. The note again carries overprints indicating that it was placed into circulation by a bank or business other than the Central Bank. |

|

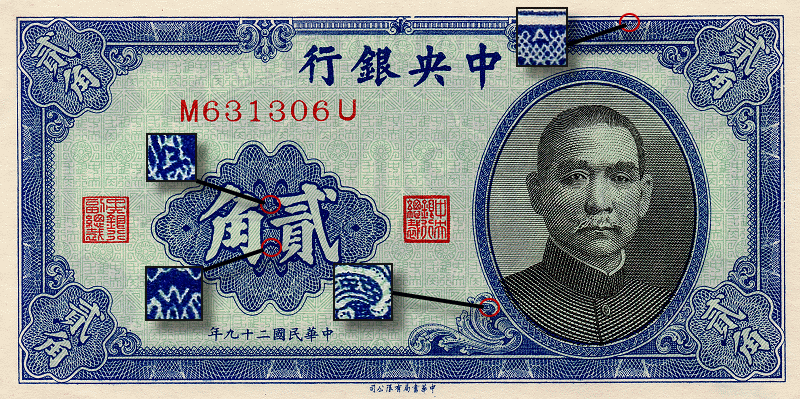

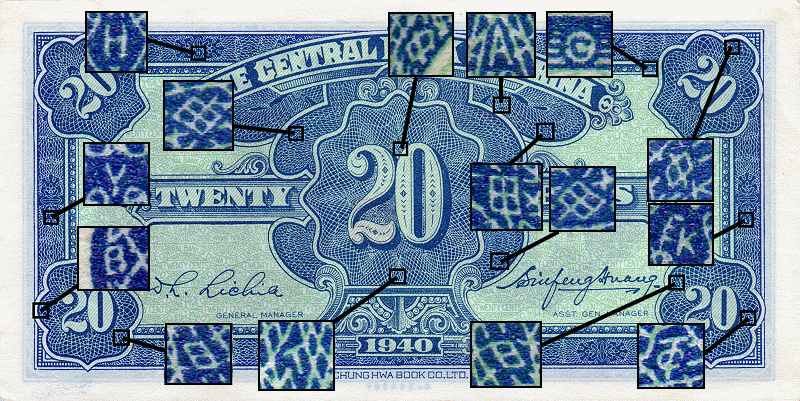

Left: Central Bank of China 20 Cents of 1940. (SCWPM 227a). Printed by the Chung Hwa Book Company at their Hong Kong site.

These were produced mainly for Shanghai, due to a severe shortage of small change. Hidden lettering in Chinese and English on both sides of this note, plus other design 'quirks' - possibly a security feature due to realistic concerns of Japanese forgery, or even meant as a coded message for recipients within the International Settlement of Shanghai which remained under nominal Nationalist control at the time of issue. Though tiny hidden characters, letters and other features are often found on notes, the 10 and 20 cent notes of this series carry them to an unusually excessive degree. For details; see the images below. An incomplete partial sheet of these notes was recently found that had been re-used for a test printing of puppet Japanese Central reserve bank notes. |

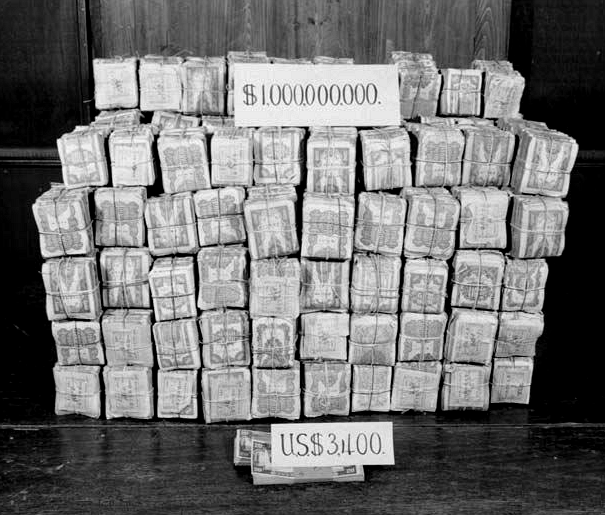

Left: 'Payday', Shanghai, 1947 (LIFE Magazine). This cheery group are holding tightly packed bundles of Central Bank of China notes. Right: 1947, A Billion Yuan stack of these bundles - equivalent to $3400 US. These particular bundles are a mix of standard 1947 Central Bank issues and Customs Gold Unit issues.

The Bank of Communications 交通銀行

|

This government/commercial bank was established at Peking (Beijing) on March 4th 1908. The Shanghai branch was set up in May 1908. It was chartered as "the Bank for developing the nations industries", and took charge of the funds related to shipping, rail, telegraph and postal services. The headquarters was moved from Peking to Shanghai in 1928. The bank was reorganised in 1933, leading to a new General Manager (and Shanghai branch Manager), and from 1935 the government had majority control. The bank within Japanese controlled areas was re-organised and cut off from nationalist control in 1942. The 1914 series: the best known BofComm series, which was issued until the late 1930s. The $10 is found in a variety of colours (including a mysterious monochromatic issue) and depicts the neo-gothic Old Customs House on the Shanghai Bund, later replaced by the building which still stands today and is depicted on all Customs Gold Unit issues of the Central Bank of China. Upper-Right: a heavily used but somewhat spectacular example of the series of 1914 10 Yuan of the Shanghai branch, SCWPM 118o, issued c1925-27. This fascinating note has over 36 chops marks and annotations across both sides and seems to have been cancelled with burnt holes through the signatures. Right: A rare early issue of the 1914 series for the Shanghai branch, in green. Most likely issued 1915-23. Few of these survive due to the political and financial termoil of the period. |

Commercial Banks

A small selection from the many note issuing commercial banks of pre-war Shanghai, from the major to the minor.

The Agricultural and Industrial Bank of China 中國農工銀行

|

Little information is readily available for this once major commercial bank. It is known that T.L Soong (brother of T.V Soong and Mei-ling Soong - Madam Chiang Kai-shek) once held a directorship. In 1944, the bank part funded a Sino-International economic research centre based in New York. Right: a 1 Yuan of 1932 issued from the Shanghai branch, printed by the American Banknote Company. The vignettes are similar to those used on the later issues of the (Government) Farmers Bank of China. They most likely derive from the same source, the ‘classical’ agricultural scenes from the Southern Song Dynasty book; 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' (Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture) |

The China & South Sea Bank Limited 中南银行

|

The China and South Sea Bank was founded in Shanghai, July 15th 1921, by Huang Yizhu and Xu Jingren - overseas Chinese from Indonesia. One of the few Chinese owned banks to gain real public confidence; it’s notes circulated widely in Shanghai and Hong Kong. It had many branches: Beijing, Tianjin, Hankou, Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Xiamen, Guangzhou and Hong Kong. It’s mainland operations were nationalised by the People’s Republic of China in 1951. The Hong Kong branch continued until absorption by the Bank of China (Hong Kong) in 2001. Right: a 1 Yuan (National Currency) of 1921, printed by the American Banknote Company. The front depicts a sundial at centre; located at the Guozijian or Imperial College (attached to the Temple of Confucius) at Beijing. This was the highest institution of learning in China's Imperial educational system. |

The Commercial Bank of China 中国通商银行

|

China's first modern private bank, founded at Shanghai as the Imperial Bank of China in 1897 by Sheng Xaunghi. Sheng hired a former employee of the HSBC, A.M. Maitland (an Englishman) to manage the foreign staff and a well connected Chinese banker, Chen Shengjiao, to manage the Chinese staff. The English name changed to the Commercial Bank after the 1911 Revolution; however the Chinese name did not alter. Due to the growing financial crisis which peaked in June 1935, the Commercial Bank of China was one of three important commercial banks which found themselves unable to redeem their currency and were forced into reorganisation. The management were compelled to resign and were replaced by government officials and government money was invested into the banks bringing them firmly under state control. It is believed that this crisis was mainly staged by government which had retained vast quantities of the currency of these banks within it's own institutions, and then redeemed them 'on-mass' to force the crisis. Source: (The Shanghai capitalists and the Nationalist government, 1927-1937 By Parks M. Coble (p188-89) Upper right: the Neo-Gothic headquarters of the bank, located on the Bund. Right: $5 of 1926 printed by Waterlow & Sons Ltd, London. The Shanghai Bund is depicted on the left and, Lu Xing - a Daoist God of Wealth & Status, at right. The note carries overprints indicating that it was issued by another bank or business, as well as a variety of merchants chop marks and annotations. |

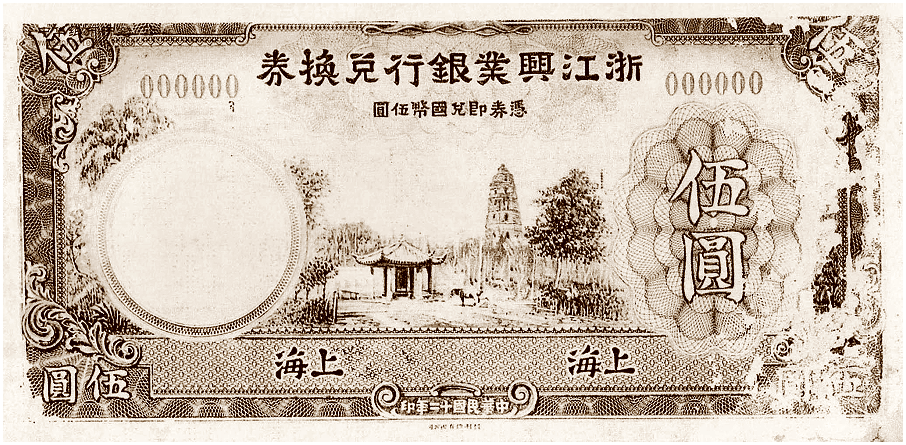

The National Commercial Bank 浙江興業銀行

|

Founded in 1907 by the Zhejiang Provincial Railway Company in Hangchow (Hangzhou), with the aim of supporting industrial development. The bank made numerous low interest loans to Chinese businesses. The bank also dealt in real estate. The Shanghai branch opened in August 1908 and began issuing notes shortly after. It had an unusual policy of maintaining a 100% cash reserve against it's issued notes, which would prove to save the bank from several financial crises. The headquarters of the bank was moved to Shanghai in 1915, and during this period the bank was re-organised. The end result saw it develop in to one of the most successful of the Chinese private banks. However, decline set in after 1928, partly due to a poor relationship with the Nationalist Government. The bank's president Ye Kuichu (chairman 1915-1950) distrusted Chiang Kai-shek and was reluctant to loan money to support the Northern Expeditionary armies. Currency issued ceased in 1935 in line with the governments monetary reforms. Upper right: the stunning Shanghai branch 1 Dollar of '1907', depicting a rooster and a bearded gentleman: mostly likely a Taoist wealth deity. The note was however issued sometime after 1915. Right: a damaged photo of one of a series of designs by the London printer De La Rue for a 1923 issue by the bank. Sadly these were not adopted. |

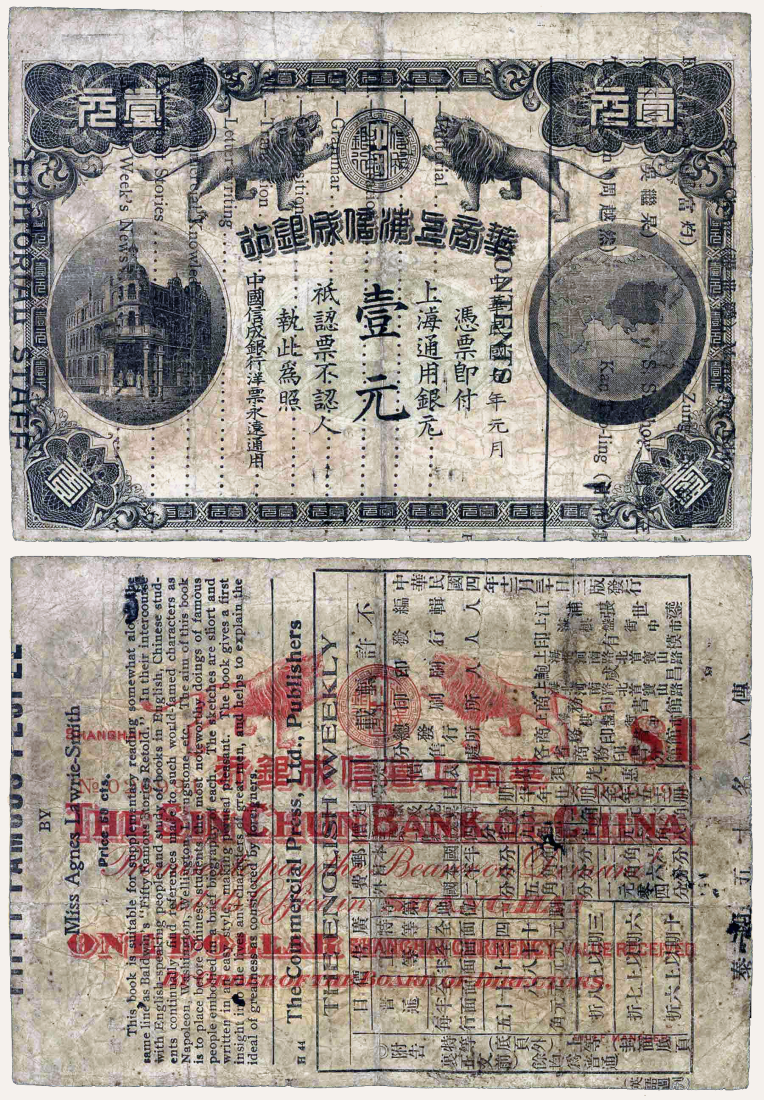

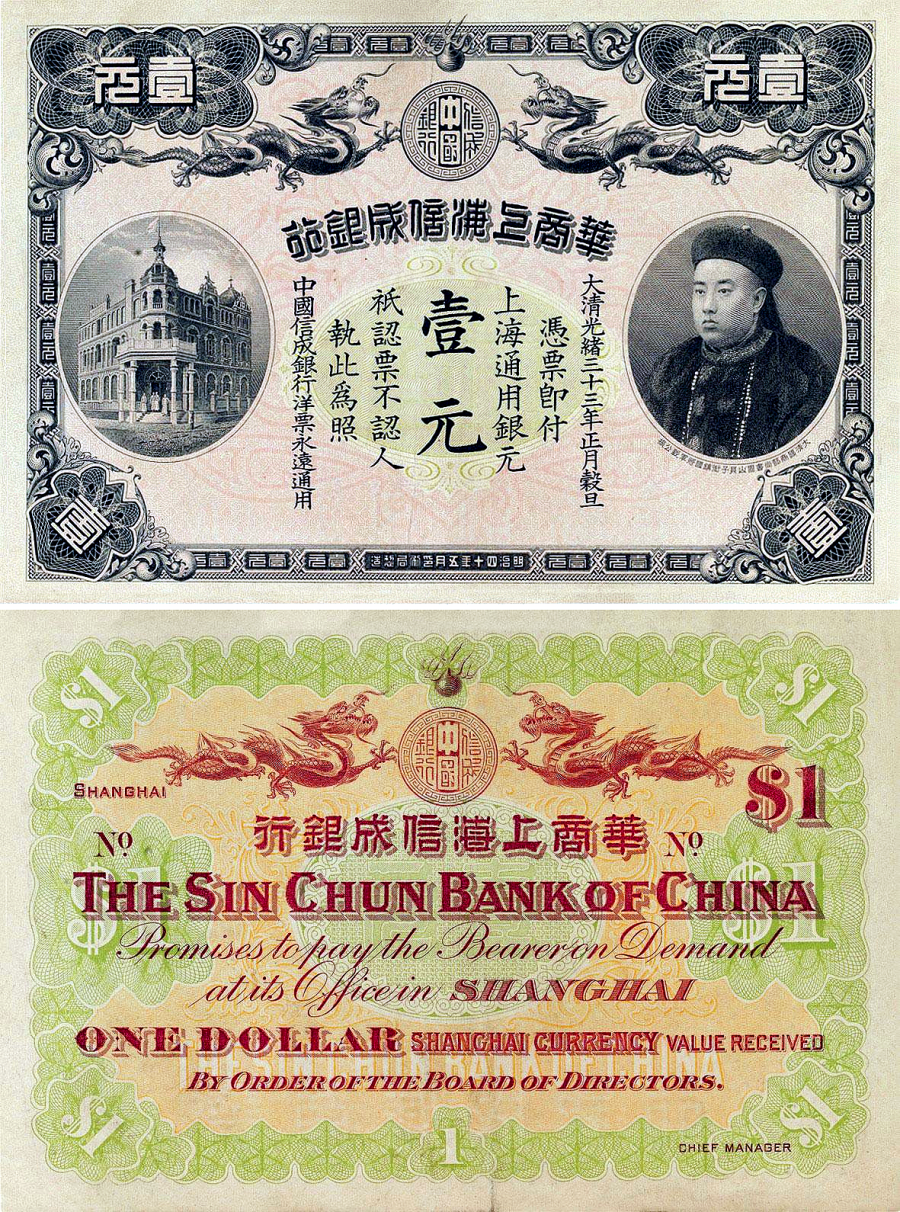

The Sin Chun Bank of China 華商上海信成銀行

|

Right: Currency of the Sin Chun Bank is found in 1, 5 and 10 Dollar denominations, dated 1907, for branches in Shanghai and Tientsin. The front depicts the headquarters (in Shanghai?) and a portrait of Jui Gung Jan (Qing Minister of Commerce). All known examples are remainders, lacking serial numbers and signatures; it is unclear whether these notes were ever issued. The fate of the bank is also unknown. However, see below and right. |

Left: A trial printing for a Sin Chun Bank of China 1912 Shanghai $1, with serial numbers on the reverse. This was tested on old newspaper. This would seem to indicate that the bank was in operation for some years and must have issued and circulated some paper currency, even if no such examples appear to have survived. |

Yah Kong Native Bank - 协康钱庄 (?)

International/Foreign Banks

The Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) 香港上海匯豐銀行

|

The HSBC was the largest and most important of the foreign banks in China, established in Hong Kong in 1865 to finance trade between China and Europe, issuing currency within the treaty ports, most significantly Shanghai. It was, and remains the principal bank and note issuer in Hong Kong.

The founder, a Scotsman named Thomas Sutherland, wanted a bank operating on "sound Scottish banking principles." The original location of the bank was considered crucial and the founders chose Wardley House in Hong Kong since the construction was based on some of the best feng shui in Colonial Hong Kong! After raising a capital stock of HK$5 million, the "Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Company Limited" opened its doors on 3 March 1865. It opened a branch in Shanghai during April of that year, and started issuing locally-denominated banknotes in both the Crown Colony and Shanghai soon afterwards. The bank was incorporated in Hong Kong by special dispensation from the British Treasury in 1866, and under the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Ordinance 1866, a new branch in Japan was also established. The bank was closely tied to the Imperial Maritime Customs, which used the banks services. The bank dealt extensively in loans to the Chinese government, for diverse purposes including railway construction and the military. During the Asia-Pacific War, the HSBC in Shanghai along with nearly all other foreign banks, was siezed and liquidated by the Japanese banks. The Yokohama Specie Bank took on some of the HSBC's key roles, including the handling of customs and salt administrations. Upper right: The famous headquarters building of the HSBC, located on the Shanghai Bund. This 1930s photo's shows the Union Jack flags, emphasising the British origin and ownership of this bank. After the 1949 revolution, the bank was used as the regional headquarters of the Communist Party. Right: HSBC Shanghai branch issue $10, 24th July 1920. Printed by Bradbury & Wilkinson. SCWPM S357A. |

The American Oriental Banking Corporation 上海美豐銀行

|

Incorporated in Connecticut and established at Shanghai in 1917. The majority shareholder was the American Raven Trust Co., the remainder was held by Chinese investors. An attempt to expand the bank in the mid 1920s was abandoned due to the civil war. The bank closed in 1935 due to the failure of it's foreign exchange business and the financial misdemeanors of it's founder Frank Raven, who was prosecuted in China and in prison (briefly, and in the USA) by 1936. Most American customers had lost everything; many Chinese customers however did not trust bank accounts - and were proven right - they had only used the banks safety deposit facilities. Right: A Shanghai branch issue 5 Dollars (Local Currency) of 1919, printed by the American Banknote Company. SCWPM S97. Frank Raven's signature as president appears on the back, at left. |

Japanese Occupation (Puppet) Banks

The Hua Hsing Commercial Bank 華興商業銀行

|

The Hua Hsing Bank was established in Shanghai in 1938 by the Japanese, in support of their newly created puppet state 'The Reformed Government of the Republic of China' founded at Nanking (Nanjing). This was later merged into Wang Jingwei's Nanking Nationalist Government in 1940. At it's creation, The Chinese government at Chungking contacted foreign governments inlcuding the the UK and USA advising them not to deal with this new bank which threatened shared financial interests. The US government advised American banks in Shanghai to resist in any way from assisting this new bank and the circulation of it's currency. The Chinese government itself forbade all Chinese banks, firms and retail establishments to accept or circulate these new notes. Their value diminished, however they continued in circulation until they were withdrawn in 1940 in favour of the currency of the then newly created puppet Central Reserve Bank of China. The Hua Hsing Bank was abolished following the 1945 defeat of Japan. Right: the scarce 1 Yuan note of 1938. Printed by the Letterpress Co. in Tokyo. All issues by this bank are scarce to rare. |

The Central Reserve Bank of China 中央儲備銀行

|

The first series of notes, assigned to or dated 1940 were probably not issued or even printed, until the following year. These CRB notes became virtually the only currency allowed to circulate in Shanghai and the rest of occupied Southern China. The Japanese set up the Central Bank of China (CRB) in Nanking after they invaded southern China. This puppet bank was created in 1940-41 to serve the needs of the Japanese controlled Nanking regime of Wang Jingwei, self styled as the Republic of China. It is probably not coincidental that the name of the bank - The Central Reserve Bank of China - was that originally intended for the re-organised Central Bank of China following the Kuomintang Governments currency reforms of 1935. That scheme never transpired. The abandoned Central Bank of China building on the Bund at Shanghai which the Japanese had taken control of in November 1940, now became the Shanghai branch of the new Central Reserve bank, opened on January 20th 1941. After the Pacific War erupted in December 1941, the CRB engaged in the process of dissolving and reorganising Nationalist government banks in Shanghai, cutting them off from Chungking. Currency issue began quickly, however the bank encountered difficulties in circulating the money among the Chinese who rightly viewed it as illegitimate. On May 16 1941, the Wang Jingwei government issued a decree making it a prosecutable offense to refuse to accept the CRB notes. Further, from June 25 1942, the fabi (Nationalist currency) was no longer legal tender in Shanghai, Nanking and other major regions of Japanese control. Initially stable, the notes however collapsed in value from late 1944 due to excessive issue. Due to rising inflation higher and higher denominations were needed, leading to issues of 1,000, 5,000 and 10,000 yuan notes. A 100,000 Yuan was produced but never circulated. The 10,000 Yuan example (right) despite a date of '1944' was actually printed and issued in 1945 and was among the very last issued. In addition to the high denomination, the note has been reduced in size and the serial numbers abandoned for block numbers. The notes became obsolete following the defeat of Japan and an exchange rate to fabi was set at 200 to 1. The 10,000 would have been exchanged for a mere 500 yuan. |

Above: the 100 Yuan of 1944 (1945), SCWPM J29.

All Central Reserve Bank notes depict the Sun Yatsen Mausoleum at Nanking (Nanjing) and most carry Sun's portrait. The intention of course was to convery legitimacy to the currency by using such nationalistic imagery. This didn't work, and acceptance had to be forced. Above: the 10,000 Yuan of '1944' (1945), SCWPM J39.

|

Miscellaneous Commercial Scrip Money

|

Clube Lusitano

Founded in 1910, the Clube Lusitano was a Portuguese members club in Shanghai, located on the top floor of the Pearce Apartments building (1933-41). The address (until 1933) given in the 1925 Comacrib Directory of China; N.789-32N Szechuen Road. (Chairman: J.A dos Remedios). It was to move twice more, in 1941 and 1948. A centre for the Portuguese community in Shanghai, the club held regular dances and engaged in sporting contests with members of other Shanghai clubs, such a football match held at the Bubbling Well Road racecourse in 1941 with members of the Jewish Recreation Club. The club closed in 1950 with the government banning of western style dancing. Right: At some point in the early 1940s, the club issued a scrip note for 10 Cents "CRB" (the Japanese puppet Central Reserve Bank of China) utilising now obsolete small red 1 cent notes of the Central Bank of China. Overprinted in black "Clube Lusitano Ten Cents C.R.B. (For use of members only), the front has a Portuguese cross in the middle. |

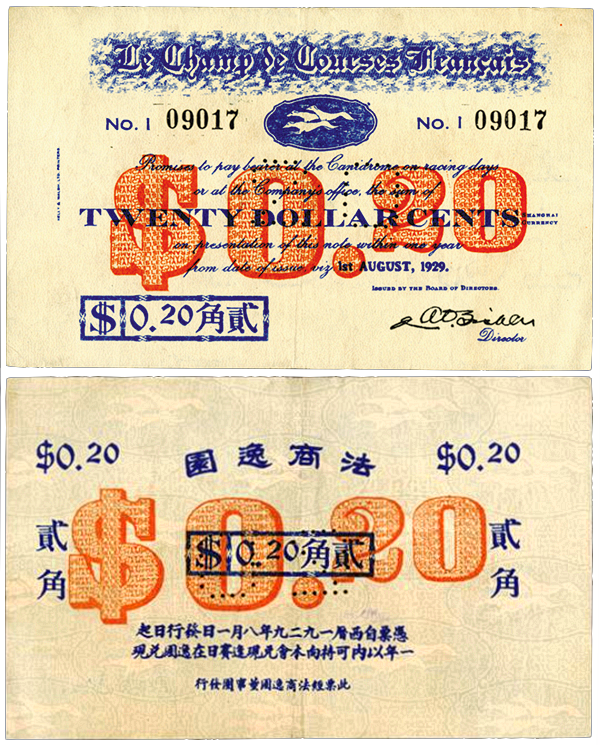

Le Champ de Courses Francais

|

The Champ de Courses Canidrome was a greyhound racing track in the French Concession at Shanghai, opened November 18 1928. A Chinese government crackdown on gambling led to the closure of the Canidrome's main rivals in around 1930, but the track itself seems to have held out, boosted by the demise of it's competition. It is listed in a guidebook of 1938 and referred to as the 'Rendezvous of Shanghai's Elite'. Right: a 20 cents scrip note issued in August 1929 and valid for one year. |

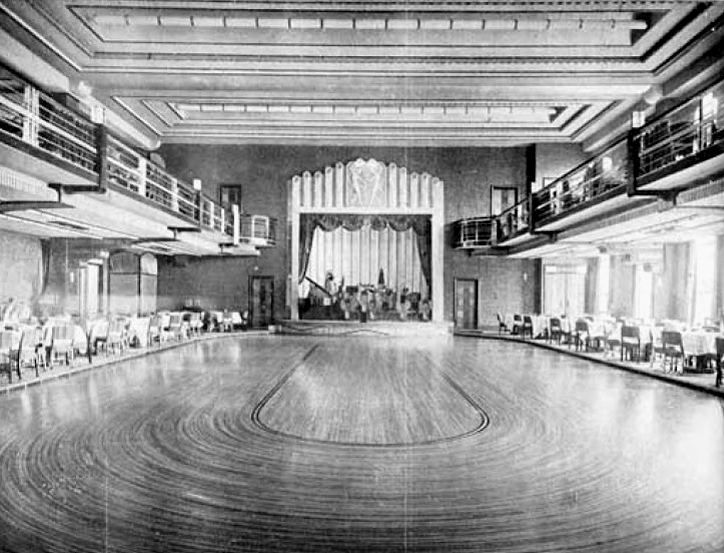

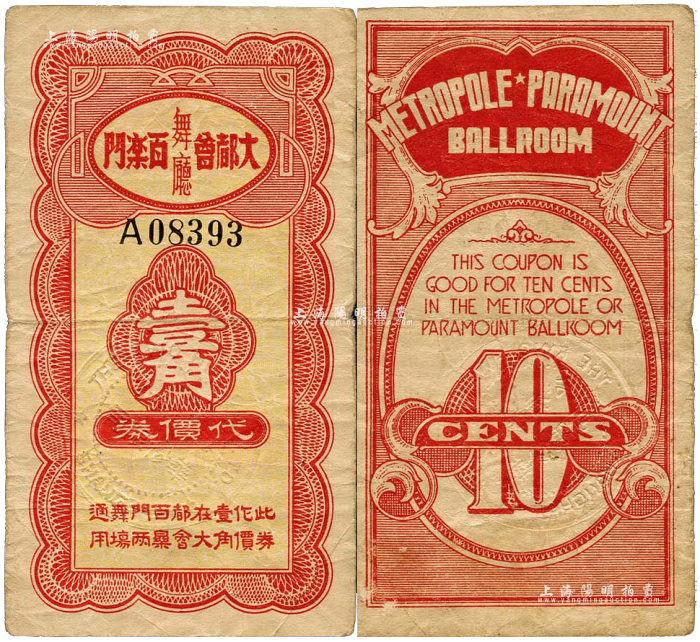

Metropole / Paramount Ballroom(s)

|

Built in 1935 and designed by architect Yang Xiliu (who was also responsible for the Paramount) Metropole Gardens Ballroom (right), was modeled on an ancient Chinese palace. It was located on the then Gordon Road. Low running costs enabled low prices to be passed on to customers, attracting a far wider customer base and so it became among the most successful of the ballrooms. It was a favourite haunt of powerful criminal figures including the boss of the Green Gang, Du Yuesheng. The Paramount (below) was Shanghai's largest and most famous ballroom, built on the instructions of a group of Chinese bankers in 1933, in an Art Deco style. Unlike many of it's rivals, the Paramount was a more complex venue, with a series of dance floors, bars and lounges, and, could accommodate over 1000 people. |

Below: 10 Cents scrip of c1940, payable at both ballrooms. |

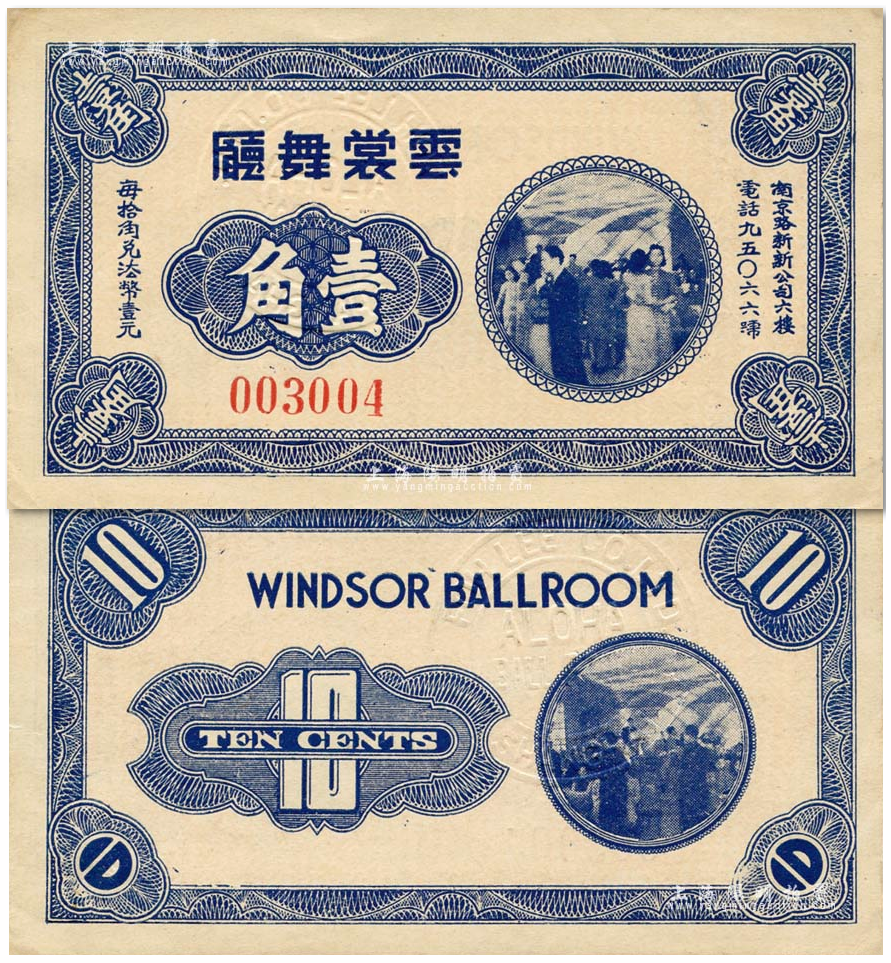

Windsor Ballroom

|

This establishment is something of a mystery as seemingly no reference can be found to it anywhere. At least two different 10 Cents scrip notes are known, of a similar design, though the other (not shown) carries some English text. This example (right) curiously has been marked with a circular embossed stamp for the Aloha Ballroom in Shanghai (1454 Avenue Edward VII). The only placename apparent in the Chinese/Japanese text is that of Nanking (Nanjing). |

Tuck Shun Chen Exchange

|

One of the numerous money changing businesses of pre-war Shanghai, located at 352 Canton Road. Right: a 20 coppers note depicting a Taoist God of Wealth. The date of 1916 may refer to the establishment of the business, as the note design is clearly based on that of currency issued by the Commercial Bank of China, from 1920 onwards. |

Shanghai City Temple Bazaar

|

Japanese occupation period scrip relating to the commercial district that was attached to the Temple of the City Gods in the Old City. The temple, which still stands and has been fully restored to use, commemorates the elevation of Shanghai to municipal status, and predates the 15th century. Right: Shanghai City Temple Bazaar 1 Dollar/Yuan of 1942. |

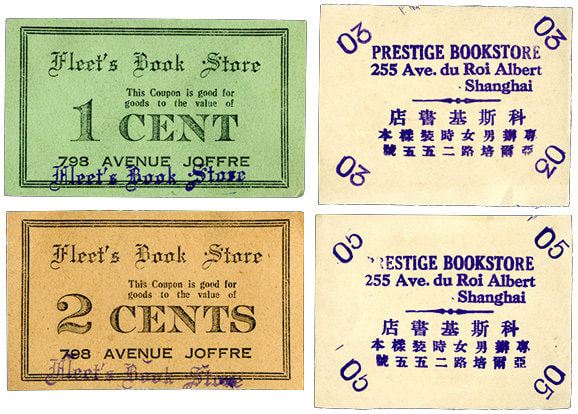

Bookshop tokens

Shanghai Central China Public Bus Company Limited

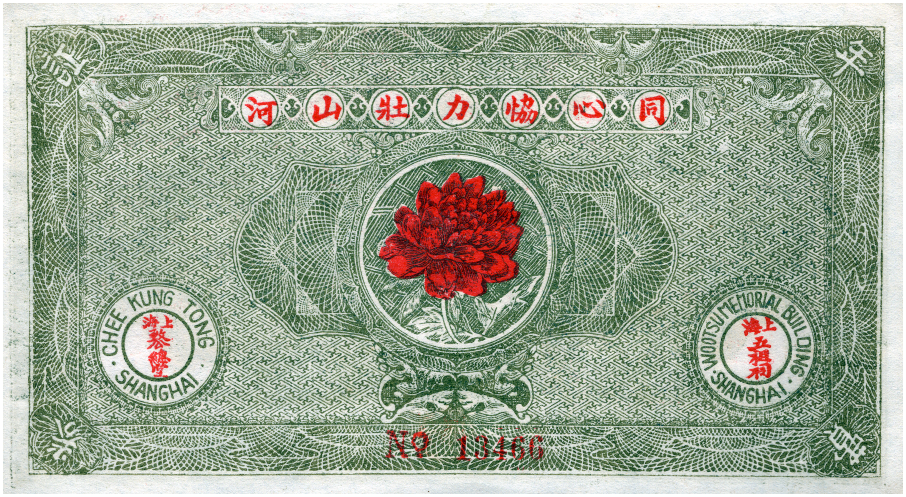

Chee Kung Tong 致公堂, Shanghai