|

December 20 2020

|

The Paper Money of Chee Kung Tong 致公堂, Shanghai

|

A study of an important and rare paper money issue from the Shanghai branch of the Chee Kung Tong (Zhì gōng dǎng), often referred to as Chinese Freemasonry, one of what are generally thought to be (though often erroneously) secret societies collectively known as the Hongmen. Many diverse groups including so-called "Chinese Freemasons" (no link to European based freemasonry), a political party, business groups and criminal gangs historically and currently identify as or trace their origins from the Hongmen and older organisations, such as the White Lotus Sect.

The sources used are Chinese and western, of various ages, and all are between them sometimes contradictory or impenetratable, for want of a better word. The information in this article is therefore not 'set in stone' but should however provide an informative and relatively reliable background. |

Only 3 examples of this note are known to exist among Chinese collectors, and I can only confirm one. A further small group recently appeared of these deceptively fascinating notes.

First, some background:

|

A History of the Tiandihui/Hongmen

The legendary origin of the Hongmen - Society of the Heaven and the Earth - is said to lie in the opposition which rose up against an early Qing (Manchu) emperor, some time after the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. The emperor (sometimes identified as Kangxi, 1654-1722) was in trouble due to a former tributary ruler and his people - the “Xi Lu” - who had rebelled and were now making incursions into Imperial territory. The emperor promised rewards to those who would fight and expel this threat from China, a challenge successfully taken up by the warrior monks of the Shaolin Monastery, though they refused any reward. However the emperor soon turned upon his saviours due to allegations by jealous courtiers that the monks were plotting against him. He reacted by burning the monastery, slaughtering the monks and sending soldiers to pursue those who escaped the carnage. |

Five of these surviving monks later gathered together and were said to have been joined by a scholar, Chen Jinnan, to found the Hongmen society (aka the Tiandihui) at the Red Peony Pavilion - purportedly for the purpose of overthrowing the Qing government (and some would later claim; restoring the Ming dynasty). Discovering an incense burner at the pavilion, the monks and their supporters swore an oath to Heaven that they would continue to recruit followers, then to return and perform a blood-oath, forming a bond of blood-brotherhood. Some accounts only record the blood brotherhood event as the founding ritual. This became the basis for membership of the Hongmen factions, and the central act of the initiation ritual.

The Historical Background

The Manchu captured Beijing in 1644 and established the Qing dynasty, relocating their capital there from Shenyang. Numerous sworn brotherhoods (jiebai xiongdi) - acting in open struggle rather than as secret societies - continued armed resistance against the invaders for a generation. Outlawed, these groups were small, independent, and without formal names, ceremonies or traditions.

The first phase in the development of Chinese secret societies is represented by rudimentary gatherings of small numbers of people during the Kangxi era (1662-1722). These societies, like the earlier sworn brotherhoods, were possibly inspired by the 'Romance of Three Kingdoms' (Sanguo yanyi), a 14th-century historical novel set in the late Han Dynasty and attributed to Luo Guanzhong and 'Outlaws of the Marsh' (Shuihuzhuan), better known in the West as the 'Water Margin', a 14th-century Chinese novel attributed to Shi Nai'an, both tales of rebellion against harsh and corrupt authority.

During the Yongzheng era (1723-1735), these brotherhoods gave way to societies known as hui, formed for the purpose of mutual aid. Still outlawed, they began to acquire formal names such as the Father-Mother Society. Only fifteen or sixteen such societies appear on archival records before 1755. Ming Restoration however was not mentioned in connection with any of them.

The strictly historical account places the foundation of the Tiandihui/Hongmen to have occurred in 1761 in the Fukien (Fujian) - Kwangtung (Guangdong) border area of South East China, by four men: a monk Ti Xi - also known as Hong Er, plus; Li Amin, Zhu Dingyuan, and Tao Yuan. The first recorded uprising was in 1767, though there was no obvious political motive.

Anti-Manchu rhetoric, slogans or confessions are seemingly absent from any uprisings throughout this period, as are any mention of Zheng Chenggong, or evidence of the Xi Lu, Shaolin Legend.

Groups continued to arise, leading rebellions but without any apparent motive beyond short term gain; three was a significant number among these groups - sometimes used in their names. As a result British and Chinese administrators from the mid 19th century onwards began referring to them as the Triads.

The first written evidence of Ming restorationism among any of these societies dates from 1800 when the phrase "Restore the Ming House" was part of an oath taken by members of Qiu Daqin's Tiandihui society in Kwangtung (Guangdong). In 1811 Huang Biao changed his name to Zhu Biao, claiming to be a scion of the Ming dynasty, but like earlier slogans, this was more a rallying cry than a goal. Ma Shaotang's 1831 poem: "When the red flag is unfurled, the heroes will come, sons of Heaven from outside will come to restore the Ming dynasty" had an emotional appeal but was not backed by any concrete programme.

The Manchu captured Beijing in 1644 and established the Qing dynasty, relocating their capital there from Shenyang. Numerous sworn brotherhoods (jiebai xiongdi) - acting in open struggle rather than as secret societies - continued armed resistance against the invaders for a generation. Outlawed, these groups were small, independent, and without formal names, ceremonies or traditions.

The first phase in the development of Chinese secret societies is represented by rudimentary gatherings of small numbers of people during the Kangxi era (1662-1722). These societies, like the earlier sworn brotherhoods, were possibly inspired by the 'Romance of Three Kingdoms' (Sanguo yanyi), a 14th-century historical novel set in the late Han Dynasty and attributed to Luo Guanzhong and 'Outlaws of the Marsh' (Shuihuzhuan), better known in the West as the 'Water Margin', a 14th-century Chinese novel attributed to Shi Nai'an, both tales of rebellion against harsh and corrupt authority.

During the Yongzheng era (1723-1735), these brotherhoods gave way to societies known as hui, formed for the purpose of mutual aid. Still outlawed, they began to acquire formal names such as the Father-Mother Society. Only fifteen or sixteen such societies appear on archival records before 1755. Ming Restoration however was not mentioned in connection with any of them.

The strictly historical account places the foundation of the Tiandihui/Hongmen to have occurred in 1761 in the Fukien (Fujian) - Kwangtung (Guangdong) border area of South East China, by four men: a monk Ti Xi - also known as Hong Er, plus; Li Amin, Zhu Dingyuan, and Tao Yuan. The first recorded uprising was in 1767, though there was no obvious political motive.

Anti-Manchu rhetoric, slogans or confessions are seemingly absent from any uprisings throughout this period, as are any mention of Zheng Chenggong, or evidence of the Xi Lu, Shaolin Legend.

Groups continued to arise, leading rebellions but without any apparent motive beyond short term gain; three was a significant number among these groups - sometimes used in their names. As a result British and Chinese administrators from the mid 19th century onwards began referring to them as the Triads.

The first written evidence of Ming restorationism among any of these societies dates from 1800 when the phrase "Restore the Ming House" was part of an oath taken by members of Qiu Daqin's Tiandihui society in Kwangtung (Guangdong). In 1811 Huang Biao changed his name to Zhu Biao, claiming to be a scion of the Ming dynasty, but like earlier slogans, this was more a rallying cry than a goal. Ma Shaotang's 1831 poem: "When the red flag is unfurled, the heroes will come, sons of Heaven from outside will come to restore the Ming dynasty" had an emotional appeal but was not backed by any concrete programme.

It was not until the late nineteenth century that a serious effort was undertaken to depict the Tiandihui as anti-Manchu. In 1903 Guangfu Hui member Tao Chengzhang (T'ao Ch'eng-chang) in his article "Jiaohui yuanliukao" linked the term Hong to the dynastic founder of the Ming, referring to his reign title Hongwu (1368-98). Tao was also the first to impute the society's founding to Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), also claiming Chen Jinnan as an earlier founder, although the name nowhere appears in the historical record. It was also Tao Chengzhang who divided the popular associations into northern White Lotus religious sects and northern secular Tiandihui.

Revolutionary and Kuomintang leader Sun Yat-sen became a Chee Kong Tong member and reorganiser. His 'Three Principles of the People' (1924) further elaborated on the anti-Manchu agenda attributed historically to the Hongmen. However he was neither a scholar nor historian and relied on the anecdotal evidence of society members. Dr. Sun and his fellow revolutionaries knew that they needed a rallying point for Chinese communities outside China and they intentionally rewrote the Tiandihui history to that purpose. To use the Hongmen, Dr. Sun needed to create an anti-Manchu consciousness by endowing the society with a revolutionary pedigree - contrary to the Xi Lu Legend which was anti-government, but not specifically anti-Manchu. The revolutionaries portrayed the Tiandihui as a key element in early Chinese resistance against the Manchus, a romanticized perception that persists to this day.

Revolutionary and Kuomintang leader Sun Yat-sen became a Chee Kong Tong member and reorganiser. His 'Three Principles of the People' (1924) further elaborated on the anti-Manchu agenda attributed historically to the Hongmen. However he was neither a scholar nor historian and relied on the anecdotal evidence of society members. Dr. Sun and his fellow revolutionaries knew that they needed a rallying point for Chinese communities outside China and they intentionally rewrote the Tiandihui history to that purpose. To use the Hongmen, Dr. Sun needed to create an anti-Manchu consciousness by endowing the society with a revolutionary pedigree - contrary to the Xi Lu Legend which was anti-government, but not specifically anti-Manchu. The revolutionaries portrayed the Tiandihui as a key element in early Chinese resistance against the Manchus, a romanticized perception that persists to this day.

|

Right: Sun Yatsen (distinctively seated centre-right) at the opening ceremony for the National Relief Bureau in San Francisco, July 1911.

In the front row, (from right) are Huang Yun-su, Li Shi-nan, Zhao Yu (seated immeditaely below Sun Yatsen), Wu Ping-yi and Zhang Ai-yun. Zhao Yu was later the head of the Chee Kung Tong at Shanghai. |

The Chee Kong Tong emerged in the mid 19th century, with branches formed by Chinese communities overseas, including the United States, Canada, Mexico, the UK and Australia. Numerous different Tongs were formed in San Francisco; the Chee Kong Tong (CKT) established here in 1849 is said to have origins in Kwangtung (Guangdong) Province, China, and seems often to be regarded as the origin of some or all of the CKT.

The organisation was allied with and supportive of Sun Yatsen who is reported to have joined in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1904, and to have held a senior position either there or in San Francisco. "While rallying for assistance from overseas Chinese living mainly in North America and in Europe, he utilized the Chee Kong Tong to publicize the work of his Republican Party in the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty." Chee Kong Tong members provided much of his funding. There was however a split between them, around the time of 1911 revolution, and further conflict between CKT and the Kuomintang (Guomindang) during the 1920s inside and outside of China which partly concerned the latters ties with the Soviet Union.

|

The Chee Kong Tong at Shanghai was established in September 1925 at a three-storey western-style residential building of a brick and wood structure at No. 860 Huashan Road (No. 476 Avenue Haig before 1950). It seems the building in question has since been demolished, in 1993. The decision to construct the Chee Kong Tong Five Ancestral Temple at Shanghai was reportedly made at a major Hongmen conference held in San Francisco, USA in 1923. The stated purpose was to commemorate the legendary Five Ancestors of the Hongmen, and to become a global liaison base. $10 million was raised for the project. The 2 yuan notes were issued within a year of the temple's inaugaration. |

In Mainland China, the CKT is now known as the (China) Zhi Gong Party 中国致公党 (Zhōngguó Zhìgōngdǎng), a political party that participates in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. The party was established in October 1925, out of San Francisco, and the newly created Shanghai branch. Sun Yatsen's former ally and now rival Chen Jiongming was elected titular head. The headquarters of the party was based in Hong Kong from 1926. ln 1927 Chen made public his "Principle of Three Constructions", which advocated achieving world peace through formation of a federation of world states proceeding in three stages. In 1931 Chen proposed a program of "Chinese Socialism." At least one source states however that the party didn't move to the political left until 1947, becoming an ally of the Chinese Communist Party.

The party become involved in protests and boycotts against the Japanese following their invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

In 1949, the CKT party was invited to participate in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and the formation of the new government of the Peoples Republic of China following the revolution. The CPPCC was succeeded by the National People's Congress (parliament) in 1954. The CKT continues to be one of the 8 officially recognised minor parties in the Chinese parliament, holding 38 seats, plus 3 on the Standing Committee of the NPC.

The Paper money issue:

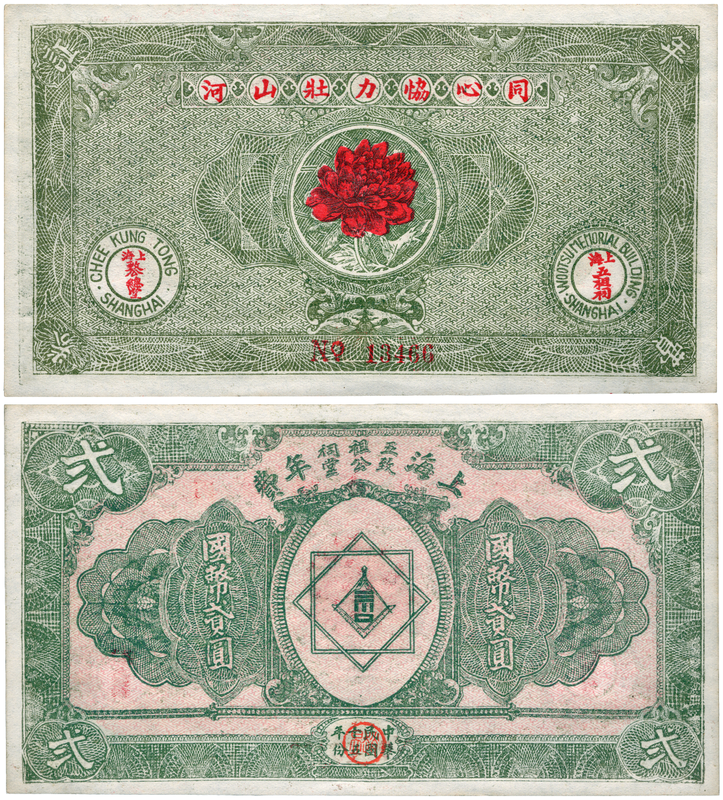

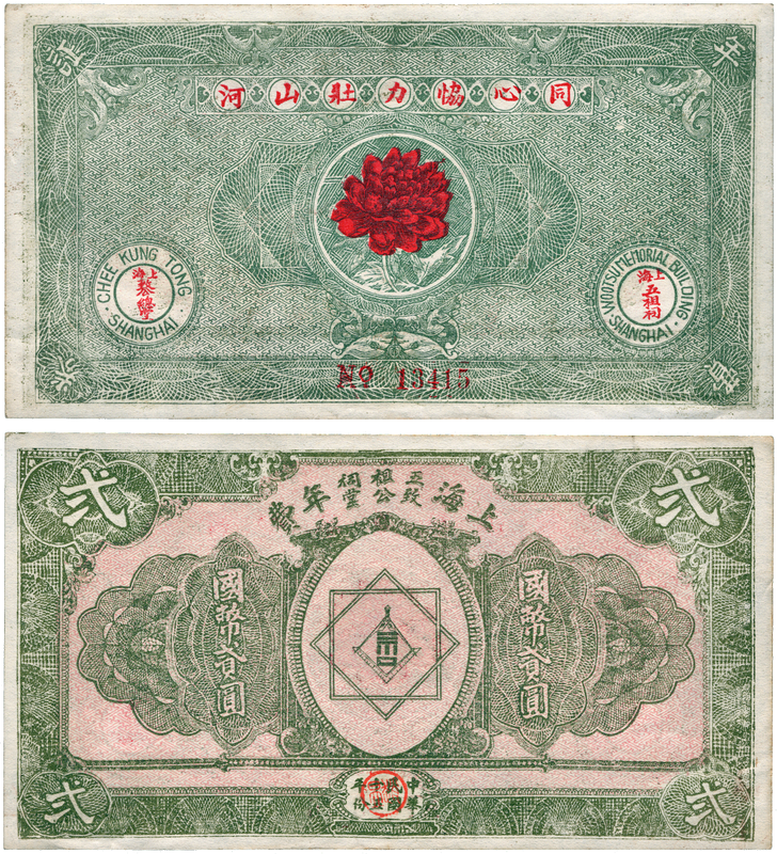

2 Yuan - 弍 - 貳圆

A 2 Yuan National Currency (圓貳幣國) note/certificate dated 1926 (中華民國十五年份).

This is the only known currency issue by this organisation. That said, its status as paper money is questionable as it appears to be more a form of certificate disguised as paper money?

Curiously, two different versions of the 'financial' character for '2' are used.

At least one Chinese source considers the side of the note depicting the central star with the 2 denomination at the four corners as the "front" of the note, however as this isn't clear I'm choosing to consider the side depicting the central red flower as the front but only for the descriptive purposes of this article. Arguments can be made for either.

The note is printed in green and red on the 'front'. Green with red-pink underprint on the 'back'.

The printer (no doubt a local Shanghai business) is unknown.

A 2 Yuan National Currency (圓貳幣國) note/certificate dated 1926 (中華民國十五年份).

This is the only known currency issue by this organisation. That said, its status as paper money is questionable as it appears to be more a form of certificate disguised as paper money?

Curiously, two different versions of the 'financial' character for '2' are used.

At least one Chinese source considers the side of the note depicting the central star with the 2 denomination at the four corners as the "front" of the note, however as this isn't clear I'm choosing to consider the side depicting the central red flower as the front but only for the descriptive purposes of this article. Arguments can be made for either.

The note is printed in green and red on the 'front'. Green with red-pink underprint on the 'back'.

The printer (no doubt a local Shanghai business) is unknown.

|

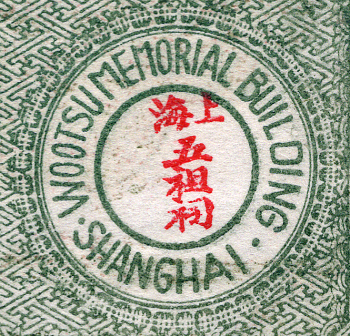

Front:

The central design is of a red flower (details below) with a seven character inscription in red above, a slogan: 同心協力壯山河 which seems to translate as "Working Together to Strengthen the Mountains and Rivers" (the Nation?) A real 5 digit serial number in red appears in the lower border of the front. At the lower left is a circular cartouche with an outer ring of text in English; “Chee Kung Tong - Shanghai” and an inner circle containing 上海 for Shanghai, and two further as yet unidentified characters beneath, all in red. The matching cartouche at the lower right of the front again carries an outer text ring in English; “Wootsu Memorial Buildings - Shanghai”. This was the location of this then new Shanghai Hongmen. The inner circle again contains the red Chinese characters for Shanghai and a further three characters below: 五祖祠 which translates literally as the Five Ancestors or patriarchs - a reference to the Hongmens legendary five founding Shaolin monks. |

A character appears in each corner:

Upper right: 年, annual, year Lower right: 費, fee, expenses

Upper left: 証, prove, confirm, verify Lower left: 券, deed; bond; contract; ticket

Which seems to indicate that this note was to certify the payment of an annual fee?

Upper right: 年, annual, year Lower right: 費, fee, expenses

Upper left: 証, prove, confirm, verify Lower left: 券, deed; bond; contract; ticket

Which seems to indicate that this note was to certify the payment of an annual fee?

|

The central vignette of a red flower

This is a peony: ‘paeonia suffruticosa’. This would be a logical enough identification. The peony was once an official emblem of China, and it plays a major role in many holidays and religious traditions. It is the flower with the longest continual use in Eastern culture, and is tied in with concepts of honour in those societies. The peony is sometimes known as 富貴花 (fùguìhuā) "flower of riches and honour" or 花王 (huawang) "king of the flowers" The colour of the flower: red is most prized in China and Japan, and has the strongest ties to honour and respect. It is the colour most symbolic of wealth and prosperity (good luck) in both cultures, especially China. There is a Cantonese opera known as ‘The Legend of the Red Peony’. Robin Leung (a stage actor who moved to Canada from Hong Kong in 1972), has explained that the opera; |

“....is a fairy tale about Empress Wu Zhe Tian. Wandering around her garden during the winter, the empress ordered all the flowers to bloom, but the red peony did not. A young handsome scholar falls in love with the red peony flower fairy and begs a goddess to save her.

The goddess gives him a magic potion with which he saves the flower, and they live happily ever after.

“Cantonese operas always have happy endings. It gave people hope during unstable times when life was tough. Do your good deeds and you will be rewarded – God will help you,” says Leung.

The goddess gives him a magic potion with which he saves the flower, and they live happily ever after.

“Cantonese operas always have happy endings. It gave people hope during unstable times when life was tough. Do your good deeds and you will be rewarded – God will help you,” says Leung.

The Historical roots of Cantonese Opera

In 1644, Leung says, when Manchurians entered Beijing, many Han Chinese did not like the changes they made, causing a revolutionary atmosphere. Many Cantonese opera costumes come from the Ming dynasty, the one previous to Manchurian (Qing) rule.

The Qing government, a Manchurian government, forced Cantonese operas to stop performing, leading many of its members to escape overseas.

“Opera troupes were often hiding places for revolutionists, specifically Chinese Free Mason or secret society members, who were fleeing from the government. They brought Cantonese opera to North America,” says Leung."

(Source: http://thelasource.com/en/2015/04/13/cantonese-opera-tells-the-tale-of-the-red-peony/ )

Most importantly, the use of the red peony is clearly a direct reference to the legendary mid 17th century founding of the society by the five monks, their leader and supporters in a ritual at the Red Peony Pavilion, as described in the opening paragraphs above.

|

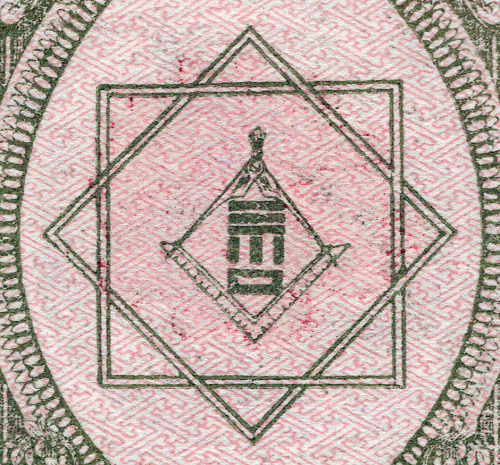

Back: A central image of two squares forming a star. In Chinese tradition, the eight pointed star is said to be a way to concisely depict the Universe. The number eight is also famously regarded as the luckiest number by many Chinese people, symbolising prosperity. This star frames a form of the well known masonic emblem of a conjoined set-square and compass, within a larger frame/cartouche. At the very centre, the unusual symbol of lines and a rectangle apparently represents a "hidden number" of the Hongmen? The 'denomination' of 2 yuan in National Currency is given in flanking columns of four Chinese characters (圓貳幣國). Above this is a title of 10 characters, from right to left: 上海, Shanghai 五祖祠 - 致公堂, Five Ancestor Temple - Chee Kung Tong (Zhi Gongtang) 年費, annual fee |

Large denomination characters for '2' 弍 appear in each corner, in a different form to that given each side of the masonic symbols at centre.

The cartouche in the lower border contains the date, overstamped with a red circular seal containing two characters, a name, written in seal script 趙昱. This is Zhao Yu, who was then the head of the Shanghai Chee Kung Tong, and deputy leader of the CKT political party. During the Chinese revolution of 1911 he had closely worked with Sun Yatsen and fundraised extensively collecting over 140,000 yuan for the revolution. He left the party in the late 1940s, and effectively vanished. His date of death remains unknown.

Below: a second example in slightly different shades of green.

The cartouche in the lower border contains the date, overstamped with a red circular seal containing two characters, a name, written in seal script 趙昱. This is Zhao Yu, who was then the head of the Shanghai Chee Kung Tong, and deputy leader of the CKT political party. During the Chinese revolution of 1911 he had closely worked with Sun Yatsen and fundraised extensively collecting over 140,000 yuan for the revolution. He left the party in the late 1940s, and effectively vanished. His date of death remains unknown.

Below: a second example in slightly different shades of green.

Sources include -

Initiation: Ritual Drama and Secret Knowledge Across the World (Themes in Social Anthropology, Vol 3) 25 Apr 1986

by J. S. La Fontaine, p42-43.

The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History. Murray, Dian (1994). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 16–17.

Red Turbans in the Trinity Alps: Violence, Popular Religion, and Diasporic Memory in Nineteenth Century Chinese America. Robert G. Lee.

"Deciphering Hongmen's two-yuan coupons..." An article by 陈耀光 (Chen Yaoguang) published by the Macau Numismatic Society in 2016: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4bcfd3310102wvr9.html

Entry Denied - Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943. Edited by Sucheng Chan. Temple University press, Philadelphia. Chapter 6, p171-212 by Him Mark Lai.

http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/history/chinese_freemasons/index.html

Initiation: Ritual Drama and Secret Knowledge Across the World (Themes in Social Anthropology, Vol 3) 25 Apr 1986

by J. S. La Fontaine, p42-43.

The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History. Murray, Dian (1994). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 16–17.

Red Turbans in the Trinity Alps: Violence, Popular Religion, and Diasporic Memory in Nineteenth Century Chinese America. Robert G. Lee.

"Deciphering Hongmen's two-yuan coupons..." An article by 陈耀光 (Chen Yaoguang) published by the Macau Numismatic Society in 2016: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4bcfd3310102wvr9.html

Entry Denied - Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943. Edited by Sucheng Chan. Temple University press, Philadelphia. Chapter 6, p171-212 by Him Mark Lai.

http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/history/chinese_freemasons/index.html

Fin.