|

July 03, 2019

|

Rude Confucius - the Sabotage of Japanese Puppet Currency

A study of the attempt to ridicule and undermine the wartime Japanese puppet regime in Northern China through the sabotage of the early currency of its bank; the Federal Reserve Bank of China. Related issues are also covered: the early currency of the Hua Hsing Bank based in Shanghai, and a scarce series of insurance stamps for Northern China.

|

Above: Wang Shizhen, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of China, in 1938

|

The Japanese organised their Provisional Government of the Republic of China following the capture of Peking/Peiping and surrounding regions from July 1937, commencing with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. The government was officially inaugurated by Wang Kemin, the former Kuomintang Minister of Finance and Shanghai banker, on 14 December 1937, with its capital at Peking (Beijing). The Federal Reserve Bank of China (FRB) was established March 10th 1938, with the former manager of the Shenyang branch of the Bank of China, Wang Jing When (Wang Shizen) appointed president of the bank (and also Finance Minister). The bank is sometimes also referred to as the Federated Reserve Bank of China or the United Reserve Bank of China.

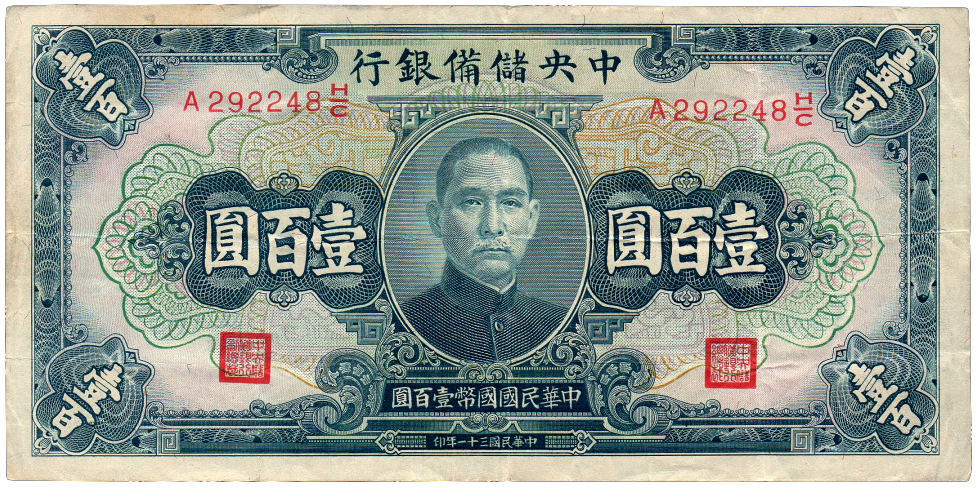

The government lacked substantial authority and was not recognised by any government offically, not even by the government of Japan. In March 1940 it was merged with other puppet regimes and territories to form the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China led by Wang Jingwei, and based at Nanking (Nanjing). However in most respects, the now renamed Peking based regime, operating as the "North China Political Council" (華北政務委員會) maintained control of the north, and the Federal Reserve Bank of China continued to issue currency until the end of the war. |

|

The ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius (551-479 BCE) was still highly regarded both by the Chinese Nationalists and by factions within Imperial Japan, despite a period of neglect and even suppression in the latter following the Meiji restoration of 1868. By the 1930s, core components of Confucianism were being selected and distorted by such as the philosopher Inoue Tetsujirō (1856-1944) for nationalistic and imperialistic purposes, to encourage loyalty to the state and the notion of self-sacrifice in its promotion and defence. This would have long lasting and negative consequences for Confucianism in Japan after defeat in 1945. Japan occupied Kufow (Qufu), and much of the rest of Shantung (Shandong) province, from late 1937 until 1945. Kufow was and is the location of the tomb of Confucius, the Confucian family cemetery, primary temple and family mansion. The supposed descendants of Confucius who had resided in the Estate complex since the 14th century, escaped to Chungking (Chongqing), the wartime capital of Nationalist China. Japanese news reports of the period falsely claimed that the family had been kidnapped by the Nationalists. Right: an article of January 1938 which appeared in Japanese-English newspaper Nippu Jiji (later renamed the Hawaii Times), tries to present the Japanese occupation of Kufow in a positive light. As the occupation of large regions of China progressed, the Japanese sought to remove elements of Kuomintang influence. This included such as removing imagery associated with the Chungking regime of Chiang Kai-shek and nationalist China. One such example was the public portraits of the late leader and revolutionary founder of the Republic, Dr Sun Yatsen: |

|

"Not content with the substitution of the portrait of Confucius for that of Sun Yat-sen in the schools, the Government has recently issued another thousand of these portraits to make sure that nobody (re)introduces the picture of the more modern Sage on the plea that the portrait of Confucius has been worn out or "is missing." (Oriental Affairs: A Monthly Review - Volumes 11-12 - Page 494, 1939)

|

|

As with the public portraits, Japan initially sought to replace the currency mostly emblazoned with the portrait of Sun Yatsen with new notes issued by their puppet banks, carrying (in theory) more acceptable portraits and vignettes which they clearly felt were less connected with the Kuomintang regime. However such would need to still be 'Chinese' enough to encourage public acceptance of the notes; a scheme which rapidly proved to be a failure. Furthermore, the tactic later would be to return Sun Yatsen to the money, through the issues of the Nanking based Central Reserve Bank of China.

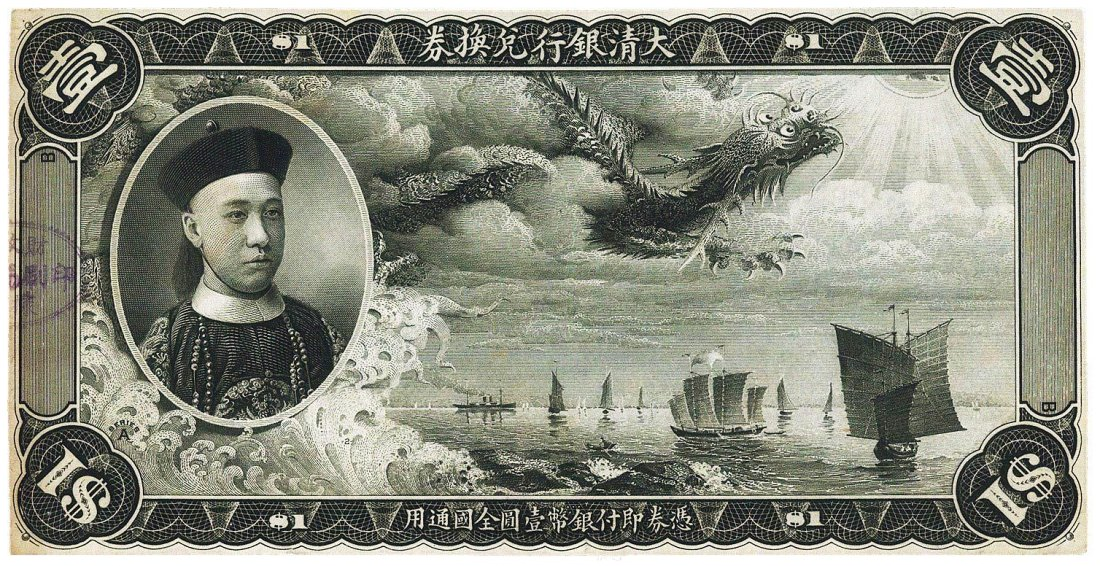

The Japanese presumably chose the general theme for the portraits of the new currency issues, which in the case of the FRB notes would appear on adaptations of designs originally produced for the Qing dynasty's Ta Ching Government Bank. This series and other issues from this period would depict significant figures from Chinese history and mythology, some of whom were revered in Japan too: Confucius, Yue Fei, Guan Yu, and Huangdi. Much of the process of design, production and distribution was clearly left to the occupied Chinese, judging by the long failure of the Japanese to detect the sabotage. Right: c1930 photo of the original statue of Confucius which stood in the Dacheng Hall of the temple of Confucius at Kufow (Qufu) until its destruction in 1966. |

The currency and stamps

It seems that the large-size Federal Reserve notes with Confucius (and all) came first in 1938, followed by the unissued(?) Hua Hsing Bank series of 1939 which was partially lost at sea and cancelled - either due to the loss or the discovery of the sabotage to the design. That said, insurance stamps were issued in 1940 with what would be the last use of the designs. The smaller sized Federal Reserve notes which reverse the portraits were produced either before or alongside the Hua Hsing series, in 1939.

All four Confucius portraits employed across the three different banknote issues plus the insurance stamp are slightly different to each other in various ways, though they can be in a sense paired. For example; curiously, the small sized Federal Reserve note portrait is not a mirror image of that used on the larger issue, but is clearly based on the portrait of the Hua Hsing note. It's not just that the portraits face the same way but that they share details such as the v-neck effect of the robes as they appear beneath Confucius's beard. Equally, the 1940 insurance stamp portrait, despite being the last appearance of 'Rude Confucius', is clearly copied from its first appearance, on the large sized note (see images below).

The Confucius portraits, which depict the sage making an obscene gesture with his fingers, are the clearest example of this anti-Japanese sabotage. However, perhaps the entire series of the Federal Reserve Bank of China is in some way part of this scheme, depending on who selected which historical/mythical figures to represent. The depiction of mythical and historical figures is unusual on Chinese currency - even the God(s) of Wealth usually only appear in a limited form, such as the red overprints often found on small commercial note issues. One exception being a slightly more prominent appearance on the currency of the Commercial Bank of China. Secondly, these figures - especially Huangdi, the mythical founder of the Chinese people and civilisation (on the 100 dollars/yuan) and Yue Fei, a loyal warrior general who was betrayed; were quite prominently used in the propaganda of Chinese Nationalism (ie: the Kuomintang).

All four Confucius portraits employed across the three different banknote issues plus the insurance stamp are slightly different to each other in various ways, though they can be in a sense paired. For example; curiously, the small sized Federal Reserve note portrait is not a mirror image of that used on the larger issue, but is clearly based on the portrait of the Hua Hsing note. It's not just that the portraits face the same way but that they share details such as the v-neck effect of the robes as they appear beneath Confucius's beard. Equally, the 1940 insurance stamp portrait, despite being the last appearance of 'Rude Confucius', is clearly copied from its first appearance, on the large sized note (see images below).

The Confucius portraits, which depict the sage making an obscene gesture with his fingers, are the clearest example of this anti-Japanese sabotage. However, perhaps the entire series of the Federal Reserve Bank of China is in some way part of this scheme, depending on who selected which historical/mythical figures to represent. The depiction of mythical and historical figures is unusual on Chinese currency - even the God(s) of Wealth usually only appear in a limited form, such as the red overprints often found on small commercial note issues. One exception being a slightly more prominent appearance on the currency of the Commercial Bank of China. Secondly, these figures - especially Huangdi, the mythical founder of the Chinese people and civilisation (on the 100 dollars/yuan) and Yue Fei, a loyal warrior general who was betrayed; were quite prominently used in the propaganda of Chinese Nationalism (ie: the Kuomintang).

|

1) The large size FRB $1 of 1938 (SCWPM J54)

|

2) Hua Hsing Commercial Bank 10 Yuan ND (1939) Pick J99s

|

1) The small size FRB $1 of 1938 (SCWPM J61)

|

4) The North China Postal life insurance stamps of 1940

|

The Federal Reserve Bank of China - 中国聯合準備銀行

The large-size notes of the 1938 series use the engravings originally produced for a series of notes for the Ta Ching Imperial Government Bank by American designers/engravers; Lorenzo J. Hatch (1857-1914) and William A. Grant (1868-1954).

A periodical known as 'The Billboard' carried an article on currency manipulation and forgery (pages 70-71 February 20th, 1943) "One of the first acts of the Japanese invaders was to seize a Chinese engraver who had been employed in the Peking engraving bureau (Bureau of Engraving and Printing Peking). They forced him to engrave plates for counterfeit (puppet) Chinese one yuan currency notes" and then the article continues to relate how he engraved the portrait (of Confucius) to show him making an obscene gesture. There seems to be some confusion in the article regarding the circumstances. The article then mysteriously states that 50,000 of these notes were first circulated in Shanghai to the amusement of the public and "chagrin" of the bankers before being withdrawn, and that later they were re-issued in the North-East (the article states Manchukuo but this is surely a mistake - as possibly much of this article is?) It is possible that the 50,000 notes referred to is actually a confusion with the Confucius issue of the Hua Hsing Commercial Bank at Shanghai (see below); if nothing else, this may at least indicate that some of those notes made it into circulation? The article also states that the engraver escaped and fled to join Chiang Kai-shek in Chungking.

In another version: "It is claimed that the man responsible for the portrait was a famous Peking artist who shocked many by agreeing to work for the Japanese. They heavily publicised his participation for months and then suddenly he disappeared. According to the story he quietly entered the British Concession at Tientsin and left for Hong Kong and went into hiding. Soon after the Japanese discovered the meaning of the gesture upon the two series of notes by which time millions were already circulating."

A periodical known as 'The Billboard' carried an article on currency manipulation and forgery (pages 70-71 February 20th, 1943) "One of the first acts of the Japanese invaders was to seize a Chinese engraver who had been employed in the Peking engraving bureau (Bureau of Engraving and Printing Peking). They forced him to engrave plates for counterfeit (puppet) Chinese one yuan currency notes" and then the article continues to relate how he engraved the portrait (of Confucius) to show him making an obscene gesture. There seems to be some confusion in the article regarding the circumstances. The article then mysteriously states that 50,000 of these notes were first circulated in Shanghai to the amusement of the public and "chagrin" of the bankers before being withdrawn, and that later they were re-issued in the North-East (the article states Manchukuo but this is surely a mistake - as possibly much of this article is?) It is possible that the 50,000 notes referred to is actually a confusion with the Confucius issue of the Hua Hsing Commercial Bank at Shanghai (see below); if nothing else, this may at least indicate that some of those notes made it into circulation? The article also states that the engraver escaped and fled to join Chiang Kai-shek in Chungking.

In another version: "It is claimed that the man responsible for the portrait was a famous Peking artist who shocked many by agreeing to work for the Japanese. They heavily publicised his participation for months and then suddenly he disappeared. According to the story he quietly entered the British Concession at Tientsin and left for Hong Kong and went into hiding. Soon after the Japanese discovered the meaning of the gesture upon the two series of notes by which time millions were already circulating."

|

Life Magazine of October 9 1944 mentions these notes on page 13; that the Japanese had withdrawn them and placed "a price on the engravers head". It is not known as to when exactly the Japanese authorities discovered the sabotage of Confucius's portraits, though it presumably had to be between mid 1940, and early 1941. During this period, the replacement series was introduced by the FRB, and the insurance stamp series was seemingly scrapped. An interesting possibility (left) may be the revival of the annual festival honoring Confucius, held at the principle temple and his tomb at Kufow (Qufu). This had not been held since 1936 due to the Japanese invasion. This much promoted event in September 1940 was attended by officials both from the Northern China government which operated the issuing bank, and from the Nanking puppet regime. Perhaps it was during this event that the truth was revealed. |

|

Right: Federal Reserve Bank of China $1 of 1938 (SCWPM J54, Smith & Matravers C286-10). A small security mark, the character 中 is located on one of the waves at the lower right of the portrait, towards the border. 'Rude' Confucius faces right, in the place of Prince Chun on the original Ta Ching Bank designs. A dragon sweeps across the sky. In traditional Chinese culture, dragons have long been associated with benevolence and fertility, as a being who brought rain to the people. They have also come to symbolize strength, protection, happiness and goodness. Long a symbol of Imperial power, the five clawed dragon as shown here became the exclusive symbol of the emperor from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) onwards. Printed by the Bureau of Engraving & Printing at Peking (Beijing) 北京印刷局 |

|

Right: Federal Reserve Bank of China 1 yuan of 1938 (SCWPM J61, Smith & Matravers C286-12). Printed by the Executive Committee, Japanese Government Cabinet Office Printing Bureau - 行政委员会印刷局印 The building depicted on the back is the ancient 8 sided pagoda of Tianning Temple, Peking (Beijing), built during the Liao Dynasty, c1100 to 1119 CE. Though generally thought of as the smaller version of SCWPM J54 (etc), the notes of this series are almost entirely new. The only truly original feature carried over from the earlier notes 'as is' appears to be the dragon. |

Hua-Hsing Commercial Bank 華興商業銀行

Hua Hsing (pronounced Wha Shing) Commercial Bank was formally opened on May 16, 1939 in the Hongkew district of Shanghai, by the Japanese- sponsored "Reformed Government of China" at Nanking. It was a joint venture between the puppet regime and six Japanese banks. It ceased issuing currency by 1941.

The notes were apparently engraved and printed in Japan judging by the style of the notes and altogether cancelled - either due to the loss of the 10 yuan at sea, or less likely the discovery of the sabotage to the design.

The notes were apparently engraved and printed in Japan judging by the style of the notes and altogether cancelled - either due to the loss of the 10 yuan at sea, or less likely the discovery of the sabotage to the design.

|

Right: Hua Hsing Commercial Bank 10 Yuan ND (1939) Pick J99s, S/M H184-13s Confucius is depicted at right, making the infamous gesture. One apparently unremarked feature not found on the other versions of this portrait, is that Confucius is depicted with a large gap between his visible, protruding teeth. In some cultures this is considered a sign of good luck. In Chinese tradition teeth can symbolise prosperity, and a gap is considered to be a sign of excessive generosity - or wastefullness. Confucius was described in early accounts and sometimes depicted in various historic images as having buck teeth. Though both the small and large Federal Reserve note issues utilise versions of this portrait, the Hua Hsing version is of a higher quality, and appears - along with the rest of the design - to be by the same engraver as produced the dragon emblazoned military series (eg: SCWPM M19), the later Manchukuo (eg: SCWPM J130) and the Korea notes. The building depicted at left is the Dacheng Hall of the Temple of Confucius, Chefoo (Qufu), Shantung (Shandong) province. As described in the link, Chefoo is the site of the Confucius family estate, the primary temple, and tomb of Confucius. |

|

Right: Hua Hsing Commercial Bank 10 Yuan ND (1939) Pick J99a, S/M H184-13. The entirety of this Hua Hsing 10 yuan issue of 1939 was lost at sea. Other than the even more rare specimen examples above, none of the issued notes are known to have survived intact, all having been salvaged in recent decades, and hence clearly showing signs of long term water damage. On this example, the red ink used on the seals and serials has been effected the most with only the faintist traces discernable. The block letter 4 is just visible beneath the temple building. |

|

Right: Hua Hsing Commercial Bank 5 Yuan ND (1939) Pick J97s, S/M H184-11s Yue Fei is depicted at right. As with the Confucius portrait, it seems that the Yue Fei portrait used on the small-size 5 yuan of the Federal Reserve Bank of China is based on that used here (or both share the same source), and not on the portrait used on the larger FRB note. As noted in the introduction, the choice of Yue Fei as a subject for portrayal, exclusively, on issues of Japanese puppet banks is odd. This renowned warrior was famous for his loyalty and his defence of China from invaders! One of his most famous quotes was huán wǒ hé shān; literally "return my rivers and mountains", or "return my territory". This appeared on Nationalist Chinese propaganda of the time. This peculiar choice may be another, albeit less obvious example of anti-Japanese sabotage by the artist/designer also responsible for the 'vulgar wise-man' portrait of Confucius. The Liuhe Pagoda of Hangchow (Hangzhou) is depicted at left. The pagoda was reconstructed during Yue Fei's lifetime, and the general himself (d.1141) is buried nearby. The multicolour underprint used on this note in particular is very reminiscent of those used on various issues of the puppet Central Reserve Bank of China, especially the 100 yuan of 1942, SCWPM J14 (right) |

North China Postal Life Insurance - 華北郵政人壽保險

|

Right: a selection of stamps issued in 1940 for a life insurance scheme apparently operated by the North China postal department of the Japanese puppet government. There are at least 11 denominations ranging from 1 yuan to 500 yuan. The portraits of Confucius and Guan Yu are based on the versions of those used for the original large-size Federal Reserve banknotes. The third portrait may be of the philosopher Mencius? That very few seem to survive may indicate that the true nature of the portrait was discovered shortly after the issue of these stamps? |

Fin.