Peking - Beijing - 北京 |

New Created September 26 2018

|

Peiping - Beiping - 北平

Section 1: An Introduction to Peking

|

Peking, now referred to by the romanised name and pronunciation Beijing, is the current capital of the People's Republic of China. The city has had numerous different names during its 3000 year history, and has served as a capital under many different states and regimes, being destroyed and rebuilt frequently. Some of the oldest surviving structures in the city date to the 12th century, such as the Tianning Temple. Modern humans have occupied the region for at least the last 27,000 years.

Named Khanbaliq or Dadu, Beijing was the capital of the Yuan dynasty of the Mongol Empire founded by Kublai Khan, from 1271 until the triumph of the Ming in 1368. |

The name Beijing (meaning 'Northern Capital') was first adopted in 1403, and in 1420 it became formally the capital of the Ming Dynasty. Many of the city's most significant structures were established during this period including the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven. The city flourished and was for most of the 15th-18th centuries, the largest city on Earth.

Beijing continued as the capital throughout the Ming and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, and as the capital of the new Republic of China under the Beiyang Government from 1912 until it's defeat in 1927-28 under Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang party.

The seat of government then moved to Nanjing in 1928, which had been the intended location of the capital following the 1911 Revolution. During 1928-1949, the city was known as Peiping (Beiping) to reflect it's lesser status. The capital only returned to Beijing following the victory of Chairman Mao and the Communist Party in 1949.

Beijing continued as the capital throughout the Ming and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, and as the capital of the new Republic of China under the Beiyang Government from 1912 until it's defeat in 1927-28 under Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang party.

The seat of government then moved to Nanjing in 1928, which had been the intended location of the capital following the 1911 Revolution. During 1928-1949, the city was known as Peiping (Beiping) to reflect it's lesser status. The capital only returned to Beijing following the victory of Chairman Mao and the Communist Party in 1949.

Above: the Deshengmen (gate) and moat, c1900. Photographer unidentified.

The Late Qing Dynasty

During the Second Opium War, Anglo-French forces captured the outskirts of Beijing, looting and burning the Old Summer Palace in 1860. Under the Convention of Peking ending that war, Western powers for the first time secured the right to establish permanent diplomatic, colonial, presences within the city. In 1900, the attempt by the "Boxers" to eradicate this presence, as well as Chinese Christian converts, led to Beijing's reoccupation by foreign powers.

The Xinhai Revolution erupted in October 1911 and ended with the abdication of the six-year-old Last Emperor, Puyi, on 12 February 1912. Except for a couple of brief and failed revivals in 1915 and 1917, this marked the end of over 2000 years of imperial rule.

During the Second Opium War, Anglo-French forces captured the outskirts of Beijing, looting and burning the Old Summer Palace in 1860. Under the Convention of Peking ending that war, Western powers for the first time secured the right to establish permanent diplomatic, colonial, presences within the city. In 1900, the attempt by the "Boxers" to eradicate this presence, as well as Chinese Christian converts, led to Beijing's reoccupation by foreign powers.

The Xinhai Revolution erupted in October 1911 and ended with the abdication of the six-year-old Last Emperor, Puyi, on 12 February 1912. Except for a couple of brief and failed revivals in 1915 and 1917, this marked the end of over 2000 years of imperial rule.

|

The Republic (1912-1949)

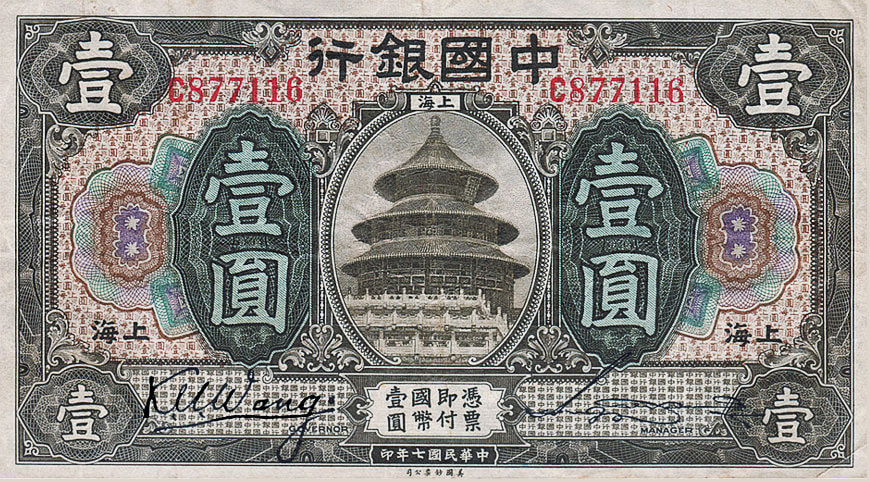

The intention following the Revolution had been to break the government away from the long-time seat of Qing imperial power and move the capital to the more central and sometime former capital of Nanking (Nanjing). However the warlord and ex-imperial politician Yuan Shikai manipulated his way into control as the first formal President of the Republic, and kept the capital at Beijing. That in 1915 he declared himself the Hongxian Emperor (12 December 1915 – 22 March 1916) is with hindsight at least no surprise. Following mass uprisings in response to the return of imperial rule, he abdicated and returned to his role as President, but died within months. Beijing then fell under the control of a succession of warlords and weak presidents, until the government was finally overthrown in 1927 by Chiang Kai-shek and the Guomindang (Kuomintang). The subsequent demotion of the city following the movement of the capital to Nanking caused numerous changes, and not just politically. Some that might be expected did not occur immediately: foreign diplomats remained in Beijing until the mid 1930s; the British for instance only upgraded their legation to that of a full embassy in 1935, moving it to Nanking during 1936-1937. With Beijing's change in status, the headquarters of the government and other major banks were relocated to Shanghai, with the city's government bank offices even ceasing to be the regional branch of issue, which from the late 1920s was at the nearby port city of Tientsin (Tianjin). This explains why some banknotes of the Bank of China are found with the Peking placename crossed out and overprinted with 'Tientsin'. After the late 1920s comparitively few banknotes are issued in the name of Beijing/Beiping branches for any banks. |

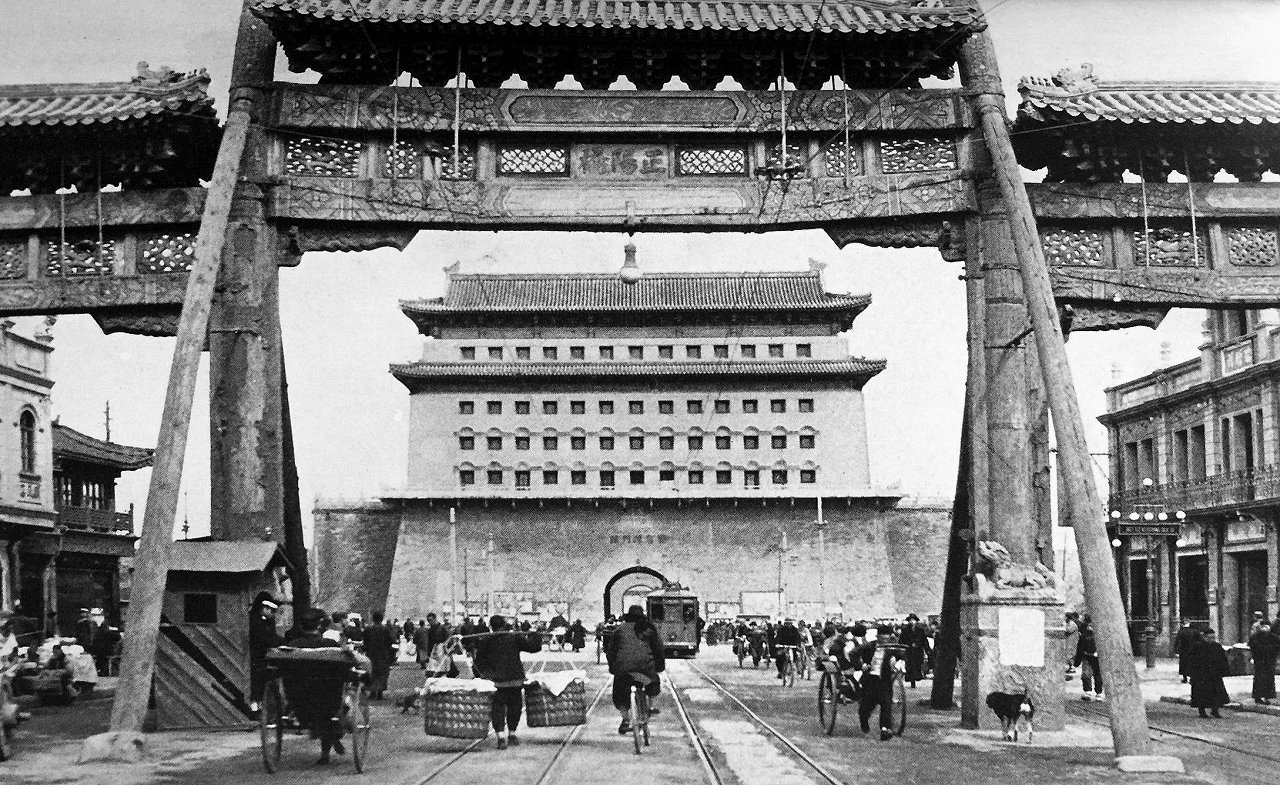

Above: the Zhengyangmen Gate, c1920s, often known as Qianmen, in the now mostly demolished city wall. The gate survives.

Above: The Grand Hotel des Wagons Lits (right) and the Yokohama Specie Bank (left), Peking, date unknown but probably 1920-40s.

|

|

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Peking -

财政部印刷局 / 北京印刷局 "In the early 1900s, the Qing government decided to print its currency and postage stamps in China. Dr. Chen Jintao, the Yale-educated vice president of the Board of Finance, recommended building a security printing plant on the American model, using U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing methods to thwart counterfeiters. Chen hired Washington architects Milburn, Heister & Company to design the eleven-building plant in Beijing. The cost, over $5 million, included shipping expenses for U.S. construction supplies, |

machinery, and equipment. The Chinese Bureau of Engraving and Printing first printed currency at the complex in 1913 and still does so today."

Despite being a major currency printer for the government, the provinces, and commercial banks under the Qing, the Republic - and for the occupying Japanese - most currency and stamp production was still undertaken by overseas companies until the late 1940s.

The Qing government also hired two American engravers; Lorenzo J. Hatch and William A. Grant (formerly of the American Banknote Company) who moved to Beijing with their families in 1908. Working through plague and revolution, they started the bureau and trained Chinese staff, designing late Qing currency and the early Republic of China stamps and currency.

The facilities of the former Chinese Bureau of Engraving and Printing has since been absorbed into the China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation.

Source: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Some examples of BEP productions

Despite being a major currency printer for the government, the provinces, and commercial banks under the Qing, the Republic - and for the occupying Japanese - most currency and stamp production was still undertaken by overseas companies until the late 1940s.

The Qing government also hired two American engravers; Lorenzo J. Hatch and William A. Grant (formerly of the American Banknote Company) who moved to Beijing with their families in 1908. Working through plague and revolution, they started the bureau and trained Chinese staff, designing late Qing currency and the early Republic of China stamps and currency.

The facilities of the former Chinese Bureau of Engraving and Printing has since been absorbed into the China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation.

Source: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Some examples of BEP productions

|

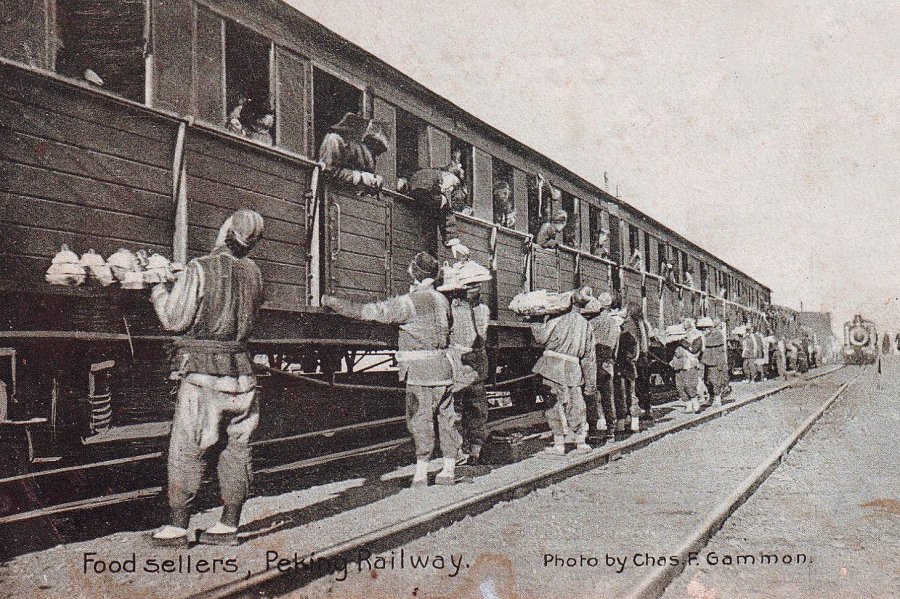

Arriving at Peking (Peter Quennell, late 1920s)

"Now and then we drew up at a wayside station and hawkers swarmed with their baskets along the carriages, growing vociferous as the train began to move. They would keep step with us for a frantic hundred yards, faces distorted, feet pounding over the platform, then drop behind and lapse into an utter passivity only less remarkable than their frenzied efforts to earn a cent or two.... " (Right: a period postcard showing this very scene on the Peking Railway) "The plain, still the plain, and some thin coppices; but we realised that we must be getting near the city. I thought of the northern approach to Rome; for this landscape somehow suggested the Roman countryside, scraps of ruin cropping out from the pale earth which had a peculier exhausted ashy glimmer.... On the left, a low crenellated wall unfolded its grey ribbon across the fields. We approached and ran through under an arch, thus entering the outer city of Peking. Here was Peking.... But what had become of its centre, its streets and houses? We were still, as far as I could see, in the open country; and that blue umbrella, half unfurled among the woods - pointed out to us from the carriage window as the Temple of Heaven - passed accidental and without meaning in the middle distance. Splinters of masonry, old tombs and broken gateways, appeared like edges of bone through the naked earth, and on the pale threadbare surface of the fields, grooved with dry watercourses and deep wheeled tracks, dark evergreens made blots of inky shadow. |

Above: Peking - the outer city, moat and walls c1900

|

Quite suddenly, then, the inner city came into view. We were looking down a long rutted lane, with carts, moving people and little houses, towards a two-storeyed gate-tower on the ramparts, its winged roof glistening faintly in the city. The inner walls were much higher than the outer circuit; they marched, grey and purposeful, to left and right, shops and houses squatted flimsily beneath them. The train swung round through a wide curve and, as the two-storeyed gate-tower fell back, we saw a blockhouse in the angle of the wall, which resembled some gigantic military dovecote, its slanting sides chequered with black squares."

(A Superficial Journey Through Tokyo and Peking, Peter Quennell, p167-168. 1932 (1986)).

Below: a busy Peking street in winter, c1946. Dmitri Kessel.

(A Superficial Journey Through Tokyo and Peking, Peter Quennell, p167-168. 1932 (1986)).

Below: a busy Peking street in winter, c1946. Dmitri Kessel.

|

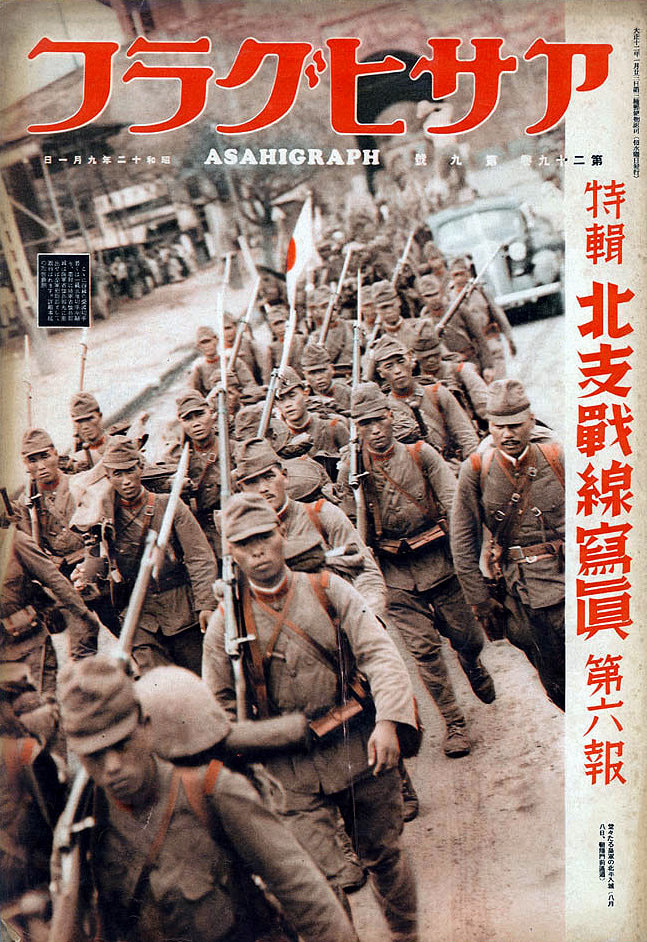

The Japanese Occupation

On July 7, 1937, the Chinese 29th Route Army, and the Japanese army in China exchanged fire at the Marco Polo Bridge near the Wanping Fortress southwest of the city. Now referred to as the Marco Polo (Lugou) Bridge Incident, this officially triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War, (World War II) as it is known in China, though in reality it was already underway. Peiping (Beijing) fell to Japan on 29 July 1937 and was made the seat of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, a puppet state that ruled the ethnic-Chinese portions of Japanese-occupied northern China. This government was merely the bureaucratic arm of the Japanese military and did not even seek formal recognition from Japan, let alone any other nation. The Shanghai banker and former Nationalist Minister of Finance Wang Kemin inaugurated and served as chairman of the puppet government until 1940 when it was officially merged into the larger Wang Jingwei government based in Nanking (Nanjing). However it was still functioning virtually independently until the end of the war. The occupation of the city was reportedly less brutal than experienced elsewhere. Considerable damage was done to important institutions including Peking University, which had been abandoned shortly after the occupation (the PKU, Tsinghua University and Nankai University were relocated southward to Hunan Province, where they became one university called the National Provisional University at Changsha). |

The Federal (or United) Reserve Bank of China was created to serve this Northern puppet regime; formed out of the merging of several short lived predecessors.

The Provisional Government declared that the Chinese national currency issued by the Koumintang (Guomindang) government could only remain in circulation for one year before its own Federal Reserve Bank notes would become the only accepted currency of the region. Initially helpful to the new regime, it was not long however before mass inflation began. Additionally neither Chinese merchants nor Japanese businessmen decided to accept the new bank notes, and laws were eventually passed prohibiting refusal. The Kuomintang currency remained in use everywhere outside of the Japanese military's immediate reach, while Communist guerrillas operating in north China declared it illegal to possess Federal Reserve Bank notes. Those who did so were threatened with execution.

The bank continued after the merging of the puppet governments, until it's abolition in 1945 following the defeat of Japan.

The Provisional Government declared that the Chinese national currency issued by the Koumintang (Guomindang) government could only remain in circulation for one year before its own Federal Reserve Bank notes would become the only accepted currency of the region. Initially helpful to the new regime, it was not long however before mass inflation began. Additionally neither Chinese merchants nor Japanese businessmen decided to accept the new bank notes, and laws were eventually passed prohibiting refusal. The Kuomintang currency remained in use everywhere outside of the Japanese military's immediate reach, while Communist guerrillas operating in north China declared it illegal to possess Federal Reserve Bank notes. Those who did so were threatened with execution.

The bank continued after the merging of the puppet governments, until it's abolition in 1945 following the defeat of Japan.

|

Above: December 1938; the Japanese army’s new commander of the North China Area Army, Hajime Sugiyama, visited Wang Kemin (seated left), chairman of the administrative committee of the Puppet North China Provisional Government.

|

Above: a series of 1918 1 Yuan of the Bank of China, Shanghai branch, issued during 1922-1923 when Wang Kemin was Governor for a second time. His signature appears very distinctly on the left.

|

|

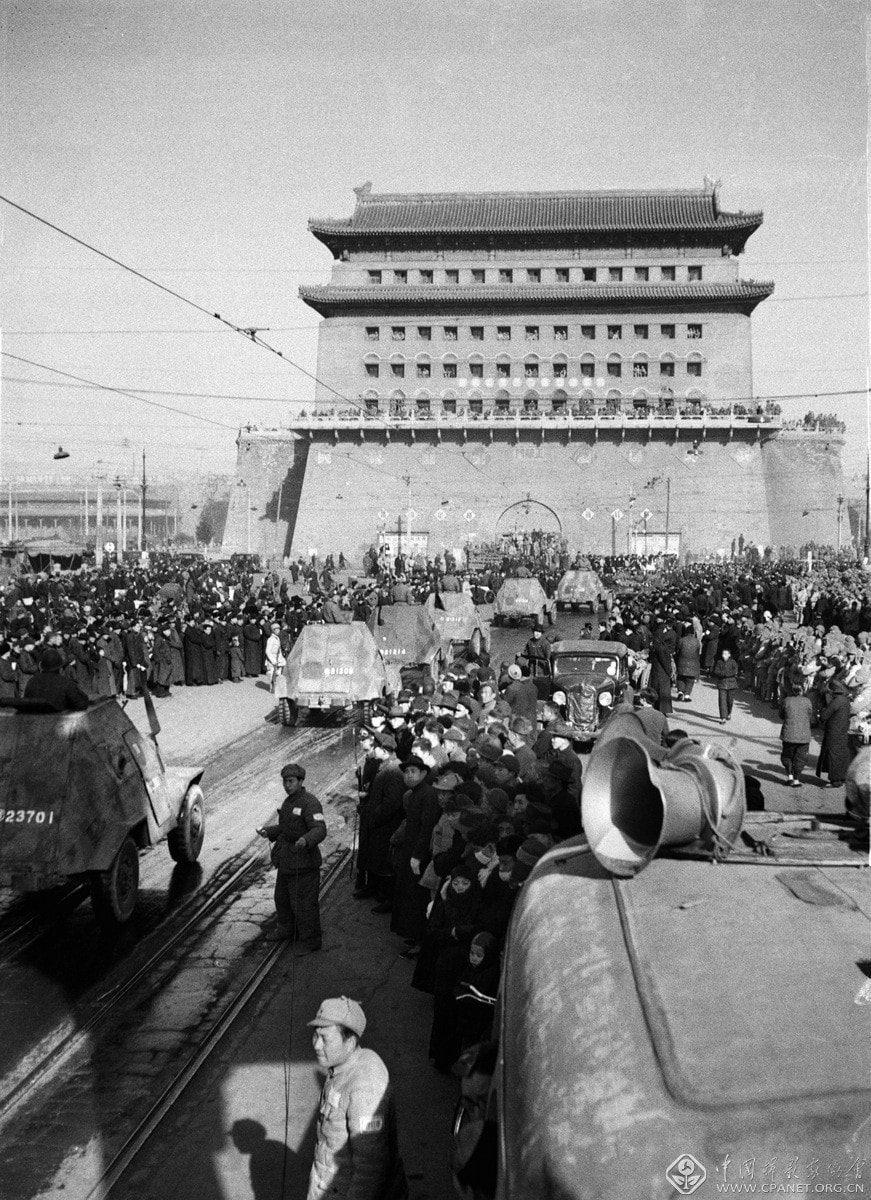

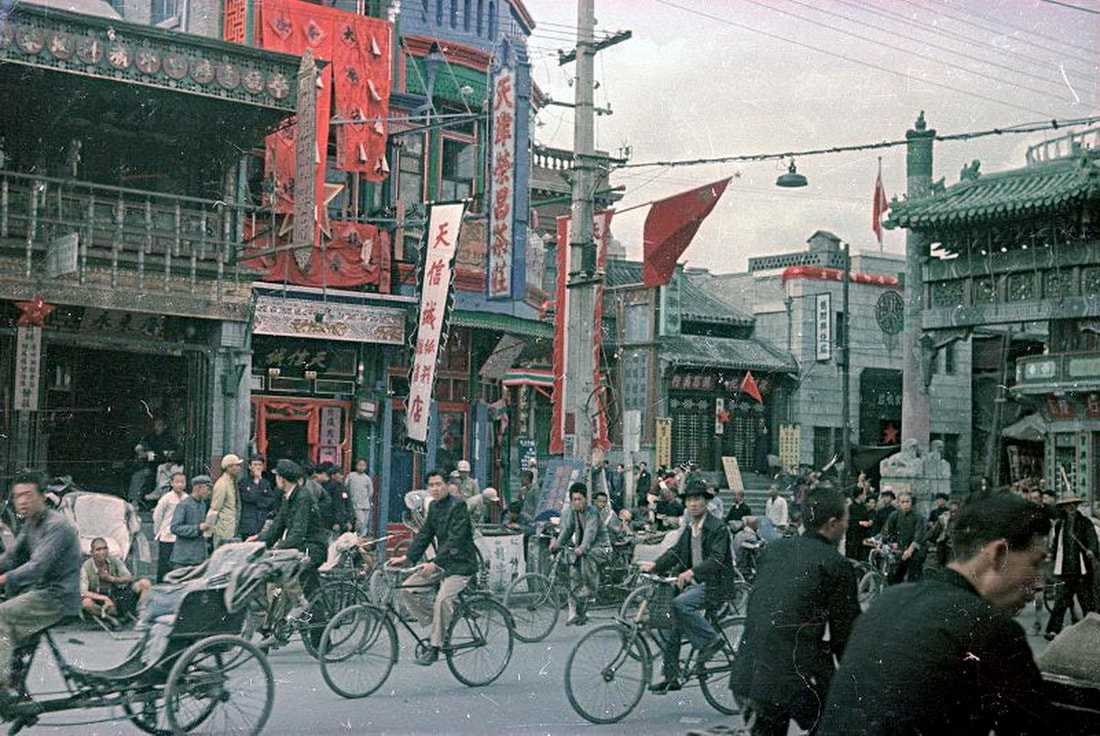

The return of the Nationalists, rise of the Communists

Following the end of WWII, the shaky alliance between the Nationalists and Communists soon fell apart; American led efforts to prevent the resumption of the 1927-1937 Civil War failed, and the beginning of the second and final phase of the war broke out in July 1946. During 1948 the Communists began to gain the upper hand, capturing strategic regions in the North and defeating the KMT's 'best' army at Changchun. The People's Liberation Army seized control of the city itself peacefully on 31 January 1949 in the course of the Pingjin Campaign. On 1 October that year, Mao Zedong announced the creation of the People's Republic of China from the platform of Tian'anmen. He restored the name and status of the city, as the new capital, to Beijing. In the 1950s, the city began to expand beyond the old walled city and its surrounding neighborhoods, with heavy industries in the west and residential neighborhoods in the north. The Nationalists had cleared some of it previously, but most of the ancient Beijing city wall was sadly torn down in the late 1950s to make way for the construction of the Beijing Subway and the 2nd Ring Road. Right: Communist forces enter Beijing, February 1949. Below: a busy street in the new capital, c1949-1950 - photo by Vladislav Mikosha |