Updated 20 January 2018

Tientsin - Tianjin - 天津 |

|

Tientsin (now written as Tianjin) is the port city for nearby Peking (Beijing), and was once within Chihli (Zhili) province, later Hopei Province (Hebei). The name means "The Ferry Site of the Emperor", or "Emperor's Ford", a name used since 1404 when the settlement (previously named Zhigu) was reconstructed as a walled city, with a large military base.

The area had been an important centre of trade from the construction of the Grand Canal during the Sui Dynasty (581-618), with the first significant settlement built during the Song dynasty (960-1126). The city rapidly developed as the main gateway to Peking (Beijing). |

Following the end of the Second Opium War (1860), Tientsin became a Treaty Port, opening to foreign trade and the establishment of foreign controlled self-contained concessions of which there were at one point nine. The most significant were those of Britain, France and Japan.

Anti-foreigner tensions simmered and finally erupted, including such as the 'Tianjin Church Incident' of 1870. Roman Catholic missionaries who ran an orphanage attached to the then newly built Wanghailou Church (Church Our Lady's Victories) were accused of the kidnap and brainwashing of Chinese children. Tensions escalated into a riot in which both the church and nearby French Consulate were burnt and 18 people killed including 10 nuns and the Consul. The Qing government was forced to pay compensation for the attacks. 30 years later the concessions were attacked again during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. These renewed antiforeign demonstrations led to the shelling and occupation of the city by Allied (Western) forces and the destruction of the old city wall.

The Qing general, minister and Viceroy of Zhili province; Yuan Shikai, began to modernise the city from 1902, establishing a modern police force of 2000 men, and a democratically elected city council. (photo: Tientsin police in 1912).

In the lead up to the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, Tientsin was a regional centre for anti-monarchist activity: "Some influential revolutionary activities, such as the Beijing Uprising, were plotted in Tianjin," ... "After the 'Preparatory Council for Constitutionalism' in 1906, Tianjin became the center of the United League of China, a nationwide revolutionary society."

Tianjin historian Zhang Shaozu.

Below: (left) The Drum Tower, covered with advertising including the trademark of 'General Jintan' (the hat wearing bust) of Morishita Ren Dan - China - First Aid drug. Morishita (a Japanese company) still exists. (right) The Japanese Concession.

A Steamer to Tientsin (Peter Quennell, late 1920s):

"The day was over when we reached the suburbs of Tientsin, and a factory whistle blew dismally from a yard. There was some shouting when a child fell into the river and was fished up, breathless and dripping, among the boats. Through the cold grim twilight which was closing down, we saw the dark water-front of the modern city; villas, banks and warehouses in dark brick, a crowded quayside and a line of anchored vessels.

The steamer edged in towards the quay, and amid the Chinese crowd, densely packed beneath the rail, I noticed two Europeans standing apart. 'White Russians, probably,' said my companion, both unspeakably haggard and the worse for wear, in dirty hats, frayed collars and shapeless overcoats, gazing with pinched faces at the deck, waiting, perhaps, for someone who never arrived....

Upturned faces, shaven heads beneath the rail; then the gang-plank was dragged noisily into place. The entire crowd seemed to shove forward across the gangway, and were in a moment swarming and trampling through the ship - money changers clinking silver-dollars, vague officials, soldiers and a rabble of coolies. They elbowed us; they argued fiercely over our luggage. It was snatched up and trundled off into the darkness.

The hotel entrance was a few steps across the quay. A door closed on twilight and confusion, and the smell of floor polish and a wealth of scarlet and gold paint emphasised the nationality of the proprieter. He was English; that went without saying; it was all so clean and tasteless and good-natured. ...English residents passed stiffly to and fro. A middle-aged woman with a lapdog under her arm, waddled with flaccid dignity through the lounge. Two young officers, Sandhurst to the backbone, sat irreproachable and aloof in a far corner; while the Chinese boys, like queer archangels in their white robes, slipped sulky looking but attentive between the chairs.

Newspapers were hanging in a rack; and from these we learned that a pair of female missionaries had just been murdered in a city of the interior and that such-and-such a bandit was on the move; tens of thousands reported dead from another place - announcements which occupied as little room as a flower show in some local English sheet. Instead of a Harvest Festival there was a massacre, a rumoured insurrection instead of a christening. The journalists had taken their cue from the landscape; they had forgotten to appear ever so slightly surprised...."

(Source: 'A Superficial Journey Through Tokyo and Peking' - Peter Quennell. p164-166)

Gordon Hall and the Concessions

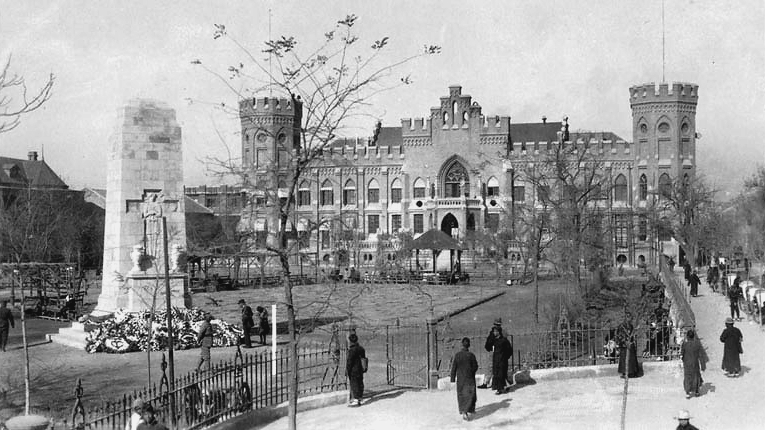

Gordon Hall was the administrative centre of the British Concession; an eccentric gothic building that would have looked out of place in China if not for being surrounded by streets of equally alien architecture - though this was one of the more unusual examples. In front stood a typically British municipal park which could have been transported from any town in Britain, and complete with a WWI war memorial. The Concession was formally handed back to the Nationalist Government, then based at Chungking, in 1943, though they were unable to take possession for another two years until the defeat of the Japanese who then occupied Tientsin and much of eastern and northern China. The Hall (below, left) managed to survive the war, and the Cultural Revolution fairly unscathed but was severely damaged in an earthquake in 1984. A restored remnant of what appears to be one side of the building remains (below, right).

Gordon Hall was the administrative centre of the British Concession; an eccentric gothic building that would have looked out of place in China if not for being surrounded by streets of equally alien architecture - though this was one of the more unusual examples. In front stood a typically British municipal park which could have been transported from any town in Britain, and complete with a WWI war memorial. The Concession was formally handed back to the Nationalist Government, then based at Chungking, in 1943, though they were unable to take possession for another two years until the defeat of the Japanese who then occupied Tientsin and much of eastern and northern China. The Hall (below, left) managed to survive the war, and the Cultural Revolution fairly unscathed but was severely damaged in an earthquake in 1984. A restored remnant of what appears to be one side of the building remains (below, right).

|

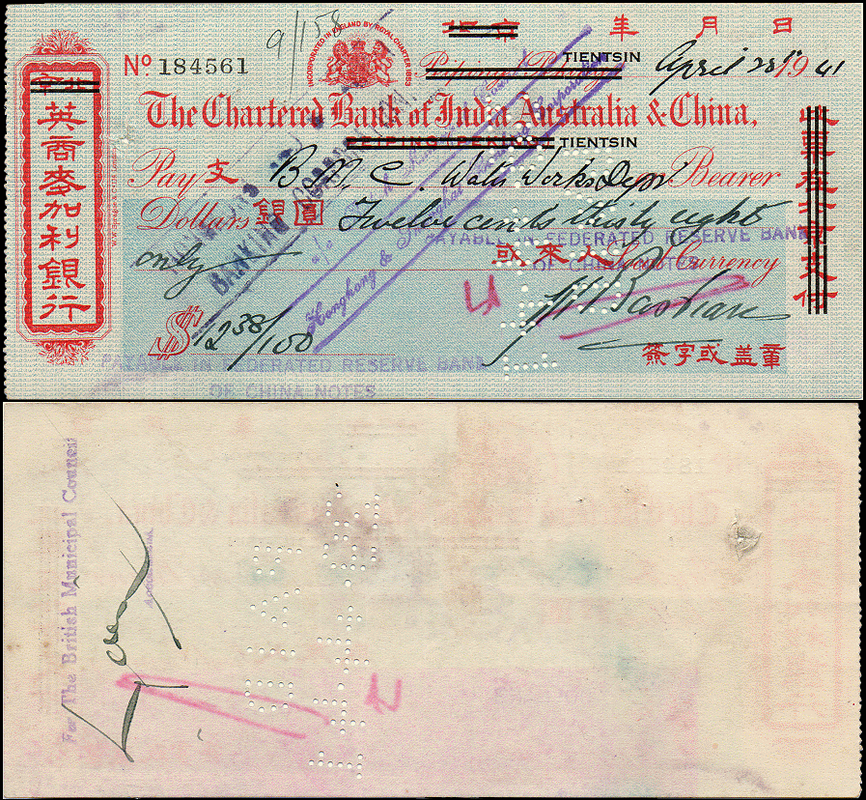

Right: A cheque for $0.12.38 payable to the British Municipal Council - Waterworks Department. Issued in April 1941 during the Japanese occupation of 'Chinese' Tientsin, but before their occupation of the Concessions, in December 1941 . Marked as payable in ‘Federated Reserve Bank of China notes’ and crossed by the HSBC. The council was based in Gordon Hall. |

Beginning with the British and French Concessions established from 1860, there were 9 concessions in total. The US concession was only informally held and became part of the British Concession in 1902. The Austrian, German and Russian Concessions ceased early; between 1917-1920, due to WWI and the Russian Revolution. Belgium gave up it's concession in 1931. The remainder were steadily handed back to Chinese control from 1943, with the Italian concession the last to cease, in 1947.

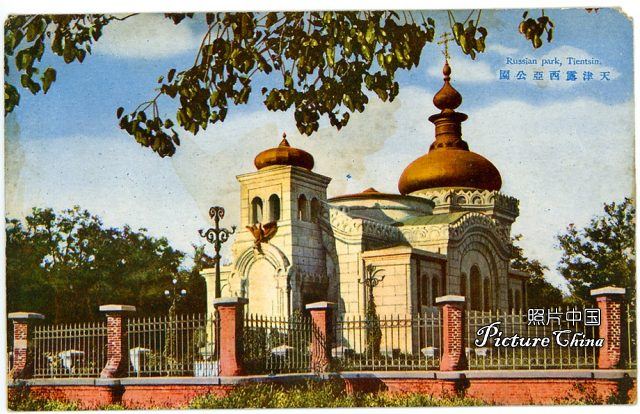

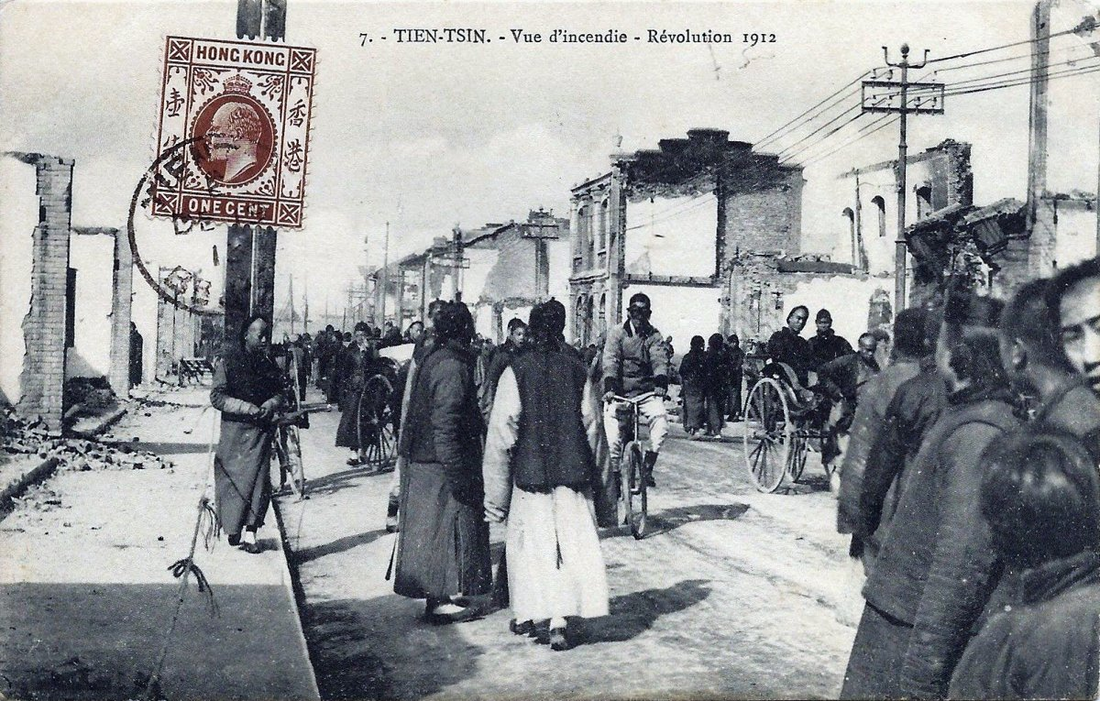

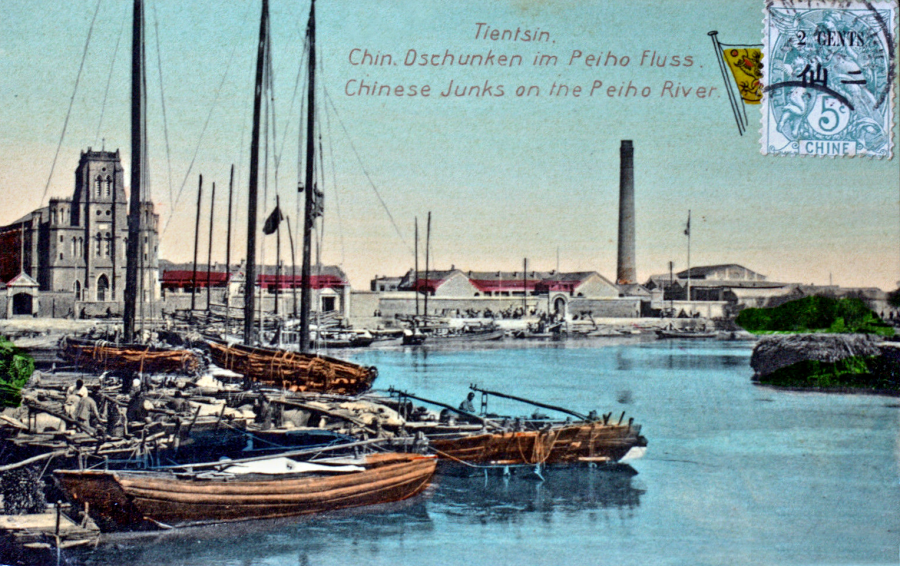

Below: (top left) A Russian Orthodox church in the Russian Park. (top right) numerous destroyed and fire damaged buildings, casualties of the 1912 revolution. (lower left) junks on the Peiho River which runs through Tientsin, with the French Catholic former cathedral, the Wanghailou Church, and factories in the background. (lower right) a crossroads in the French Concession.

Below: (top left) A Russian Orthodox church in the Russian Park. (top right) numerous destroyed and fire damaged buildings, casualties of the 1912 revolution. (lower left) junks on the Peiho River which runs through Tientsin, with the French Catholic former cathedral, the Wanghailou Church, and factories in the background. (lower right) a crossroads in the French Concession.

The Last Emperor

In early 1925 Aisin Gioro Puyi, the last emperor of China who had abdicated as a child in 1912, was evicted from the Forbidden City in Peking (Beijing) by the Warlord General Feng Yuxiang (founder of the Bank of the Northwest). The Imperial Court had been essentially confined there since the revolution of 1912, in a deal with the new republican government in which Pu Yi and his court retained their titles and control of the central part of the Forbidden City, and the nearby Summer Palace. However in November 1924 following a successful coup against the government by Feng Yuxiang, the agreement with Puyi and the Imperial Court was annulled: the emperor was stripped of his now honorary titles and expelled from the palace.

Puyi and his core entourage briefly moved to his father's house in Peking, however, fearing for his safety he moved to the Japanese Concession in Tientsin in February 1925, and firmly into the influence of the Japanese. He first lived at the Zhang Garden residence, and then moved to a large villa, the Garden of Serenity in 1927. While there, he and his advisors debated plans to one day restore his rule, and negotiations were entered into with the Japanese with the aim of achieving this. During 1931, Manchuria was seized by Japan. Puyi left Tientsin in November for Manchuria where plans were finalised to install Puyi as the Chief Executive for the new Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuria, NE China - the homeland of the Manchu Qing Dynasty). In 1934 he was officially crowned as the Kang-de Emperor, and remained as the puppet ruler of Manchukuo until Japan's surrender in August 1945.

In early 1925 Aisin Gioro Puyi, the last emperor of China who had abdicated as a child in 1912, was evicted from the Forbidden City in Peking (Beijing) by the Warlord General Feng Yuxiang (founder of the Bank of the Northwest). The Imperial Court had been essentially confined there since the revolution of 1912, in a deal with the new republican government in which Pu Yi and his court retained their titles and control of the central part of the Forbidden City, and the nearby Summer Palace. However in November 1924 following a successful coup against the government by Feng Yuxiang, the agreement with Puyi and the Imperial Court was annulled: the emperor was stripped of his now honorary titles and expelled from the palace.

Puyi and his core entourage briefly moved to his father's house in Peking, however, fearing for his safety he moved to the Japanese Concession in Tientsin in February 1925, and firmly into the influence of the Japanese. He first lived at the Zhang Garden residence, and then moved to a large villa, the Garden of Serenity in 1927. While there, he and his advisors debated plans to one day restore his rule, and negotiations were entered into with the Japanese with the aim of achieving this. During 1931, Manchuria was seized by Japan. Puyi left Tientsin in November for Manchuria where plans were finalised to install Puyi as the Chief Executive for the new Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuria, NE China - the homeland of the Manchu Qing Dynasty). In 1934 he was officially crowned as the Kang-de Emperor, and remained as the puppet ruler of Manchukuo until Japan's surrender in August 1945.

Below, left: Puyi, 2nd from left, with his tutor Reginald Fleming Johnston (left) and the 'empress' at right, seated in the grounds of the Zhang Garden in 1926. Below right: Puyi in Tientsin, or shortly after his arrival in Manchukuo.

The End of Western Colonialism, and the Rise of Japan

|

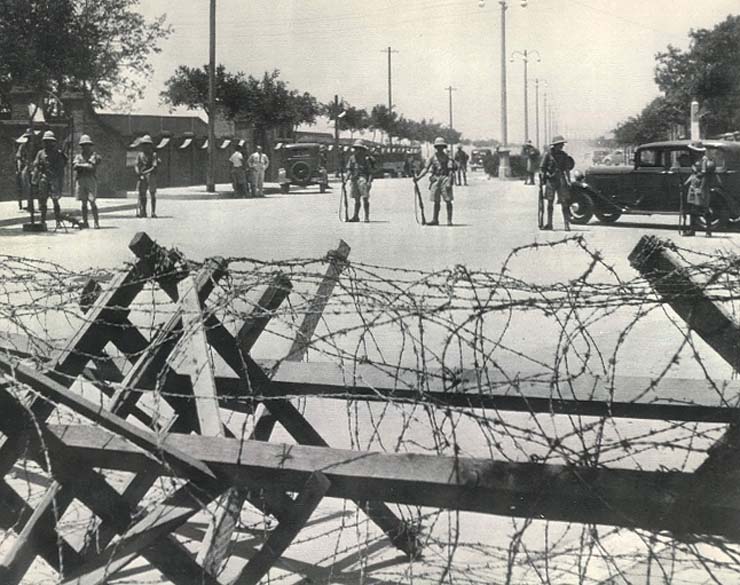

The border between the British Concession and Japanese occupied Tientsin in 1939.

|

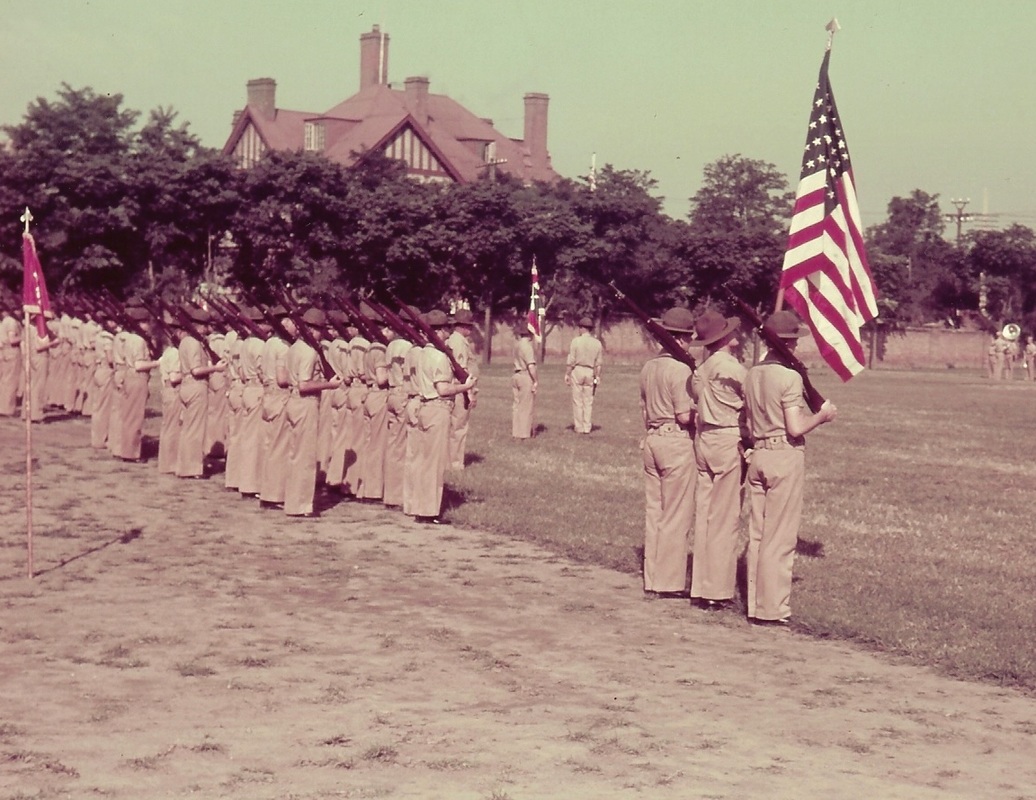

Rare pre-WWII colour image of the US Tientsin Marines drilling on their parade field. source: chinamarine.org/Tientsin.aspx

|

|

On July 30, 1937, Tianjin fell to Japan, as part of the Second Sino-Japanese War, but was not entirely occupied, as the Japanese for the most part respected foreign concessions until December 1941, when the American and British concessions were occupied following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war between Japan and the western Allies.

The British troops stationed there had already left by 1940, as had many British residents. The remaining US unit was less fortunate and surrendered on December 8th. The French (Vichy) and Italian Concessions were allowed to remain under their own governance due to their position as a client state (France) and a member state (Italy) of the Axis. In September 1943 however, the Japanese invaded and took control of the Italian Concession when Italy signed an armistice with the Allies. The occupation ended on August 15 1945 with the defeat and surrender of Japan. Right: A Federal Reserve Bank of China 500 Yuan of 1943. One of numerous issues by this Japanese puppet bank which would have circulated in Tientsin until August 1945. The note depicts the main hall of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, and Confucius. |

Short newsreels of the early period of Japanese Occupation:

|

|

|

|

From Civil War, and the 1949 Revolution, to the present

In the Pingjin Campaign of the Chinese Civil War, the city was captured after 29 hours of fighting. Finally the Communists took over Tianjin on 15 January 1949. The city suffered to some degree during the cultural revolution of the 1960s, though a significant amount of Tianjin's heritage survived mostly unscathed - albeit mostly European and Japanese colonial in origin. Today, Tianjin is the third largest municipality in China, with a population of 13 million people. It is the leading port and centre of manufacturing in North China. Right: The aftermath of a Cultural Revolution rally at the French Catholic cathedral in 1967. |

Tientsin Bank Branches, Banknotes and their Vignettes

|

The Bank of China 中國銀行

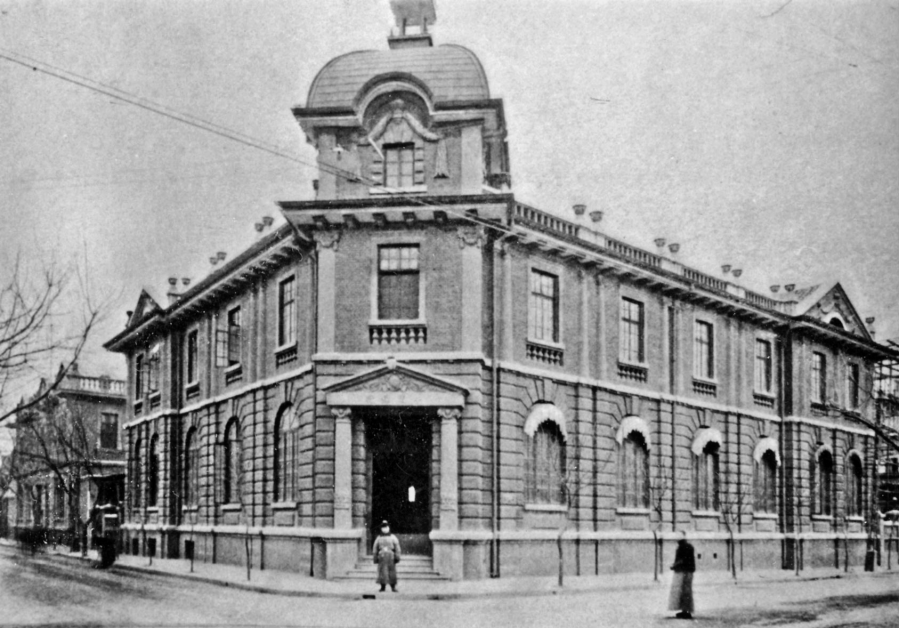

Above: the main branch of the Bank of China in Tientsin which during the course of the 1920s the Peking branch became subordinate to, with the banks headquarters moving from Peking to Shanghai in 1927. All of the Peking branch's capital was transferred to Tientsin in 1932. Right: A 5 Yuan of 1931 issued by and depicting the Tientsin branch. Printed by De La Rue. SCWPM 70b (issued c1935). |

The Bank of Communications 交通銀行

|

In 1925-27 part of the headquarters of the Bank was relocated from Peking to Tientsin (Tianjin) due to Peking's shift towards industry and away from politics. Indeed within a year the seat of government would be moved to Nanking (Nanjing), and Peking was in addition soon not felt to be a commercial centre either. Warlordism and other political strife before the removal of the capital to Nanjing in 1928, had compromised the Peking branches of the major banks. Few if any banknotes were issued by the Peking branch in it's own name after 1917, and the Tientsin branch became dominant in the region. Tientsin branch notes stamped with an 'H' are known to have been redeemable only at the Peking branch, and were assumedly issued by such. The principle headquarters moved to Shanghai in 1928.

Upper right: a 5 Yuan of '1914' printed in the less usual red. The bulk of the 5 Yuan across the Bank of Communications branches was printed in dark charcoal-brown from the mid 1920s onwards. The exceptions include a rare Sian (Xian) branch issue in orange-yellow, and these red issues of the Tientsin branch, found in two main types. This is the latter type with the national (Shanghai) branch signatures, issued from 1933. The colour change was apparently in response to a wave of forgery in the late 1920s. One of two versions cataloged as SCWPM 117s ( Smith & Matravers C126-96a). Right: a scarce and little known specimen of a mostly unissued series planned for 1931. This was for the Tientsin branch. This design was later reused for the purple 1 Yuan of 1935. A Tientsin and a Shanghai 5 Yuan was also planned but never issued. Only the red 1 Yuan of the Shanghai branch appeared (SCWPM P 148). Below: The old Tientsin branch located in the French Concession. |

Pei Yang Tientsin Bank 北洋天津銀號

|

Established in c.1902, very little is known about this Tientsin based bank. It seems to have been semi-official and was merged into the Provincial Bank of Chihli in 1910. It is well known for a series of very rare and highly attractive banknotes printed by Bradbury & Wilkinson, depicting the Qing politician Li Hung Chang (Li Hongzhang). Cheap fakes of these notes are frequently encountered on the internet, some selling for $50 USD or more. Right: 3 Taels of 1910 |

The Provincial Bank of Chihli (Zhili) - 直隷省銀行

|

Established in 1910 out of the Peiyang Tientsin Bank. Closed in 1928. Re-organised as the Bank of Hopei (Hebei) in 1929 following the change of the province name.

The bank was forever in trouble during the 1920s, needing to be bailed out by loans and subject to numerous 'runs on the bank' partly caused by the irresponsible behaviour of bank officials. The provincial government's vast appetite for resources led to the issuance of vast amounts of money through the bank to help pay for such, an increase that was not supported by a comparable increase in silver reserves, which inevitably led to trouble. Even executions for speculation, and other extreme measures failed and the crisis grew ever worse with the provincial notes being illegally discounted by over 30% of their face value, and often being refused altogether. In the late 1920s, the Peking-Mukden and Tientsin-Pukow Railways were forced to accept notes of this bank in payment of freight and passenger fares as evidenced by the “BAGGAGE” and oval station-master (in Chinese characters) chops found on the reverse of some notes. Right: 1 Yuan of October 1st 1926, Tientsin branch. The front depicts the 'First Pass under Heaven' (Zhendong Gate Tower) -the Shanhaiguan Pass on the Great Wall. |

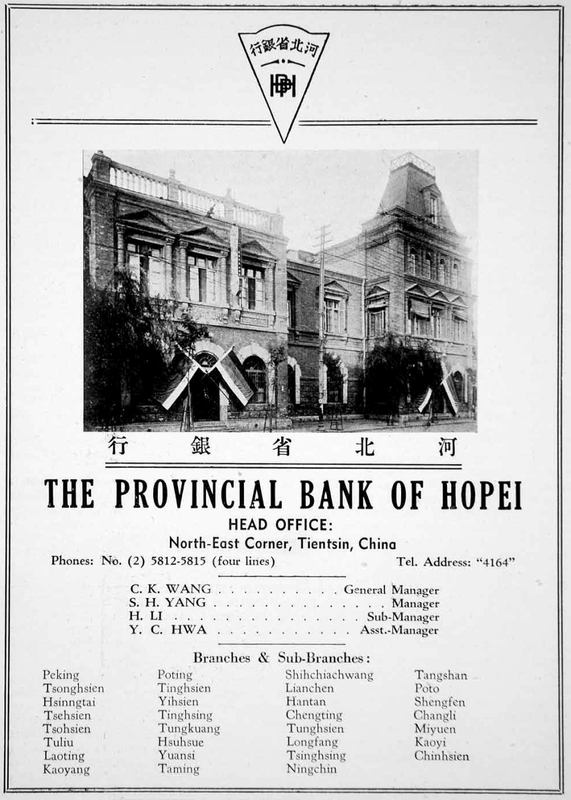

(Provincial) Bank of Hopei - 河北(省)銀行

|

The head office was briefly at Peking, and then Pao-Ting (Baoding: provincial capital from 1928-58, 1966-70) but was relocated to the French Concession at Tientsin (Tianjin) from 1930 to 1938. Formerly the Provincial Bank of Chihli, the bank was re-organised in 1929. The notes are known to have been widely used on the trains of the Cheng-Tai (Shihchiachwang-Taiyuan) Railways, during the 1930s. By 1937 the currency issue of the bank was being described as 'out of control' partly due to pressure from the expanding Japanese occupation and influence in North China. (China's nation-building effort, 1927-1937: the financial and economic record, by Arthur Nichols Young, p272) During this period the bank became fully under the control of the Japanese who in 1938 moved the headquarters from within the French Concession at Tientsin, and into fully Japanese controlled territory. The bank had previously been bombed by the Japanese in 1937. The situation was this: "When the Japanese overran Peiping (Beijing) they captured the dies from which these bank notes were printed. They immediately began to turn them out in great numbers and pump them into the Liberated Areas to buy up produce." The authorities of the communist Central Hopei base undertook counter-measures immediately, announcing that a new currency would be introduced and that after a certain date only this currency would circulate. They split the region into zones, naturally giving a better exchange rate for the withdrawn provincial notes in the areas furthest away from Japanese occupation. (The Unfinished Revolution in China, by Israel Epstein, 1947, p291) From the Western Mail (Perth, Australia) May 28 1936: LONDON, May 26.-Japan has taken the first overstep towards creating an in- dependent currency for North China by making the Bank of Hopei the sole bank of issue in the provinces of Hopei and Chahar. It is believed that the Chinese central Government's notes will be ousted, paving the way for the yen and linking North China with Manchukuo. The Japanese ban on non-Federal Reserve Bank notes was placed on and after March 11 on all the old currency notes that had circulated in North China, including those issued by the Provincial Bank of Hopei. The issues of this bank however were allowed to circulate for a further two months. (Kyoto University Economic Review, MONETARY AND FINANCIAL REORGANIZATION IN NORTH CHINA, Apr-1940, p77-80) Right: a 1930s flyer or poster advertising the bank, with a rare photo of the Tientsin head office, and a list of senior staff and branch offices. |

Above: The 2 Yuan of 1934 - but most likely issued after 1937 due to the signature changes from lower denomination notes of the same given date. This note is found with two overprint types: numerical (as above), or with Chinese characters.

The signatures are of (left): 楊天受 (Yang Tianshou), written as "Tian Shou Yang" and (right): 姬奠川 (Ji Dianchuan), written as "T.C.Chi". The front depicts the White Dagoba (pagoda) also known as the Bai Ta Stupa, in Beihai Park, Peking. SCWPM S1730b. |

Tah Chung Bank - 大中銀行

|

Apparently established in March 1919 by Wang Yunsong as General Manager and Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yatsen), with branches at Chengdu, Wuhan, Shanghai, Tianjin, Beijing, and Qingdao. The banks headquarters seems to have been initially at Tientsin (Tianjin) but later relocated to Shanghai. Right: a Tientsin branch 10 cents National Currency issue of 1932. |

The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China - 印度新金山中國麥加利銀行

|

A British bank founded at Karachi, India (now in Pakistan), in 1853. The name is derived from the royal charter obtained from Queen Victoria to establish the bank. The bank merged in 1969 to become the Standard Chartered Bank, which is still one of the three currency issuing banks for Hong Kong. The Tientsin agency of the bank was opened in 1895, with the support of the Qing Statesman Li Hongzhang. Large quantities of tea came through Tientsin for export over-land to Russia, as well as substantial imports of salt and rice, trade the bank intended to 'tap in to'. Initially, funds for the agency were largely derived from the sale of Shanghai taels to the local Chinese banks. In 1939, major flooding in Tientsin completely submerged the basement, rendering the vault innaccessible for over a month. Right: A scarce Tientsin branch 10 dollars issue of 1930, printed by Waterlow & Sons, London. |

The Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) 香港上海匯豐銀行

|

The HSBC was the largest and most important of the foreign banks in China, established in Hong Kong in 1865 to finance trade between China and Europe, issuing currency within the treaty ports, most significantly Shanghai. It was, and remains the principal bank and note issuer in Hong Kong. The Tientsin branch of issue was rebuilt in 1925, located on what was then Victoria Road in the British Concession. Unlike the Shanghai branch, most of the clients seem to have been Chinese. At the end of the 19th century, one of the Tientsin branches more notable clients was the renowned Qing Court official Li Hongzhang who deposited at least 1.5 million taels. Right: HSBC 5 Dollars (local currency) Tientsin Branch issue of 1920. Printed by Waterlow & Sons Ltd. The back depicts the old Hong Kong HSBC headquarters building. |