The Temple of Heaven - 天坛 Tiāntán - Beijing

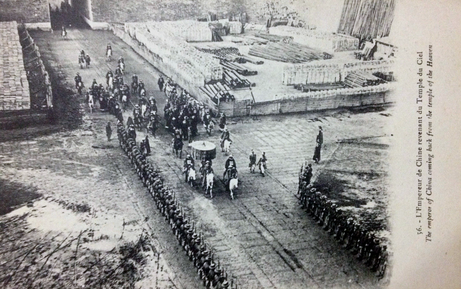

The Guangxu Emperor (d.1908) returning from the Temple of Heaven.

The Guangxu Emperor (d.1908) returning from the Temple of Heaven.

The Temple of Heaven, founded in 1420, is a superb complex of 660 acres of fine cult buildings set in gardens and surrounded by historic pine woods. In its overall layout and that of its individual buildings, it symbolizes the relationship between earth and heaven – the human world and the heavenly realm – which stands at the heart of Chinese cosmogony, and also the special role played by the emperors within that relationship. The temple is the largest and most complete of it's type in China and the wider world. Though regarded as a Daoist temple, Heaven worship is the oldest surviving religious tradition in China, predating Daoism and can be traced back at least three to four thousand years, to the Xia Dynasty.

The significance and longstanding popularity of the monument has made it a natural choice as a symbol of China from the declining decades of the Qing Dynasty through to the Republic and at various periods to the present. As such it has been frequently depicted on the currency and stamps of China, both official national issues and numerous regional issues - including the Japanese puppet notes for occupied China.

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is the three-tiered circular structure which most people think of as 'the temple,' and is the feature most commonly depicted on money - and elsewhere - is only a part of the complex: in total there are 92 ancient buildings incorporating 600 rooms.

Located south of the Forbidden City on the east side of Yongnei Dajie, the original Altar of Heaven and Earth was completed together with the Forbidden City in 1420, the eighteenth year of the reign of the Ming Emperor Yongle. In the ninth year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1530) the decision was taken to offer separate sacrifices to heaven and earth, and so the Circular Mound Altar was built to the south of the main hall for sacrifices particularly to heaven. The Altar of Heaven and Earth was thereby renamed the Temple of Heaven in the thirteenth year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1534). The current arrangement of the Temple of Heaven complex was formed by 1749 after reconstruction by the Qing emperors Qianlong and Guangxu. After this the site remained little changed. The Hall itself was damaged by fire and largely rebuilt in replica the 1890s, and the complex suffered some damage during it's occupation by Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

The significance and longstanding popularity of the monument has made it a natural choice as a symbol of China from the declining decades of the Qing Dynasty through to the Republic and at various periods to the present. As such it has been frequently depicted on the currency and stamps of China, both official national issues and numerous regional issues - including the Japanese puppet notes for occupied China.

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is the three-tiered circular structure which most people think of as 'the temple,' and is the feature most commonly depicted on money - and elsewhere - is only a part of the complex: in total there are 92 ancient buildings incorporating 600 rooms.

Located south of the Forbidden City on the east side of Yongnei Dajie, the original Altar of Heaven and Earth was completed together with the Forbidden City in 1420, the eighteenth year of the reign of the Ming Emperor Yongle. In the ninth year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1530) the decision was taken to offer separate sacrifices to heaven and earth, and so the Circular Mound Altar was built to the south of the main hall for sacrifices particularly to heaven. The Altar of Heaven and Earth was thereby renamed the Temple of Heaven in the thirteenth year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1534). The current arrangement of the Temple of Heaven complex was formed by 1749 after reconstruction by the Qing emperors Qianlong and Guangxu. After this the site remained little changed. The Hall itself was damaged by fire and largely rebuilt in replica the 1890s, and the complex suffered some damage during it's occupation by Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Despite it's obvious imperial associations, the importance of the site ensured that it continued as a symbol of China after the 1911 revolution, throughout the Republic - though ceremonial sacrifices and other rituals to Heaven were banned, and the site left un-managed for some years. However, the very last imperial rite performed at the Temple occurred in late 1914. The politician and general Yuan Shi-kai conspired his way into power, becoming the first President of China after provisional president and founder of the Republic, Dr Sun Yatsen had given way in order to maintain the stability and survival of the new political order. However Yuan had other ideas and by 1914 was preparing to proclaim himself Emperor. In this goal he performed the Imperial sacrificial rites at the Temple of Heaven. When he finally did take the throne, his reign lasted a mere 83 days as unrest and civil war broke out in opposition to his new status. Expecting support from foreign powers, he was dismayed to receive none and abdicated, dying soon after. His presidential and imperial rule fatally damaged the Republic, leading to warlordism, further civil war and a nation less able to fend off Japanese Imperialism.

The Temple and grounds opened to the public in 1918.

The complex further survived the Cultural Revolution during the 1960s, though with some damage and neglect, and the loss of some edge sections of the parkland. The site re-opened during the late 1970s.

Some examples of the money

Above: Aluminium 1 Jiao of 1941, issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of China. The bank has been authorised by the puppet Provincial Government of China to issue coinage from it's outset, but in the event and for reasons unknown, the bank substituted coins for paper notes until these issues, minted from 1941 to 1943.

|

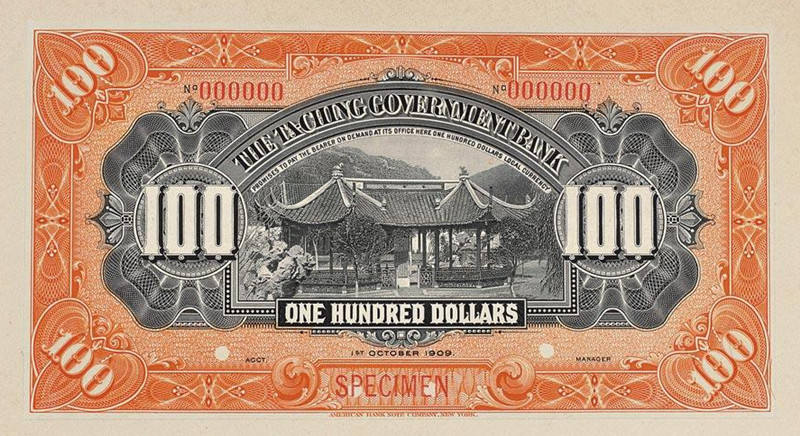

The Ta Ching Government Bank 100 Dollars of 1909. This would appear to be the first instance of both the appearance of the Temple on Chinese currency, and the first use of this specific vignette of the Hall of the temple by the American Banknote Company. These notes never entered circulation, and the bank was reformed in 1912 as the Bank of China.

|

|

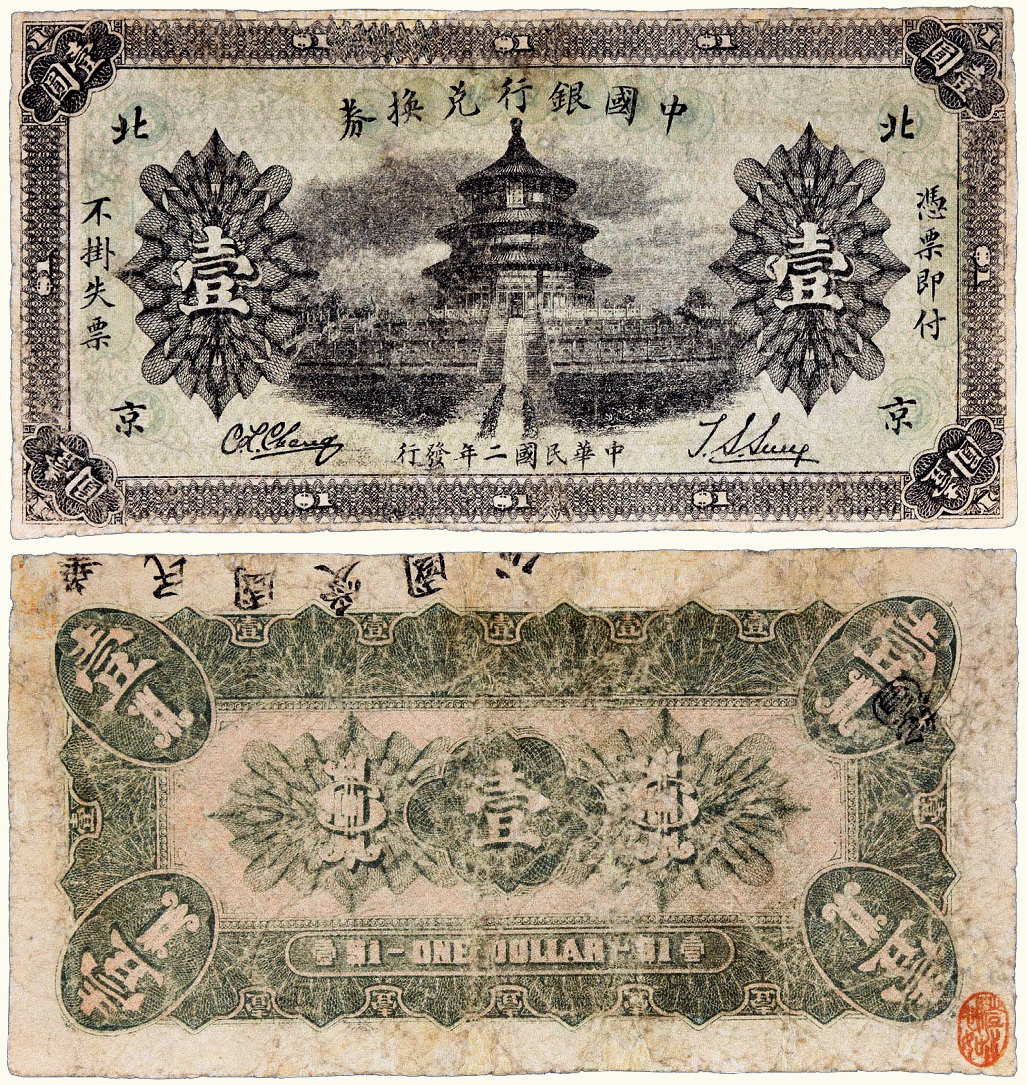

Bank of China 1 Yuan of 1918 (circulated after 1934). This note has a large number of varieties in terms of colour, branch, signatures and overprints, some of which are uncatalogued, and was placed into circulation until at least the late 1930s.

|

Bank of China 1 Dollar of 1912/13. Rare early post imperial provisional issue re-using the back design of unissued Ta Ching Government bank notes of c1909.

|

|

Bank of China 100 Dollars of 1913 (specimen). Shows an early (though not first) use of this specific vignette of the Main Hall by the American Banknote Company. This would be reused on various ABNC notes until 1943.

|

Bank of China 5 Yuan of 1931 (Tientsin Branch). A design that doesn't quite work, leaving the hall seeming slightly lost and diminished on the left.

|

|

Federal Reserve Bank of China 500 Yuan of 1943. An inflation issue of this Japanese occupation puppet bank depicting the temple hall at left and Confucius at right. Japan occupied Beijing from 1937 to 1945.

|

Jì Mín Yín Háo - 濟民銀號 - Jinan Peoples Bank - 'The Public Savings Bank'. 100 coppers of 1928. A minor regional commercial issue for a bank possibly in Hubei. This example is probably a remainder as a similar note by this issuer has serial numbers which this lacks. Numerous 'small' commercial notes carry the image of the temple.

|

|

Left: A 'Hell Bank' note for 50 Yuan dated 1929. In this context 'hell' simply meant the afterlife. Later notes show a mythical temple or Hell Bank (possibly derived from an image of the Dacheng Hall of the Temple of Confucius at Qufu in Shandong (Shantung)), however here the Temple of Heaven (naturally enough) was used. Hell or heaven money was faux currency burnt at funerals or as offerings to the ancestors during festival periods. The vintage notes without English text are sometimes mistaken for small commercial currency as they share numerous similarities with such. The heavily handled appearance of a few examples may be an indication of occasional attempts to pass such notes as legitimate currency. Smith & Matravers (Chinese Banknotes, 1970) suggested that there could be as many as a million or more varieties of hell notes. |