|

January 2019

|

The Farmers Bank of China - 中國農民銀行

|

This bank was initially established on a limited scale as the Agricultural Bank of the Four Provinces in 1933, under an executive order of Chiang Kai-shek, who appointed Guo Waifeng as Director.

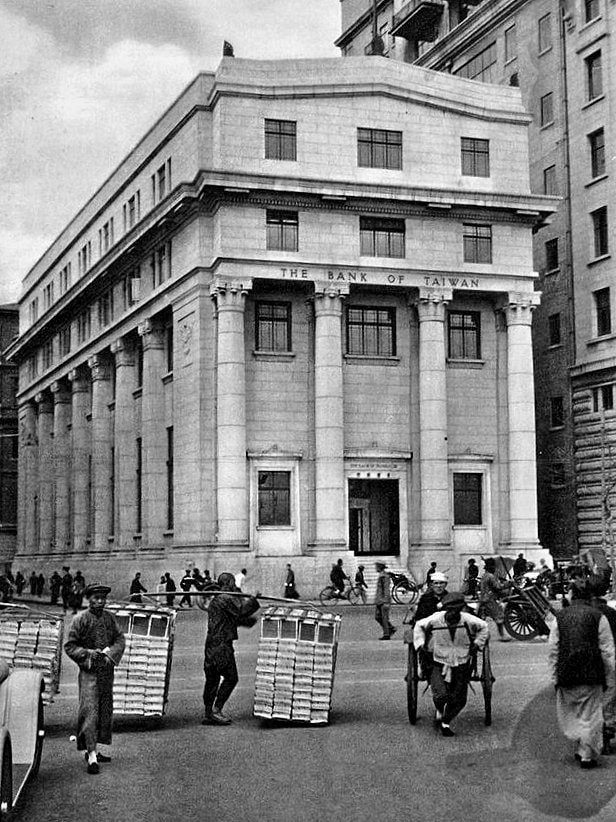

One of the principle motivations for founding this bank was the need to increase military funding due to the seemingly endless internal conflicts against the warlords, the Communists, and now the Japanese. Tensions arose between Chiang and his brother-in-law T.V. Soong, Minister of Finance; the military budget was being reigned in both by the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of China. This led Chiang to seek the establishment of a new bank as his solution to the funding problem. He was not by any means the first military leader in China to take such a route, though his predecessors were mostly engaged in outright theft, issuing essentially worthless currency out of insubstantial banks which literally in some cases disappeared overnight (a good example of this is the Bank of the Northwest established by the Warlord-General Feng Yu-hsiang). Right: The Bank of Taiwan on the Bund, Shanghai. This became an office (the headquarters?) of the Farmers Bank of China from 1945 to c1950. |

The ‘Four Provinces’ bank opened in April of 1933, without consultation to the Ministry of Finance, and with capital of 3 Million yuan, 2.25 of which came straight from Chiang Kai-shek. As intended, this enabled him to exercise complete control over the banks operations.

As there was an ever greater need for military funding during the progression of the civil war, Chiang requested that the bank operations be extended nationally, hence it was quickly re-established as the Farmers Bank of China (中國農民銀行) on April 1st 1935. The bank funded local landlords to return to their villages when they had been cleared of Communist forces, in order to establish the pawn shops and farming cooperatives which would help support his military expenditures. The bank was also heavily involved in the opium trade. Significant loans of 10s of millions of yuan were also made to the Nationalist army.

As there was an ever greater need for military funding during the progression of the civil war, Chiang requested that the bank operations be extended nationally, hence it was quickly re-established as the Farmers Bank of China (中國農民銀行) on April 1st 1935. The bank funded local landlords to return to their villages when they had been cleared of Communist forces, in order to establish the pawn shops and farming cooperatives which would help support his military expenditures. The bank was also heavily involved in the opium trade. Significant loans of 10s of millions of yuan were also made to the Nationalist army.

The headquarters of the bank were moved from Hankow (Hankou) to Shanghai in April 1937 (though ‘A History of Modern Shanghai Banking‘ states 1935), but the Shanghai Bankers Association refused the bank membership due to it’s close ties with Chiang. These ties however enabled the bank to become the 4th largest in China. By December of 1937, the Farmers Bank had 96 branches and sub-branches across 14 provinces. Soon after, it relocated again due to the war; to Chungking until 1945.

The bank issued its own currency from 1933 - and from 1935 as the Farmers Bank - until 1942 when currency issue was restricted to the Central Bank of China. However the bank issued savings certificates and cashiers cheques which looked and seemed to have sometimes circulated as currency, from 1943-1945.

The bank was abolished by the communist government within mainland China in 1950-51 due to it's close ties with Chiang Kai Shek, and re-organised as the Agricultural Co-operative Bank in 1951. The bank continued to operate on Taiwan (ROC) until 2006.

The bank issued its own currency from 1933 - and from 1935 as the Farmers Bank - until 1942 when currency issue was restricted to the Central Bank of China. However the bank issued savings certificates and cashiers cheques which looked and seemed to have sometimes circulated as currency, from 1943-1945.

The bank was abolished by the communist government within mainland China in 1950-51 due to it's close ties with Chiang Kai Shek, and re-organised as the Agricultural Co-operative Bank in 1951. The bank continued to operate on Taiwan (ROC) until 2006.

The Currency

Banknote issuance was (post Fabi-reforms of 1935) formally approved after January 1936 though possibly not concretely established until February 1937. The bank was ordered to concentrate banknote issuance in mainly rural areas.

This article is not a comprehensive catalogue of the currency of the Farmers Bank but will focus upon the often lesser known features of these notes. At some point it may be expanded to cover all issues.

This article is not a comprehensive catalogue of the currency of the Farmers Bank but will focus upon the often lesser known features of these notes. At some point it may be expanded to cover all issues.

|

The initial issue of the Farmers Bank utilised designs adapted from that of the Four Provinces series of 1934. The vignettes depict generic agricultural scenes. The denominations consist of two different 10 cents and three different 20 cents notes plus both 1 yuan notes shown here, of which there are branch varieties. Right: The Agricultural Bank of the Four Provinces 1 yuan of 1934, Hangchow (Hangzhou) branch. Printed by the Ta Yeh (Dah Yip) Co, as are the later matching Farmers bank issues. Below: right: The Farmers Bank of China 1 yuan of '1934' (1935) - a direct adaptation of the Four Provinces note. Some issues specify the issuing branch though this example does not. Known branch issues include: Foochow, Chengchow, Changsha, Lanchow, and Sian. Below: left: a much scarcer and more obscure Farmers Bank of China 1934 (c1935?) issue in blue. The Chinese and English name of Szechuan (Sichuan) Province has been blacked out and replaced with Shanghai (in Chinese only). There is a further unknown sequence of four characters obscured by stars which do not appear on the other notes. |

The 1935 De La Rue Series - 年四十二國民華中

|

The '1935' series banknotes were most likely not issued until 1936 onwards. Some examples of this series carry Tibetan text overprinted in the left and right hand cartouches on the front of the notes; this has been observed for the 5 and 10 yuan. The Tibetan text is apparently the denomination. Examples are also encountered with a variety of numerical control overprints, as shown to the left, in at least three different styles. Printers models including alternate designs, colour trials (with one exception, listed below) and similar items do not appear to be extant for this series. Such materials may exist in an archive or private collection or they may have been destroyed by the bombing of the Bunhill Row factory in 1940, during the Blitz. That said, such items do survive from the period for other banknote series. Various specimens are known. |

|

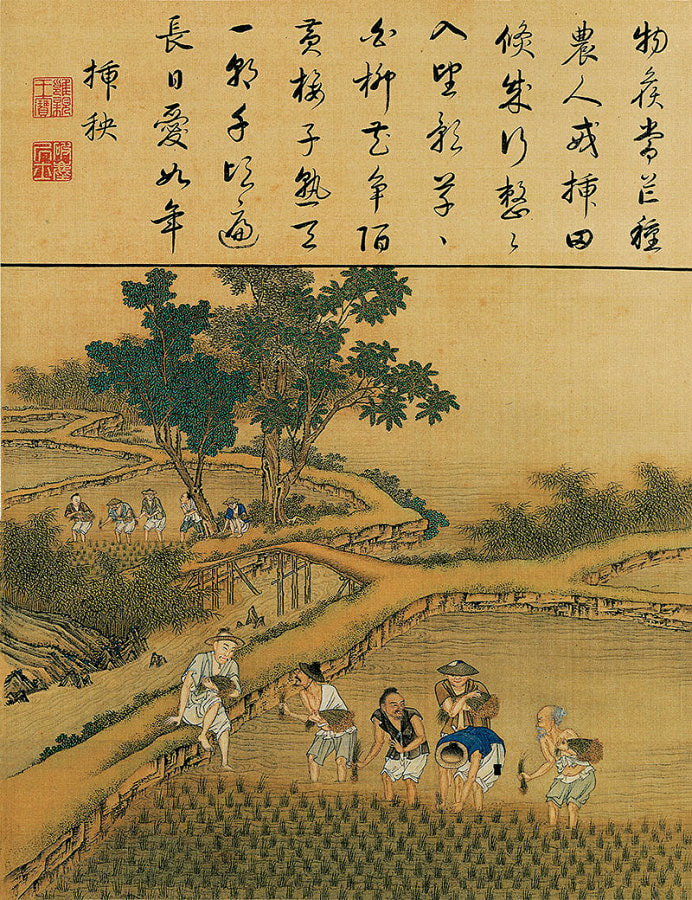

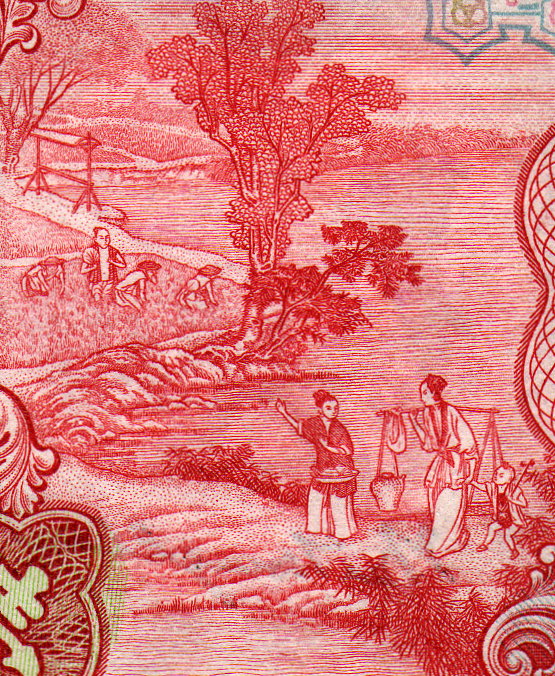

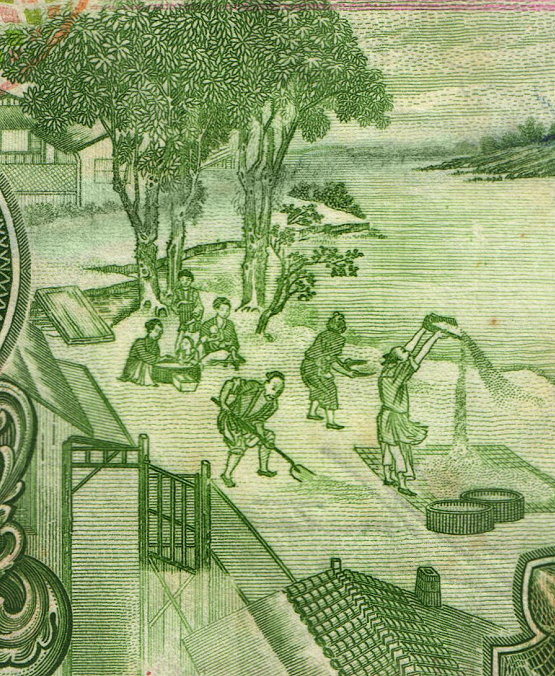

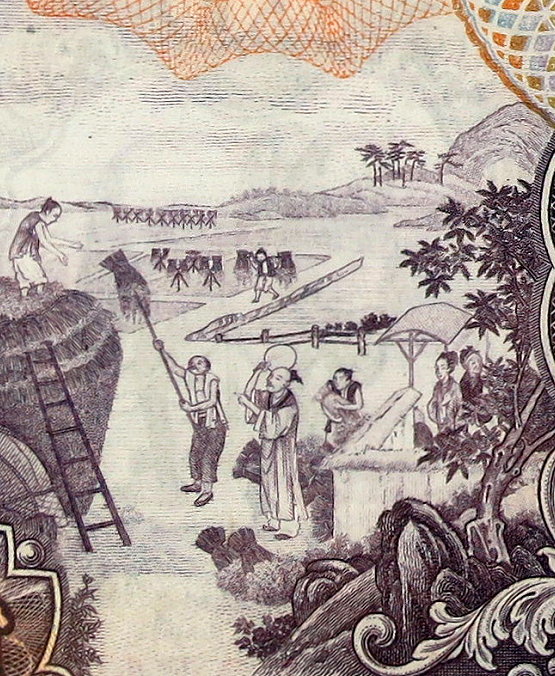

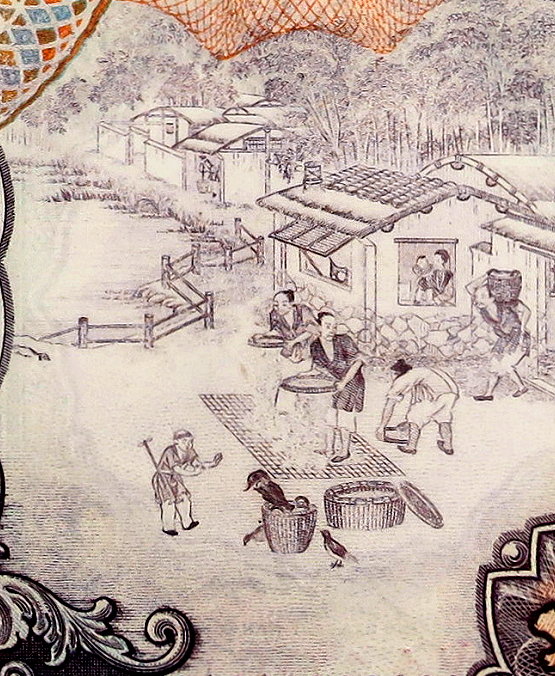

The scenes on the front of these banknotes are based on images from a 17th century recreation of the Song dynasty work 'Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture' 御製耕織圖 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' (胤禛耕织图册·收刈). "The original Gengzhi Tu was compiled by Lou Shou during the Song Dynasty, around 1132, and contained 45 illustrations accompanied by poems. The 1696 edition by the court painter Jiao Bingzhen is known as the Yuzhi (Imperial) Gengzhi Tu to refer to the Emperor's commission of it, and shows a strong European influence." Various versions both hand produced or printed exist, however that in the collections of the Beijing Palace Museum (The Forbidden City) appears to be the one directly used to produce these illustrations, presumably via photographs. Another painted version copied by Leng Mei, a Kangxi court painter, is now in the Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan. (see Chinese Graphic Design in the 20th Century by S Minick and J Ping, p15. Thames and Hudson 2009) |

|

Above and right: The 1935 series were designed to carry the usual official seals (usually square red seals) on the front - however, presumably due to the initial problems with the Ministry of Finance, these seals were never applied, even to later issues of the notes, presumably so as to prevent confusion. Above: I have emphasised the intended positions for clarity. The 5 Yuan has the most obvious example; the faded out lower half of the gate at the right.

Right: a mock up of how the notes were presumably intended to look (also see below). |

An overlooked design element are the empty cartouches which appear in the left and right hand borders of the front, and the spacing at the lower centre of the rear of the note, beneath the denomination. These were of course intended to bear the names of various issuing bank branches, Chinese and Romanized respectively, as had been the case with the first note issues by the bank. This however was not taken up, most likely due to the progression of the civil war, and growing tensions with Japan, leading to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Towns and cities, and hence bank branches, came in and out of Nationalist control which would lead to problems if the currency was issued as redeemable only at specified branches. Some notes are known with the empty cartouches utilised to carry overprinted control numbers.

The 1941 De La Rue issues would continue to display these seemingly redundant components, and the only branch name to appear on any Farmers Bank notes after the 1934 series, would be that for Chungking (Chongqing); overprinted in Chinese only on the front of the 1941 50 and 100 Yuan issues by the American Banknote Company.

The 1941 De La Rue issues would continue to display these seemingly redundant components, and the only branch name to appear on any Farmers Bank notes after the 1934 series, would be that for Chungking (Chongqing); overprinted in Chinese only on the front of the 1941 50 and 100 Yuan issues by the American Banknote Company.

|

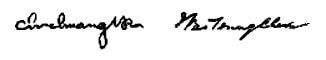

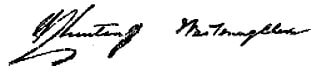

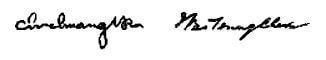

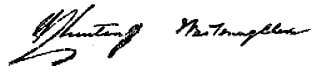

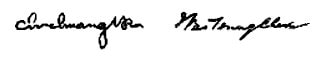

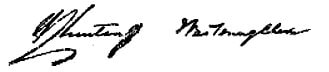

1 yuan (National Currency)

Red, with multicolour underprint. (front) ‘classical’ agricultural scenes originally from the Southern Song Dynasty 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' (Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture/Tilling and Weaving). (back) The Clock (bell) Tower of Fayu Temple, Putuo Mountain, Zhoushan, Chekiang (Zhejiang). A vignette of horned sheep at the right. - Further details below. Watermark: a cow's head Printer: Thomas De La Rue & Company Ltd, London. 德纳罗印钞公司 Type 1 (Krause SCWPM P 457a (i), Smith & Matravers C290-30a). Signatures: Xu Jizhuang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 2 (Krause SCWPM P 457a (ii), Smith & Matravers C290-30b). Shown; above right Signatures: Ye Zuotang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 3 Specimen Right: this item sold via the Yangming Auction Company is something of a mystery. It is not a standard specimen, lacking all of the normal markings to indicate such. All of the underprinting is missing, and it carries an unusual double set of serials. It may be an internal proof/specimen used within the printers, De La Rue. It is presumably the entry marked as 457A in the SCWPM. |

|

Right: a specimen/proof which appeared recently at a Spink auction, along with other Farmers Bank and Central Bank of China proofs by De La Rue. The serial number prefix and colour reveal it to be a test printing in the development of the 1941 series version of this note, which replaces the agricultural scenes with a portrait of Dr Sun Yat-sen (see Section 3). |

The back and front vignettes of the 1 yuan:

|

The back:

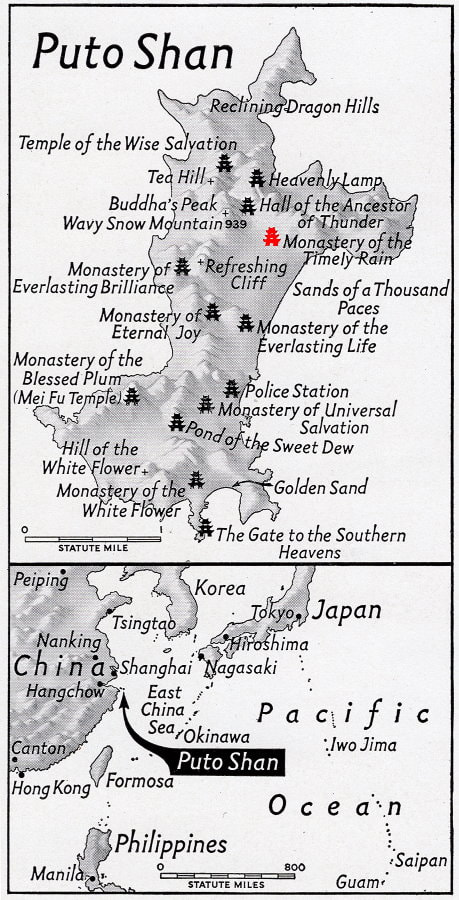

Putuo (Putu/Pootoo/Putuoshan), an island, is one of the four sacred mountains of Chinese Buddhism, considered the seat of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin). The Fayu temple was established in 1580 and remains one of over 30 temples on the island. After 1699, the temple was renamed the "Dharma Rain Temple", or "Fayu Temple". (right) it is marked on this c1946 map as the "Monastery of the Timely Rain". The bell tower (below) seems to be no longer standing - in fact there is no other known confirmation of it's existence beyond this one 19th century photograph that was clearly taken at least a decade before that used for the vignette. |

The front:

Below: as mentioned above; the Qing/Song dynasty scenes from the 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' which are the basis for the left and right vignettes on the front of the 1 Yuan.

|

5 yuan (National Currency)

Green, with multicolour underprint. (front) ‘classical’ agricultural scenes originally from the Southern Song Dynasty 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' (Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture/Tilling and Weaving). (back) The Fuling tomb, of the Manchu Tombs at Mukden (Shenyang), formerly Manchuria. A vignette of a cow at right. - Further details below. Watermark: a cow's head Printer: Thomas De La Rue & Company Ltd, London. 德纳罗印钞公司 Type 1 (Krause SCWPM P 458a (i), Smith & Matravers C290-31a). Signatures: Xu Jizhuang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 2 (Krause SCWPM P 458a (ii), Smith & Matravers C290-31b). Shown; above right Signatures: Ye Zuotang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 3 Specimen Right: a well worn 5 yuan with overprints giving the denomination in Tibetan at left and right. 10 yuan examples are also known. |

The back and front vignettes of the 5 yuan:

|

The back:

Long'en Hall of the Peiling (Fuling) Mausoleum at Mukden (Fengtien, Shenyang). Located in the eastern suburb of Shenyang, Liaoning Province, Fuling Tomb (East Tomb) is the mausoleum of Nurhachi (1559-1626), the founder of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and his empress, Xiaocigao. The tomb was begun in 1629 and finished in 1651. |

The front:

Below: as mentioned in the introduction above; the Qing/Song dynasty scenes from the 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' which are the basis for the left and right vignettes on the front of the 5 yuan.

|

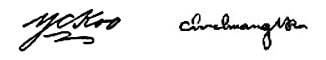

10 yuan (National Currency)

Purple-black, with multicolour underprint. (front) ‘classical’ agricultural scenes originally from the Southern Song Dynasty 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' (Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture/Tilling and Weaving). (back) The Zhaoling tomb, Manchu Tombs at Mukden (Shenyang), Manchuria, & horse. - Further details below. Watermark: a cow's head Printer: Thomas De La Rue & Company Ltd, London. 德纳罗印钞公司 Type 1 (Krause SCWPM P 459a (i), Smith & Matravers C290-32a). Signatures: Xu Jizhuang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 2 (Krause SCWPM P 459a (ii), Smith & Matravers C290-32b). Signatures: Ye Zuotang (General Manager) - Chen Huaizhong (Assistant Gen. Manager) Type 3 (Krause SCWPM P 459a (iii), Smith & Matravers C290-32c). Shown; above right Signatures (engraved): Gu Yiqun (Acting General Manager) - Xu Jizhuang (Assistant Gen. Manager) Right: an example of the first issue with control overprints, in this case '101'. The SCWPM designates these as 'b' (in this case P 459b) in its 1935 series listings. |

Type 3 P 459a (iii) as noted above carries the signature of Y C Koo (Gu Yiqun) as 'acting general manager.' This unusual designation (issues of the Farmers Bank being the only instance of this appearing on Chinese currency as far as I'm aware) means that he held the post due to the sudden absence or incapacity of the General Manager. In this case it was due to the death of Ye Zuotang in 1940 (General Manager since 1937). Gu Yiqun was the Vice Minister of Finance and later assumed the role officially (General Manager from 23rd October 1941 - October 1945).

This example is the third and final issue of these series of 1935 De La Rue notes and the only one of the type to carry the 'Y C Koo' signature. The 1 and 5 Yuan of 1935 the series was replaced with P 474 and P 475 of 1941, which carry this signature.

Another noteworthy point is the reappearance of Xu Jizhuang (General Manager until his removal in 1937) as 'Assistant General Manager'.

This example is the third and final issue of these series of 1935 De La Rue notes and the only one of the type to carry the 'Y C Koo' signature. The 1 and 5 Yuan of 1935 the series was replaced with P 474 and P 475 of 1941, which carry this signature.

Another noteworthy point is the reappearance of Xu Jizhuang (General Manager until his removal in 1937) as 'Assistant General Manager'.

The back and front vignettes of the 10 yuan:

|

The back:

The Zhaoling Mausoleum at Mukden (Fengtien, Shenyang). Located within Beiling Park, in the Huanggu District of northern Mukden (Shenyang), Liaoning province. Also known as the Beiling mausoleum, it is the tomb of the second Qing emperor, Hong Taiji, and his empress Xiaoduanwen Borjite. The tomb complex took eight years (between 1643 and 1651) to build and is the largest of the three at Shenyang. Right and lower-right: c1920s photo and postcard of the site Below: an aerial view of the tomb complex c1990s. |

The front:

Below: as mentioned in the introduction above; the Qing/Song dynasty scenes from the 'Yuzhi gengzhi tu' which are the basis for the left and right vignettes on the front of the 10 yuan.

The motives for the choice of imagery on the 1935 series?

The choice of imagery for the face of the notes is logical enough; classical scenes of agriculture for a Farmers Bank, reproduced from an historically and culturally significant manuscript. The reverse-right side images of animals again so.

The motives behind the central vignette of the reverse of each note however are not as immediately clear.

The 1 yuan depicts a bell tower from a temple complex on Putuo Island. Putuo is one of China's four sacred mountains; a culturally significant site; and the temple in question was known as the "Monastery of the Timely Rain" (rain of course being vital to agriculture) during the period. All of which most likely explains the 1 Yuan.

With the 5 and 10 yuan however it is far less clear: buildings from two Imperial Manchu tomb complexes? There is no obvious connection with agriculture, so the motives are more likely purely cultural and political:

Mukden (Shenyang) was briefly the capital of the Manchu Qing Dynasty until the Manchus conquered the remainder of China and moved the capital to Beijing. Mukden however remained important as a secondary capital, and the early Manchu tombs were once among the most famous monuments in China. At the end of the dynasty, shortly before the revolution, it became the capital of Fengtian Province.

From 1905 onwards, the Japanese increased their influence in the city and used it as a base of operations to persue their interests in North Eastern China. Warlord General Zhang Zuolin ruled Manchuria as the region was then known, with Mukden as his capital, and was an ally of the Japanese. He was also head of the national Beiyang Republican Government at Peking (Beijing) from June 1927. Following his defeat against Chiang Kai-shek in June 1928, he was killed by a bomb planted by the Japanese; despite being allied with them, the Japanese Kwantung Army was enraged at his failure to prevent Chiang Kai-shek from taking control of the Chinese government.

On September 18, 1931, a small quantity of dynamite was detonated close to a railway line near Mukden owned by the Japanese South Manchuria Railway Company, by Kwantung Army Lt. Kawamoto Suemori. The Imperial Japanese Army, accusing Chinese dissidents of the act, then used the 'false flag' explosion as a pretext to launch a full attack on Mukden, and captured the city the following morning. This tactic was later used again in 1937, at the 'Marco Polo' bridge near Peking, to justify taking that city and entering into open warfare with China.

After what became known as the Mukden Incident, the Japanese further invaded and occupied the rest of Northeast China, creating the puppet state of Manchukuo with the deposed Qing-Manchu emperor Aisin Gioro Puyi as the figurehead, in 1932. Puyi had wanted Mukden to become the capital - it was the former Manchu capital, and the historic palace - a smaller version of the Forbidden City - survives to this day. However he was overuled by the Japanese who established the capital at Hsingking (Changchun).

The well established significance of these monuments and their location within a Japanese occupied region of China is undoubtedly the motivation behind what initially seems to be an odd choice of subject for the paper money of an agricultural bank established 1000 miles away. But then this was a Nationalist government bank established by Chiang Kai-shek. These images were possibly used as both a reminder and a claim to the lost region of China's northeast. And perhaps even a threat of sorts against the Manchu puppet ruler of Manchukuo, who had been proclaimed as emperor of the state in 1934?

The motives behind the central vignette of the reverse of each note however are not as immediately clear.

The 1 yuan depicts a bell tower from a temple complex on Putuo Island. Putuo is one of China's four sacred mountains; a culturally significant site; and the temple in question was known as the "Monastery of the Timely Rain" (rain of course being vital to agriculture) during the period. All of which most likely explains the 1 Yuan.

With the 5 and 10 yuan however it is far less clear: buildings from two Imperial Manchu tomb complexes? There is no obvious connection with agriculture, so the motives are more likely purely cultural and political:

Mukden (Shenyang) was briefly the capital of the Manchu Qing Dynasty until the Manchus conquered the remainder of China and moved the capital to Beijing. Mukden however remained important as a secondary capital, and the early Manchu tombs were once among the most famous monuments in China. At the end of the dynasty, shortly before the revolution, it became the capital of Fengtian Province.

From 1905 onwards, the Japanese increased their influence in the city and used it as a base of operations to persue their interests in North Eastern China. Warlord General Zhang Zuolin ruled Manchuria as the region was then known, with Mukden as his capital, and was an ally of the Japanese. He was also head of the national Beiyang Republican Government at Peking (Beijing) from June 1927. Following his defeat against Chiang Kai-shek in June 1928, he was killed by a bomb planted by the Japanese; despite being allied with them, the Japanese Kwantung Army was enraged at his failure to prevent Chiang Kai-shek from taking control of the Chinese government.

On September 18, 1931, a small quantity of dynamite was detonated close to a railway line near Mukden owned by the Japanese South Manchuria Railway Company, by Kwantung Army Lt. Kawamoto Suemori. The Imperial Japanese Army, accusing Chinese dissidents of the act, then used the 'false flag' explosion as a pretext to launch a full attack on Mukden, and captured the city the following morning. This tactic was later used again in 1937, at the 'Marco Polo' bridge near Peking, to justify taking that city and entering into open warfare with China.

After what became known as the Mukden Incident, the Japanese further invaded and occupied the rest of Northeast China, creating the puppet state of Manchukuo with the deposed Qing-Manchu emperor Aisin Gioro Puyi as the figurehead, in 1932. Puyi had wanted Mukden to become the capital - it was the former Manchu capital, and the historic palace - a smaller version of the Forbidden City - survives to this day. However he was overuled by the Japanese who established the capital at Hsingking (Changchun).

The well established significance of these monuments and their location within a Japanese occupied region of China is undoubtedly the motivation behind what initially seems to be an odd choice of subject for the paper money of an agricultural bank established 1000 miles away. But then this was a Nationalist government bank established by Chiang Kai-shek. These images were possibly used as both a reminder and a claim to the lost region of China's northeast. And perhaps even a threat of sorts against the Manchu puppet ruler of Manchukuo, who had been proclaimed as emperor of the state in 1934?